Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum)

Overview

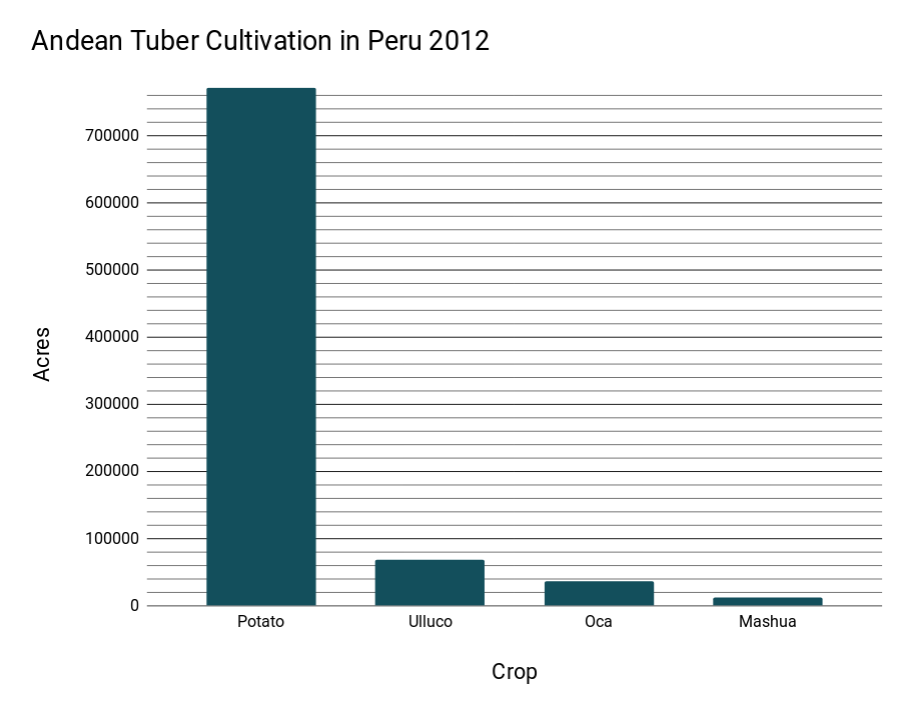

- Mashua is a tuber crop native to the Andes, where it was developed alongside the similar tuber crops potato, oca, and ulluco.

- This crop is easy to grow in the maritime Pacific Northwest and challenging to grow in the rest of the country.

- Mashua tubers range widely in size, from about three inches to more than thirteen inches.

- Yields can reach almost twenty pounds for plants grown on trellis, but are typically closer to five pounds without.

- Most varieties have white to yellow tubers, although red and purple varieties also exist.

- Cooked tubers are usually softer than potato and often taste cabbagey.

- Raw tubers have an odd combination of flavors that most people find unpleasant.

- Mashua leaves can be eaten and taste very similar to mustard greens.

- Mashua grows best where summer temperatures do not exceed 80 degrees.

- Tubers are produced during the short days of fall and are not ready for harvest until mid-November.

- The crop is propagated by planting tubers. True seeds are fairly easy to produce, but varieties do not grow true from seed.

This guide provides information about growing mashua in North America, and particularly the Pacific Northwest, which is the only place that I have experience growing it. Much of the information will apply anywhere, but considerations about the timing of planting and harvesting, climate, photoperiod, and pests and diseases will vary considerably by location.

About Mashua

Description

Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum), pronounced Mah-shwuh, is a member of the family Tropaeolaceae, along with the common garden nasturtium. it is also commonly known as tuberous nasturtium, añu, cubio, or papa amarga. The last is potentially confusing, as papa amarga (bitter potato) more commonly refers to the frost resistant potato species Solanum curtilobum and S. juzepczukii.

Mashua has long twining stems on which three to five lobed leaves form. In the fall (or mid to late summer for less common day neutral varieties), mashua forms trumpet shaped orange, orange and yellow, or occasionally red flowers.

