Arracacha (Aracacia xanthorrhiza)

| I am no longer actively breeding or growing arracacha. There are more crops in the growing guide that I have stopped growing than that I continue to grow. There are many reasons why I stop growing a plant. Often the available genetic diversity isn’t sufficient, the crop does not perform well in my climate, or I just find that I don’t enjoy or make much progress breeding it. Sometimes I come back to a plant later, but you should assume that this crop will not be offered in the store in the foreseeable future. |

Overview

- Arracacha is a root crop native to the Andes and introduced to Brazil, where it is known as mandioquinha-salsa, and parts of the Caribbean, where it is known as apio.

- This crop is challenging to grow in the Pacific Northwest and coastal California and very difficult in the most of the rest of the US.

- Plants produce a cluster of carrot-like roots that can each weigh more than two pounds.

- Yields can reach more than six pounds per plant, but that is unlikely outdoors in the US.

- The roots are are typically white to yellow in color, sometimes with a purple ring in the flesh.

- The roots are eaten cooked and are like combination of potato and carrot, very soft and aromatic.

- The leaves and stems (petioles) of arracacha are also edible and are somewhat similar to celery leaf.

- Arracacha reaches maturity in about 13 months and is not frost hardy, so it is hard to grow to full size in the US.

- Smaller carrot-sized roots can be grown in about seven months.

- The crop is propagated by planting offsets. True seeds are rare and used only for breeding.

This guide provides information about growing arracacha in North America, and particularly the Pacific Northwest, which is the only place that I have experience growing it. Much of the information will apply anywhere, but considerations about the timing of planting and harvesting, climate, photoperiod, and pests and diseases will vary considerably by location.

About Arracacha

Description

Arracacha (Aracacia xanthorrhiza), pronounced ar-ah-CAH-cha, is a member of the family Apiaceae, a relative of plants like carrot, parsnip, celery, and parsley (and, in this book, root chervil and skirret). It is sometimes called Peruvian carrot or Peruvian parsnip in English, but the perilous nature of these names should be obvious. Let’s stick to calling it arracacha.

In form and flavor, it is something like a cross between a carrot and celery. The storage roots are like a cluster of up to ten very large carrots with the aromatic flavor of celery. The stems and leaves are similar to those of celery as well, although the stems are not nearly as thick as those of celery.

The plant can grow as tall as three feet (91 cm) and about as broad, although typically only about two-thirds that size in plants that are harvested after their first year. Roots can be white or yellow, sometimes with purple streaking and some interior color. All parts of the plant are edible, even the central rootstock and cormels, although the storage roots are the most commonly consumed part. Arracacha is a perennial plant; the top growth dies back over the winter, but the plant will return year after year as long as the soil doesn’t freeze.

Its native territory stretches from Venezuela to Bolivia, but it is most well known in the northern part of its range: Colombia and Venezuela. It is grown as high as 10,500 feet (3200 m), although mostly much lower than that (NRC 1989).

There may be as many as 50 varieties in the Andes. Diversity is greatest in Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. Unlike many of the Andean root crops, arracacha is popular and appears to be at no risk of disappearing, although varieties containing valuable diversity in the southern part of its range (Peru, Bolivia, and especially Chile) may be at risk.

Two varieties appear to be commonly available outside the Andes: the Puerto Rican clone introduced to North America by Sacred Succulents and a variety of unknown origin introduced first to Australia by Zaytuna Farm (Joel 2013). There are also two wild collections in circulation, but they won’t be very useful unless the cultivars can be induced to flower, allowing them to be crossed. As of 2018, I am working with a seed-grown population of domesticated arracacha that shows a lot of phenotypic diversity, so hopefully that will eventually make crosses possible with the existing varieties. That would improve the prospects for arracacha breeding in this country significantly.