It is an attractive plant and is probably better known as an ornamental than an edible outside of its native range. Plants grow up to at least 8 and possibly 12 feet (2.4 to 3.6 m) tall if given something to climb. They are fast growing in cool, wet weather and are generally able to out-compete and smother weeds.

Underground, the plant forms tubers that reach up to at least 13 inches (33 cm) in length, although more typically in the 3 to 8 inch (7.5 to 20 cm) range. the tubers have a shiny, waxy skin that cleans easily. Tubers cluster relatively closely under the base of the plant. Most mashua varieties have predominantly white tubers, although yellow, orange, red, and purple tubers are formed by some varieties. Given a long enough frost free autumn, plenty of water, and an overall cool climate, mashua can produce very high yields. We average 5 pounds (2.3 kg) per plant, but have seen as much as 16 pounds (7.25 kg) from a single plant. Warm climate yields are smaller, reaching perhaps two to three pounds (about 1 kg) per plant.

In addition to the domesticated mashua, there is a wild subspecies, Tropaeolum tuberosum subsp. silvestre. The northern limit of the subspecies is unknown, but it reaches from Peru south into Argentina (Bulacio 2012). Wild mashua’s thickened stolons can barely be categorized as tubers. They reach a maximum thickness of about half an inch (1 cm). They are more pungent and contain more forms of glucosinolates than the domesticated mashua. Although not particularly useful as an edible (other than for its leaves), I have found wild mashua useful for breeding with the domesticated varieties. I have produced several crosses between wild and domesticated mashua and the combination sometimes produces longer tubers that retain the bulk of the domesticated varieties (although, more often, the result is more similar to wild mashua).

Domesticated mashua is sometimes divided into two botanical varieties, var. lineamaculatum and var. piliferum (Hind 2010). The origin of these botanical varieties is unknown and they don’t appear to be particularly useful. The variety ‘Ken Aslet’ is generally associated with var. lineamaculatum and the variety ‘Blanca’ (once offered as ‘Sidney’ in the UK) with var. piliferum. Of these two terms, lineamaculatum is the easier to understand, since it refers to linear markings; piliferum, on the other hand, refers to hairiness and it is not obvious how this would describe any mashua variety.

Genetically, mashua is generally considered to be tetraploid (Gibbs 1978) and displays a fair degree of phenotypic variability in progeny from self pollinated seeds, similar to that seen in tetraploid potatoes (example here). There is also some evidence for diploid and triploid forms. It is probably an autopolyploid (Grau 2003), meaning that it resulted from a doubling of its ancestor’s genome, rather than hybridization with another species. Some varieties are probably more recent hybrids than others; for example, self pollinated seed of the variety Ken Aslet shows significantly more variability in form and color than is seen from the varieties Blanca or Bogota Market.

History

Evidence exists for ancient use of mashua, as much as 8000 years ago, probably with later domestication. The first archaelogical evidence of mashua use dates to roughly 700 to 1400 years ago (Grau 2003).

Mashua appears to have originated in the Titicaca basin of Peru and Bolivia and that is where its greatest diversity is still found. Although mashua remains a fairly diverse crop, it may still be in danger in the Andean region, where it has been particularly vulnerable to replacement by Old World crops (Leon 1964). Unlike some of the other crops that were once quite vulnerable, such as yacon and maca, mashua has yet to find a niche in global markets, although it has recently been proposed as a possible new “superfood” (Williams 2016). Information is not available over its entire range but, in Ecuador, loss of varieties amounting to 46.5% of its previously assessed genetic variability has occurred in recent decades (Tapia 2001).

The three common names for mashua in Peru, Bolivia, and Colombia, respectively mashua, isaño, and cubio, may indicate that the crop was widespread and well known prior to conquests by both the Incas and the Spanish (Grau 2003). Mashua is a name of Quechua origin and isaño of Aymara, both peoples of the central Andes. Cubio was the name used by the Muisca of the Colombian Andes (Torres 1992).