In addition to the domesticated varieties, wild arracacha still grows in many places in the Andes. Some wild accessions grow at elevations where frosts are common and might be useful for introducing greater cold tolerance to the domesticated varieties. Wild collections appear to set seed much more readily than the domesticates. Unfortunately, they have small, hard, astringent roots and are basically inedible. There are both biennial (monocarpic) and perennial (polycarpic) populations of wild arracacha. The perennial wild arracachas are more closely related to domesticated arracacha than the biennial populations (Danderson 2018). Morillo (2017) found that cultivars formed two groups, one aligned closely with wild perennial accessions and another that appeared to have introgressed genetics from wild biennial populations. These two groups may have important differences in traits.

History

Arracacha likely originated as a domesticated crop in Ecuador (Hermann 1997). It is one of the more successful Andean roots; it is now widely cultivated outside the Andes, ranging from Brazil in the south to Cuba and Puerto Rico in the north. Arracacha is a hispanicization of racacha, one of the native names for the crop.

Arracacha was introduced to Puerto Rico in 1910 and has been grown there in the higher elevations ever since (NRC 1989). Most arracacha is grown in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela. More arracacha is now grown in Brazil, where it has been grown since the early 1900s, than in the Andes. Brazil has done a lot of breeding work with arracacha and now has relatively quick cropping varieties that are grown in warm temperate lowland areas (Hermann 1997). In Brazil, arracacha is known as batata baroa or mandioquinha salsa, literally “baron’s potato” and “cassava parsley”.

Unlike many of the Andean roots, wild forms of arracacha still grow in the Andes. These undomesticated varieties contain strongly astringent substances and are said to be basically inedible, but they could be useful for breeding.

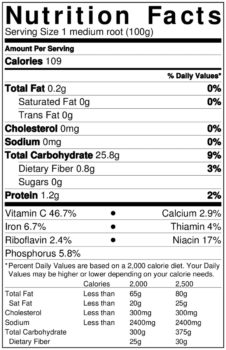

Nutrition

Arracacha is a starchy root with little protein or fiber. It is a high energy, highly digestible food that is also high in vitamin C. It is otherwise fairly low in vitamins and minerals.

Arracacha is probably not the healthiest of the Andean root crops. Of course, the objectives of subsistence agriculture and modern agriculture are different: calories are highly important when they are difficult to obtain and, with a 6.6 pound (3 kg) maximum yield, a single arracacha plant can provide as many as 3270 calories.

Cooking and Eating

Arracacha can be prepared in any way that carrots and potatoes can be prepared. They are baked, boiled, fried, and added to soups and stews. They are processed and used in baking, either as pulps or processed down to flour or starch (NRC 1989).

Arracacha roots are only eaten cooked; they are simply too hard to eat raw. The cooked root is soft, slightly sticky, extremely dense, and has a flavor something like a combination of carrot, potato, and celery.

The stems and leaves are also edible and taste similar to celery. I think that they accompany fish particularly well. The strongly flavored older leaves can make a good addition to soup stock. Harvesting too many is probably not a good idea if you are hoping for good sized roots, since the plant already struggles to produce those in a short growing season. I always reserve a few plants for harvesting greens and leave the rest alone.

Apparently, the aroma of arracacha is not as delightful to some as it is to others (Hermann 1997). It is a love it or hate it odor, similarly to cilantro. I can’t imagine anyone disliking arracacha, but I love cilantro too.

Cultivation

Climate Tolerance

In its native range, arracacha is grown from the lower, subtropical elevations of the Andes, all the way up to 10,500 feet (3200 m), where the climate is cool and temperate. This is a Goldilocks plant, that occupies a niche fairly unique in tropical highlands, without extremes of cold or heat. Most lowland climates that are frost-free also get too hot for too long in the summer.

The aerial plant is killed by frost, but it requires a very long growing season, up to thirteen months. Therefore, to produce a good crop in North America, extraordinary measures are necessary. Growing in a tunnel for season extension will help in many places. I grow outdoors, but start the plants in pots in February. They are transplanted to the field at the end of March and harvested in early December or following frost, should it arrive earlier.

I have found that plants will survive overnight freezes down to about 20 degrees F, particularly if mulched, which means that they will survive most winters here in the ground.