Mashua was introduced to Europe as early as 1827 (Hind 2010) and appears to have been grown continuously since then, but primarily on small scale as an ornamental.

Nutrition

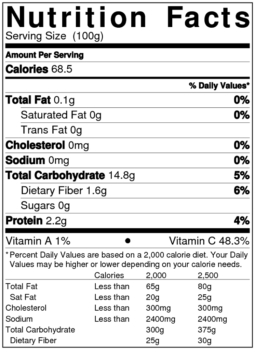

Mashua tubers are high in vitamin C and relatively high in protein for a root crop. The vitamin C content may vary significantly with variety and growing conditions. Some measurements of vitamin C content in mashua are as high as 120mg/100g (Torres 1992), which is more than twice as much as an orange and comparable to an equal weight of kale.

Mashua contains large amounts of glucosinolates (mustard oils) and, as a consequence, isothiocyanates. Isothiocyanates have antibiotic and insecticidal properties. They also appear to play a role in carcinogen detoxiification and/or promotion of apoptosis in pre-cancerous cells (Shapiro 1998). So, mashua consumption may be protective against some kinds of cancer. Freezing causes the breakdown of glucosinolates (as does heat, but less efficiently), which may explain why some traditional preparation methods involve freezing before cooking.

That all sounds pretty good. Maybe it really is a “super food!” on the other hand, those potentially cancer protective compounds may also have undesirable effects on male hormones or sperm function.

This has only been studied in rats, so effects on humans are a matter of speculation. Cardenas-Valencia (2008) reported on rats that were dosed with an extract prepared by first boiling and the freeze-drying the tubers. The dosage of the extract was corrected so that the amount of extract was equivalent to that found in a similar weight of raw tubers. Rats were dosed with 1 g mashua per 1 kg of body weight. In human terms, a 70 kg man would consume 70 g or 2.5 ounces of mashua. At the end of 42 days, they found slight reduction in sperm count and daily sperm production in the rats that ate mashua. The reduction was fairly consistent over the study period, not worsening with continued consumption. They found no difference in testosterone between the control and treatment groups. This would seem to refute the idea that mashua is an anaphrodesiac, but it may be best to limit consumption when trying to conceive since sperm production was slightly reduced.

In contrast, Johns (1982) found that feeding rats tubers that were only freeze-dried (rather than boiled first) produced as much as a 45% reduction in the levels of blood testosterone. Why did one study find such a large drop, while the other found none at all? With no replication of either study, it is hard to say. The one thing that stands out is that the tubers associated with the reduction in testosterone were uncooked. Most people don’t eat much raw mashua and I imagine that such a drop would definitely be noticed by anyone who consumed the plant as a staple crop. In the Johns study, the rats in the experimental group did not gain weight and showed a similar reduction in testosterone to rats in a control group that were also prevented from weight gain. The reason suggested in the paper is that the isothiocyanates in mashua were acting as a starvation factor, which in turn caused the drop in testosterone. Cooking breaks down isothiocyanates and I would guess that this moderates or eliminates the anti-metabolic or anti-nutritional factors present in raw mashua.

In contrast, Johns (1982) found that feeding rats tubers that were only freeze-dried (rather than boiled first) produced as much as a 45% reduction in the levels of blood testosterone. Why did one study find such a large drop, while the other found none at all? With no replication of either study, it is hard to say. The one thing that stands out is that the tubers associated with the reduction in testosterone were uncooked. Most people don’t eat much raw mashua and I imagine that such a drop would definitely be noticed by anyone who consumed the plant as a staple crop. In the Johns study, the rats in the experimental group did not gain weight and showed a similar reduction in testosterone to rats in a control group that were also prevented from weight gain. The reason suggested in the paper is that the isothiocyanates in mashua were acting as a starvation factor, which in turn caused the drop in testosterone. Cooking breaks down isothiocyanates and I would guess that this moderates or eliminates the anti-metabolic or anti-nutritional factors present in raw mashua.

There will need to be more study to get to the bottom of this matter. Nobody really knows what the long term effects of mashua consumption are in humans when consumed as part of a normal diet. Mashua has long been consumed in the Andes and is still commonly eaten in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, so its effects are probably not significant with normal consumption of cooked mashua if, in fact, they occur in humans at all. The continued existence of cultures that consume mashua would seem to attest to that. I don’t find the research particularly worrying, but, by all means, do your own research and consume mashua according to your appetite for risk.

Cooking and Eating

All parts of the plant can be eaten raw or cooked. The tubers are the most frequently consumed part. Although they can be eaten raw, this doesn’t appear to have ever been a common practice in the Andes. The raw flavor of mashua is not appealing to most people, or at least to those with western palates. The strong flavor is the result of glucosinolate and isothiocyanate content (Johns 1981). It is more common to eat mashua cooked, after which the flavor can range from strongly cabbagey and bitter to mild and sweet.

Basic preparation is similar to that for turnips, which have a similar water content and somewhat similar flavor. Most people will either boil or roast mashua until fork tender. We usually halve them, drizzle with a little oil, and roast at 350F. This can take 30 to 60 minutes depending on the size of the tubers. There is no need to peel mashua, although some people cut off the rose (distal) end of the tuber because the texture can be a little more fibrous. We usually don’t find it to be a problem. Like many roots and tubers, mashua is very nice cooked in the drippings under a roast.

Mashua is also sometimes consumed as a dessert, by boiling and then freezing the tubers. Having tried this, I only recommend it to the adventurous. Although not a traditional method of preparation, I think that it makes a pretty tasty pickle. The flowers have large nectaries and are sweet with a bit of aniseed flavor. Leaves are tasty as a salad green, with a bit of mustard-like spiciness, and the larger leaves can be used as a wrap, like grape leaves. There could be great potential in the development of mashua as a perennial leaf crop.

I think that mashua has a greater gap between its potential and the current state of the crop than any of the other Andean tubers. You can’t just toss some mashua on a plate and expect it to be delicious, but it can be in the right dish. Undercooked, it can be horrible, although there are a few people who even like it raw. Without special attention, fully cooked mashua tastes basically like turnip; not bad, but not terribly exciting. Still, its other attributes make it very appealing. Despite its current limitations, I’m really enthusiastic about mashua and think it has a bright future.

For cooks who like to explore in the kitchen, mashua is definitely worth some attention. While plain, boiled mashua is not the worlds most appealing dish, we keep stumbling over better ways to prepare it. As mentioned, mashua pickles are delicious and the adventurous fermenter could probably produce a very unique product. Mashua may benefit from lactofermentation, which seems to moderate the flavor (Smith 2010, Mar_25). I haven’t tried it yet as it didn’t look incredibly appealing.

Mashua can replace potato in Indian dishes and is often an improvement. It works well in strongly spiced dishes where it can’t get the upper hand. Cumin seems to have an almost magical balancing effect against its less appealing flavors. It is delicious roasted with meat and the fattier the meat, the better. These experiences make me optimistic that there are more delicious ways to cook with mashua just waiting to be discovered.

Cultivation

Climate Tolerance

Mashua is traditionally grown at elevations of 10,000 to 12,000 feet (3000 to 3700 m), where the average annual temperature is 52° F (11 C) (Grau 2003). It is poorly adapted to warm, dry conditions and so is best suited to maritime climates in North America. It thrives in climates with cool summer temperatures, where the high temperature rarely rises above 80° F (27 C). Where temperatures higher than 80° F continue for too many days, mashua will usually grow poorly. It needs consistent water and will benefit from a drip system in climates where rainfall is not regular.

The plant grows best in full sun in mild climates. Where temperatures frequently exceed 80° F, mashua will grow best in an area that has afternoon shade. I don’t know what the upper temperature limit is for mashua; some people grow it in climates that infrequently reach 100° F (38 C) in the summer and report daytime wilting, but recovery overnight. In climates with such high daytime temperatures, it is probably important that nighttime temperatures drop down into mashua’s preferred range. In dry climates, it is important to give mashua some wind protection, since dry winds will rob it of water faster than it can replace it.