Although it will tolerate relatively warm weather for an Andean crop, arracacha seems to like temperatures in the mid 60s to mid 70s F (15 to 25 C) best. It suffers in prolonged temperatures above 90° F (32 C) and the roots often suffer damage from bacteria in warm soils, which has prevented large scale cultivation in subtropical areas of the US. Below 50° F, arracacha grows so slowly that it requires two full growing seasons to produce worthwhile storage roots. Arracacha can probably be grown as an annual in USDA zones 8b and warmer, although full yields are definitely not guaranteed.

The crop requires moderate water. It is tolerant to drought, but drought may force the plant into a reproductive mode, ruining the storage root yield. Should this happen to you, there is no reason to be disappointed; arracacha seed is very difficult to obtain. If you don’t have a use for it, please get in touch!

Arracacha is reasonably shade tolerant; it probably evolved as an understory plant. That said, you need every scrap of sunlight you can get to produce a good yield in North America, so grow it in full sun if you plan to eat the roots.

Arracacha can be grown in the Pacific Northwest with some work, such as starting plants indoors and protecting them from frost toward the end of the growing season. It should perform reasonably well in coastal California, parts of Florida, and probably the Gulf coast, where it doesn’t get too hot. A previous attempt at commercial cultivation in Florida was unsuccessful, but smaller scale growing with closer attention paid to microclimate might be possible. Any climate that is frost free without scorching summer temperatures is probably worth a try.

Photoperiod

Photoperiodism of arracacha is not well studied and some sources suggest that it may form storage roots most quickly under short day conditions. The varieties available in the United States appear to be day neutral as far as I can tell, although I don’t have a lot of leeway in timing its growing period, so I might not be able to detect photoperiod differences.

Soil Requirements

Arracacha is not particularly demanding of soil fertility, as it is often grown following a potato crop without further amendment (Hermann 1997). It likes well drained, even sandy soils. It performs very well for us in 12 inches (30 cm) of sandy loam over clay. It will grow in moderately acidic to mildly basic soils.

Propagule Care

Arracacha offsets are cormels detached from the central rootstock. They are highly perishable in warm weather; they survive long enough to be mailed, but not much longer than that. For the longest storage life, don’t remove the cormels from the central rootstock. They can survive for months in cool conditions when left intact. Offsets should be potted for storage in slightly damp soil and stored at about 50° F (10 C). They will begin growing within a few weeks even at this temperature, so be prepared to care for house plants until conditions are suitable for transplant.

Planting

In row cropping, arracacha should be planted on roughly two foot (60 cm) centers in row, with three feet (90 cm) in between rows. This will leave just enough room to move between rows when the canopy closes.

Offsets should be pre-rooted. Although they are often started directly in the field in the Andes, shorter North American growing seasons demand more care. Pot the offset in damp soil, watering frequently enough to keep the soil moist but not soaking wet. The offset will root sufficiently for transplant to the field in about six weeks.

Harden off the potted offsets for several days and then transplant to the field at the same level they were planted in the pot.

Seeds

True seeds of arracacha should be soaked in room temperature water and then sown shallowly and kept at a temperature of 20C. According to Knudsen (2006), seeds begin to germinate in 8 to 10 days and germination continues for two months. In my first experience with arracacha seeds, I saw germination in 10 days and reached 50% germination in about five weeks. So far, I have obtained the best results planting the seeds about 1/3 to 1/2 inch deep and keeping them at temperatures of about 70F day and 55F night.

Management

In South America, any flower stalks are promptly removed in order to preserve root yield. Plants are slightly hilled if the storage roots become exposed, as they are extremely vulnerable to pests. Otherwise, the plants require little specialized care.

Companion Planting

I have no experience companion planting with arracacha. Given its long growing season, it would probably pair well with something shallow rooted and undemanding like annual herbs or leafy greens.