The plant has some resistance to light frosts, but a hard frost will kill the foliage completely. Because tubers form in the fall, this makes it unsuitable for locations with frosts that occur earlier than the beginning of November. there is one exception: the variety Ken Aslet begins forming tubers in mid summer and can produce a reasonably good yield by the middle of October.

Mashua best fits USDA zone 9a (low temperature of 20 to 25° F (-7 to -4 C)). Approximately half of the tubers can be expected to survive a multiple day freeze at 25°F and approximately 20% at 20°. This can be improved by mulching heavily over the base of the plant before cold weather arrives.

Mashua will grow well in most of the Pacific Northwest, particularly the Puget sound region, the coast, the San Juans, the Gulf Islands, and southern Vancouver Island. It may struggle a bit in the warmer Willamette Valley in the height of summer. It is also grown in the lower elevations of the Appalachians and appears to perform reasonably well in the warmer microclimates around the Great Lakes in mild years.

Photoperiod

Mashua has photoperiod dependencies for both tuber formation and flowering. Most of the mashua varieties that i have grown have a critical day length of about 13 hours and begin to form tubers in early September. A few are closer to 12 hours and therefore don’t begin to form tubers until the end of September. Flowering begins a few weeks after tuber formation, in October for most varieties.

As noted previously, the variety Ken Aslet is an exception with a critical day length of about 14 hours. It is able to flower and form tubers in both spring and late summer in the Pacific Northwest, although they don’t have the opportunity to grow large in spring before the day length rises above 14 hours. They resume growing when the day length falls below that threshold again in summer.

Soil Requirements

Mashua thrives even in relatively poor soils, but loose, light soils benefit you at harvest time. A little complete organic fertilizer or compost should provide mashua sufficient nutrition. I have not done careful testing, but most of the Andean root crops respond poorly to rich fertilizers and we give them nothing but a top-dressing of well composed manure. Likewise, most Andean root crops prefer moderately acidic soils, although mashua appears to have a wide range of soil tolerance.

Propagule Care

Mashua tubers are particularly vulnerable to dehydration and will do better stored in soil than exposed to the air. Keep them in a dark, cool place and check on them from time to time. If you find that they are becoming soft, either put them in some barely damp soil or in the crisper of your refrigerator. A storage life of six months is about the best that you can expect.

Tubers stored at room temperature will begin to sprout by March. Sprouted tubers can wait to be planted for a couple of weeks, so it is not an emergency. It is best to store the tubers where they can get some light once they have sprouted; sprouts that grow in darkness will become spindly and fragile. It is a good idea to pot the tubers so that they don’t continue to expend their reserves. Put them in some barely damp soil with the tip of the sprout exposed and then transplant after the last frost. Long sprouts can be cut back, but should not be pulled from the tuber, as this often leads to rotting.

Planting

Plant mashua in the spring after risk of frost has passed. You don’t need to hurry with most varieties, because mashua won’t begin to form tubers until after the autumn equinox (about September 21). The exception is the variety Ken Aslet, which can form tubers earlier and may consequently benefit from early planting.

In row spacing of 30 inches (76 cm) works very well. Seven foot (2.1 m) row spacing will leave a comfortable walkway. Six feet (1.8 m) between rows will usually leave just a little walking space. Five feet (1.5 m) between rows will form a dense, unbroken canopy.

Mashua is very tolerant about transplanting and you will get a head start by potting the tubers. You don’t have to pot them individually; you can put a bunch in a single container and then divide them when you transplant.

Mashua grows very quickly once it has sprouted. To keep potted plants manageable, you can trim the stems back to a few leaves. They will readily send up new stems from the remaining nodes, so you can be very aggressive in trimming them.

This plant likes to climb and will make more efficient use of space if it can. Interestingly, traditional Andean culture of mashua does not appear to have involved any trellising. Instead, the plants are just allowed to pile on top of the ground, forming a mound with about a two foot (60 cm) radius. Mashua can make a very good weed suppressing crop when grown in this fashion.

Planting Tubers

Plant whole tubers and seed pieces about two to three inches (5 to 7.5cm) deep (shallower for smaller pieces and deeper for larger). Orientation of the tuber doesn’t seem to matter. I usually plant them horizontally, but tubers are found in a jumble at harvest, so there is probably no right or wrong way to plant them.

You can cut tubers for more plants, much as you would seed potatoes. Make sure each piece has at least two eyes. It is best if the seed pieces are at least 1/2 ounce (14 g). If you cut tubers, let them heal for a few days in a humid environment before planting them.

Planting Seeds

Mashua seeds have slow and irregular germination. Start your seeds at least three months before you want to transplant. Plant seeds about an inch deep. The optimum germination temperature appears to be between 55 and 65 degrees F. Warmer temperatures inhibit germination. Soil should be kept damp. Under my conditions, the earliest seedling emergence has been 18 days, indicating that germination was probably about two weeks, since it takes the seedlings several days to emerge. There is a peak in germination at about 14 weeks, when about half the seed has germinated, followed by a very long tail out to two years or more. Scarification techniques, like chipping the seed with a nail clipper or filing improve germination time.

Mashua seeds undergo hypogeal germination – the cotyledons remain below the surface, so the first leaves that you see are true leaves. Once they break the surface, mashua seedlings grow very quickly and are typically ready to plant out in 2-3 weeks. As with many plants that germinate best in damp soil, you should dig out and re-pot mashua seedlings in drier soil soon after they emerge. Be careful digging out the seedlings, because the roots can be several inches long by the time the first shoot breaks the surface. I usually pinch out the tips of any stems by the time they reach six inches in length. This encourages a bushier seedling that will be less vulnerable to damage when planted out. Seedlings will otherwise often grow one very long stem and can be set back severely if some critter snips it off.

I have had mashua volunteers germinate in the field fairly early in the growing season here, including some from seeds that were buried as deep as four inches. This suggests that mashua can be direct seeded and adds more evidence that cool temperatures are probably most suitable for germination.

Management

Mashua is typically hilled up at least once during the growing season. At a minimum, this provides some protection to the tubers, which often grow up and out of the soil. It may also improve yields, although I have not observed significant differences in yield between plants that were hilled and those that weren’t.

Mashua will definitely benefit from hilling up or mulching if you are at risk of frost before harvest. It has a habit of piling up tubers right at the surface and these will be ruined in a frost if they are not protected. They will also turn green from exposure to the sun, which does not affect edibility, but can look less appealing.

Companion Planting

Companion Planting

Mashua is a difficult companion because its growth is so rampant. It can be used as an under-story plant in orchards with reasonably good results. In the Andes, mashua is sometimes grown as a border surrounding potato crops and is believed to deter pests (Grau 2003).

Growing as a Perennial

Like many tuber crops, mashua can be grown as a perennial, but it is difficult to manage. Where the soil doesn’t freeze deeply, all of the tubers will survive the winter and each will grow a new plant. Because mashua sets tubers very densely, there may be no room for the new plants to form a new crop. If you are growing mashua as an ornamental or as a leaf crop, you may not care about this, but when a tuber harvest is the goal, the only practical method for perennial growing is the “sloppy harvest” method, where you take the large tubers and leave the small ones to grow again. As always, this risks inadvertent selection for small tuber size.

Growing as an Ornamental

I am pretty much focused on growing plants as food and their appearance is a secondary consideration. However, since far more people grow mashua as an ornamental than as an edible, I would be remiss in skipping this subject entirely. The variety ‘Ken Aslet’ is widely available in the nursery trade as an ornamental variety. It flowers relatively early in the year, usually beginning sometime in August and continuing until the frost. It is a climber and can be and impressive plant on a trellis. Most other mashua varieties are short day flowerers and don’t begin until October/November, so they are only suitable for ornamental use in climates that are frost-free or nearly so. We have introduced a few varieties that have early flowering in August or September, including ‘Hahamish’ and ‘Suqualus,’ so it is possible to grow several varieties that flower in succession until the first frost kills the plants.