Growing as a Perennial

Growing arracacha as a perennial in most of North America will be a technical challenge. It is not feasible where the ground freezes even a small amount; the root is easily damaged by freezing. In marginal climates, you can heap mulch over the roots to protect them. In frost free climates, it can be left in the ground for more than one year, which may increase yields, although frost free climates are usually warm enough that the plants may not need additional time to form a good yield. There is one significant problem with growing arracacha for more than one year: the older roots develop a fibrous, inedible core. So, while an arracacha plant will survive indefinitely in a favorable climate. the roots will become less edible as it gets older.

Container Growing

Arracacha is said to produce little to no storage roots when grown in containers (Hermann 1997). This is unfortunate, since container growing would be one way to extend the growing season. Obviously container size must play some role, but this suggests that containers must be large and perhaps that soil temperature must be kept fairly cool.

Harvest

Arracacha requires roughly 10 to 13 months to reach maturity (NRC 1989). This unfortunate feature makes it difficult to get a good crop in most of North America. The plant can be harvested in as little as six months, providing a small yield of carrot like roots, but the total yield is usually less than 10% of what can be achieved in a full growing season. Individual roots may weigh as much as 2.2 pounds (1 kg), although they are generally smaller (Hermann 1997). With a full growing season, yields may be as high as 6.6 pounds (3 kg) per plant (NRC 1989). For the first few years that I grew arracacha, I didn’t achieve even half a pound (227 g). In 2018, I harvested a plant that produced 5.2 pounds of roots in 10 months from transplant. It was well above average, but I think that there is hope for getting reasonable yields in North America.

Historically, arracacha was grown in successive plantings and harvested in small batches as needed (Bristol 1988), a consequence of its perishability.

Offsets for the next growing season must be taken when the roots are harvested. They can be left attached to the root stock, but losses are greater than when they are immediately detached and rooted.

Storage

The optimum storage temperature for arracacha roots is 50° F (10 C), at which they can be stored for 28 days before loss of quality begins to become apparent (Ribeiro 2005). When stored significantly above or below this temperature, they quickly degrade in quality. Arracacha roots should probably not be washed, as this can reduce the already short storage life (Hermann 1997).

Storing crowns for replanting is a bit trickier. Arracacha has no dormancy, so the plants want to keep growing. I have had the best luck lifting plants after a light frost, once the tops have been killed. I then store the whole root ball under dry and dark conditions (or at least as dry as we can manage in this humid climate). The root balls dehydrate, but this seems to keep them from sprouting much. I then take offsets immediately before planting.

Preservation

As far as I know, arracacha is never canned, but is often dried. Many processed food products are made with arracacha pulp, starch, and flour.

Propagation

Arracacha is normally propagated vegetatively, with offsets. It can also be propagated by seed, but as a polyploid, it does not grow true, so seed is primarily useful for breeding.

Vegetative Propagation

Due to its polyploid nature, the only way to maintain varieties is to propagate them with offsets.

Offsets form from the central rootstock of the plant. These offsets can be detached and rooted. The simplest procedure is to plant them directly in damp soil, but experienced growers take more care in preparing the offsets. Trimming the offsets down to only two or three buds is said to reduce the size of the plant, but increase the size of the storage roots (Hermann 1997). For best results, the cuts should be allowed to heal for a day or two in a humid environment and the offsets should then be potted to root.

In my rather limited experience, wild arracacha does not produce substantial corms, but rather sprouts from small buds high on the storage roots. This makes it more difficult to divide and can also trick you into believing that the plant has died.

Sexual Propagation

Arracacha rarely flowers, although this characteristic differs between varieties. It appears that flowering is primarily triggered by environmental stress. Arracacha flowers with greater frequency in Brazil, where low temperatures and dry conditions may be responsible (Hermann 1997). Of course, the varieties grown in Brazil were bred there from seed, which also seems likely to have had some influence on the flowering frequency of the progeny. Morcillo (2017) suggested, although based on very limited information, that cultivars in the group that is more closely related to the biennial wild species may not flower as readily.

Flowering has been forced in some arracacha varieties by dehydrating mature crowns by 20 to 30 percent (Hermann 1997). I tried this many times without success, but it seems that I might not have been resolute enough. In 2018, I decided to withhold water from a group of plants in a greenhouse until they either flowered or died. Six of the eight plants died, but two survived and finally flowered almost a year later.

Arracacha is a tetraploid and progeny from self pollinated seeds demonstrate a considerable degree of variability. It is probably a facultative outbreeder, capable of self pollination, but with better seed set following cross pollination. This is the typical reproductive model in the Apiaceae. There may also be male sterile varieties; flowering was reported in the Zaytuna variety but the umbels eventually dried down without producing any seed. (Seed set is also impaired by high temperatures, which could have been the reason for failure to form seed in this case. At temperatures above 95 F (35C), the anthers are damaged and cannot produce pollen.) I later had the same experience with the Puerto Rico variety, despite favorable temperatures; the plants flowered abundantly but set no seed. Germinability of even fresh seed is quite low, 30% or less (Hermann 1997). This low rate of germination may be associated with self pollination. Knudsen (2006) found a germination rate of 37% in self pollinated seeds, but as much as 83% in crosses between domesticated and wild arracacha.

Problems

Pests

The usual enemies of Andean roots in North America apply here: slugs and voles. Take care to keep the storage roots covered with soil to defend against slug damage. Voles are trickier. They may prefer arracacha to any other root crop. I have been experimenting with surrounding arracacha with mashua (which voles do not like) and the early results look promising. It is probably just a matter of time until they learn though.

Although I haven’t observed them to be a particularly damaging pest, it seems that swallowtail butterfly caterpillars favor arracacha over most other plants that we grow here.

Diseases

Almost no information regarding diseases of arracacha in North America is available, given the minimal cultivation of this crop.

Bacteria and Fungi

In Brazil, the major disease is a rot caused by the bacterium Erwinia carotovora. The disease begins with small, water soaked depressions on the storage roots which rapidly expand and develop a foul odor (Romeiro 1988). This is a nearly ubiquitous pathogen of many crop plants and so is likely to present similar problems for arracacha cultivation in North America. It is a systemic infection that remains in the offsets to infect the next generation of clones (Hermann 1997).

Viruses

Arracacha is also affected by a number of viruses. Heirloom varieties available in the USA are infected with at least one Potyvirus. Very little information is available about the symptoms of most arracacha viruses. Viruses that are cross infectious with potato are usually those of the greatest concern, since they could be economically damaging. Arracacha virus A also infects potato, oca, and ulluco. Potato virus S infects arracacha and potato (De Souza 2017) as does potato black ringspot virus (Lizzaraga 1994). It has not been reported formally, but I have gotten positive results for Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus in arracacha plants that were showing leaf yellowing and necrotic spots. As always, be careful when introducing new varieties because one imported virus could become a problem for several of the Andean root crops.

| Virus | Genus | Present in USA | Frequency in Arracacha (USA) |

Seed Transmitted |

| Arracacha Virus 1 (AV1) | Closterovirus | No | Unknown/Not Detected | Unknown |

| Arracacha Virus A (AVA) | Nepovirus | No | Unknown/Not Detected | Possibly in arracacha |

| Arracacha Virus B (AVB) | Cheravirus | No | Unknown/Not Detected | Likely in arracacha |

| Arracacha Virus V (AVV) | Vitivirus | No | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in arracacha |

| Arracacha Virus Y (ArVY) / Arracacha Mottle Virus (AMoV) | Potyvirus | No | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in arracacha |

| Bidens Mosaic Virus (BiMV) | Potyvirus | No | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in arracacha |

| Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV) | Cucumovirus | Yes | Unknown/Not Detected | Possibly in arracacha |

| Potato Black Ringspot Virus (PBRSV) | Nepovirus | No | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in arracacha |

| Potato Virus S (PVS) | Carlavirus | Yes | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in arracacha |

| Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus (TSWV) | Tospovirus | Yes | Rare | Possibly in arracacha |

Defects

Arracacha plants appear to be quite regular in form and resilient to our climate conditions. I have observed no unusual problems during the growing season.