Almost all mashua varieties have the same flower color: a red/orange spur with yellow petals. There are a few exceptions though. The variety ‘Puca-añu’ has red petals, so the flowers have very little contrast and appear solid red. Unfortunately, this variety is a short day flowerer, so you will only get to see the flowers briefly, if at all, in most of North America. The variety ‘Hahamish’ has orange petals and generally flowers beginning in August, so it can be a good companion for ‘Ken Aslet’ if you want some contrast.

I have observed that nitrogen rich soil appears to delay flowering in mashua, so if you want early flowering, go easy on the nitrogen.

For more information, see our Flowering Schedule of Mashua Varieties.

Container Growing

Mashua grows very well in half barrel or larger containers. It is best not to trellis mashua when growing in a container, as the size of the

plant can easily exceed the resources available in the container.

Harvest

With the exception of the variety Ken Aslet and several of the evaluation varieties from our breeding program, mashua varieties have a short day dependency for tuber formation; they don’t begin to form tubers until day length decreases to 12.5 to 13 hours, which typically falls somewhere in the first half of September. About 10 weeks are required to form a good yield, which places harvest around the middle of November. Mashua will continue to grow much longer than that, so harvest can be delayed until the plants are killed by frost. Where harvest can be delayed until late December, yields can be very large. I have had single plant yields as high as 16 pounds (7.25 kg), nearly ten gallons of tubers, when mashua was given a very long growing season and grown on trellis.

Color develops late in mashua. This doesn’t matter for white varieties, but strongly colored varieties need to be left to mature as long as possible. If tubers are harvested before full color develops, they can be exposed to the sun for a few weeks. They will develop full coloration, but if the color isn’t intense enough to mask it, they will also turn green.

In the Andes, mashua is sometimes exposed to the sun for several days following harvest to sweeten the tubers (Grau 2003). I have tried this for as long as two weeks, but have not been able to detect any obvious change in the flavor of the tubers. It is possible that more intense sunlight is required.

In cold climates, there is some urgency to complete the harvest when temperatures of 30° F (-1 C) or below are imminent. Mashua sets many of its tubers at the surface of the soil and these will all be ruined if they are frozen. You can much over the base of the plants to avoid this problem.

Storage

Mashua is one of the more difficult of the Andean root crops to store. It dehydrates relatively quickly once dug. Tubers will last 6 to 8 weeks at room temperature and moderate humidity before the reduction in quality makes them unappealing for eating. Storage conditions of 35 to 38° F (2 to 3 C) and 95% humidity can extend storage to 8 months, allowing for some deterioration. Tubers exposed to light will become green, but this does not affect edibility.

Preservation

The only traditional method of preservation for mashua is a kind of low tech freeze drying similar to the process used to make chuño from potatoes. Mashua can also be preserved by pickling or canning, using processing instructions for potatoes. Some varieties discolor when processed for canning.

Propagation

Mashua is a polyploid crop and all varieties are hybrids, which can only be maintained by replanting tubers. Unlike many of the Andean root crops, mashua easily sets germinable seed, which can be used to breed new varieties.

Vegetative Propagation

Mashua is easily propagated from tubers. It can also be propagated by cuttings.Take six to nine inch sections of stem and set the bottom about two inches deep in damp soil. Significant root formation takes four to six weeks, after which the new plant can be hardened off and moved outside. Do not pull the full stem free of the tuber. Unlike most of the other Andean tubers, mashua responds very poorly to this technique and the tuber will often rot once you have pulled the dominant sprout.