Crop Development

To begin with, there can really be only one goal: good root production in a shorter season. Almost all of North America is unsuitable for field cultivation of arracacha. While it can be kept alive on a small scale, it has no potential as an economically important crop at this point. In Brazil, they have brought the cropping time down to as little as seven months through a combination of breeding and cultural practices. We should be able to do that too. The job would be a lot easier if we could import plants or seeds from South America.

Relatives

As mentioned in the introduction, wild arracacha is found in the Andes and might be a source of valuable genetics for breeding, particularly for frost resistance. Both biennial and perennial populations exist and, presumably, the perennial accessions will be more useful for breeding with domesticated arracacha. Danderson (2018) performed a genetic analysis of the Arracacia clade and concluded that the closely related species A. equatorialis and A. andina should be moved under A. xanthorrhiza. This suggests that these populations might also be compatible and useful for breeding with arracacha, regardless of their ultimate taxonomic disposition. Alleles of the cultivars were found in wild species in the Andes, which indicates that there is probably ongoing exchange of genetics between the cultivars and wild species (Jean-Pierre 2006).

20 thoughts on “Arracacha (Aracacia xanthorrhiza)”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Where can we buy the seeds or plans to get this cultivation started? I live in Texas and have not been able to find ay…

I should have some starts available this fall. Arracacha is tricky to propagate in this climate and not always available.

Really interested please let me know as soon as I can place an order

Hi Bill – I sign up to your mailing list. I would like to be notified when you will have some starts available this fall. Thanks!

Hello Bill if you have any arracachia, seeds or bulb please let me know.

Hello, would love to buy some starters and try growing them in coastal Georgia.

Keep an eye out around November. Arracacha is hard to grow and unpredictable. I have it when there is a good crop, which is roughly every other year.

Please let me know when you have propagales. I had a successful one in coastal CA and the gopher ate. I am from Brazil and really miss it. t is the most delicious root.

Hi Bill.

Would you have some arracacha seeds, bulbs or plants available for sale?

I am very interested.

Please, let me know so I can place an order.

Thanks a lot.

I appreciate it.

Regards.

Leticia

I should have some starts available in the fall. If you want to be notified when they become available, please sign up for our mailing list.

Hi, Im from Brazil and we have work along 30 years with arracacha that we Plant and sell them with big companies.

May I can help EUA or some produce company to get success in there.

Hi Bill – I sign up to your mailing list. I would like to be notified when you will have some Arracacha (Aracacia xanthorrhiza) starts available this fall. Thanks!

I was introduced to Arracacha as apio in the central mountains of the Dominican Republic as a Peace Corps volunteer many moons ago. After subsisting in very good river and beans and cassava, green bananas and taro for the better part of two years, Arracacha tasted like food of the Gods. It’s taken me several years to figure out what it was as apio translates from Spanish as celery. I was pretty certain celery root was not the same thing. I spent twenty years propagating PNW native plants. Retired, I’d love to try my hand at Arracacia xanthorrhiza. Please add me to your list.

Hi Bill,

I am interested in buying arracacha. You mentioned that you will have some for sale in the fall. Please let me know. Thanks!

There will be no additional arracacha available this year. It was not a good year for that crop. Typically, I get a reasonably good crop about half the time, so hopefully 2021 will be better.

Thanks Bill. Wishing a better crop for 2021. I would like to be added to your waiting list.

Thanks

Hi Bill

I am also interested in getting some arracacha seeds or plant

Hi Bill – I sign up to your mailing list. I would like to be notified when you will have some Arracacha (Aracacia xanthorrhiza) starts available this fall. Thanks!

Hi Bill,

I would like to order Arracacha seeds or/and plants. Can you help me with that? I couldn’t figure out how to pre-order.

Thank you.

Hi from Germany and I am a professional gardener and graduated botanist/agriculturalist. As I understand spanish I have ordered new varieties of Arracacha from a breeding company called AGROSAVIA which is located in Colombia. Brazilians living in Germany will also try to bring some plant material for me.