I recommend saving the largest tubers for replanting. Larger tubers generally produce bigger plants faster, with more stems, which leads to greater yield. Tuber crops are also prone to somatic mutations, so you can inadvertently select for varieties that produce smaller tubers by repeatedly planting the smallest.

Sexual Propagation

Mashua, like most plants that are propagated vegetatively, is naturally a hybrid. It sets seed easily in a favorable climate, although not until very late in the season, so frost/freeze protection may be required to mature seed. The seed, since it is produced by heterozygous plants, will not be true to type. Instead, it will produce new varieties of mashua, some of which may prove to be superior (but most of which won’t). That said, the self-pollinated progeny of most mashua varieties have a great deal of consistency in phenotype. I suspect that most heirloom varieties are the result of repeated self-pollination events, such that they are substantially homozygous. In comparison, after making a cross between two varieties, the self pollinated progeny of that new variety display substantial variation. This is very similar to the behavior of tetraploid potatoes.

Each flower can produce up to five seeds, but it is rare to see more than two without making hand pollinated crosses. In my experience, flowers that are brush pollinated by the same variety produce a little more than one seed per flower on average. Flowers that are cross pollinated produce closer to three seeds per flower. Some varieties set large numbers of seeds with open pollination while others set very little seed even when they flower abundantly. There might be some self-incompatibility in mashua or it could be that some varieties just have poor pollen fertility. I haven’t made crosses in a comprehensive enough fashion to guess which case is more likely.

Hummingbirds are the only really enthusiastic pollinators of mashua here, but I also often see bumblebees working the flowers.

When fully dried, there are approximately 30 mashua seeds per gram in seed collected from mixed varieties. Varieties differ in seed weight by about +/- 30%. Fully mature seed has much better germination than immature seed. The size of mashua seeds is correlated with germinability: bigger is better.

Problems

Pests

Although mashua usually grows fast enough to outpace them, there are a few pests that like to nibble on it. The most serious serious pest of mashua is deer. A couple of deer can destroy a large planting of mashua overnight. Among insect pests, the worst are probably the larvae of cabbage white butterflies, which can cause a lot of damage when they are present in large numbers. Flea beetles and aphids can also cause problems, although they tend to be more severe in greenhouses. The other common problem pest is field mice (voles), which will dig and eat the shallow tubers. They typically ignore them until late in the season, when mashua is one of the few plants left in the ground and they are never enthusiastic about digging them up. An unusual, but more serious problem is bears! Bears will dig up your mashua and eat every bit of it that they can find. Our geese also learned to eat mashua and will actually push their heads into the soil to get at the tubers.

Diseases

Mashua is one of the least studied of the Andean root and tuber crops. Little has been written about its diseases but that is not an indication that it doesn’t have any. Mashua is probably vulnerable to at least some of the pathogens that infect the garden nasturtium (T. majus), which makes it likely that it could contract novel diseases outside its native region.

Bacteria and Fungi

The cercozoan Spongospora subterranea, which is responsible for the condition known as powdery scab in potatoes also affects mashua (Torres 1992). It does not reduce edibility significantly, but it does affect the appearance of the tubers. I have found no pictures or accounts of the symptoms, but powdery scab is present in the USA, so I expect we’ll see it eventually.

Mashua tubers grown in wet conditions, particularly in warmer soils, sometimes suffer from a brown staining, which appears to be bacteria. Although it is generally only a cosmetic condition, it can be severe in some cases, and can reduce the storage life of the tubers.

Viruses

Mashua is potentially infected by a large number of viruses, in contrast to its reputation as a very disease resistant plant. I have found only a few viruses infecting mashua in the USA, which is good reason to avoid introducing new, untested varieties. Recognized viruses of mashua in the Andes include Papaya Mosaic Virus, Potato Virus T, Sowbane Mosaic Virus, and Tropaeolum Mosaic Virus (FAO 2007). Many more viruses have been found infecting mashua where it comes into contact with other crops.

Mashua varieties in North America frequently test positive for a Potyvirus, which could be Bean Yellow Mosaic Virus, Mashua Virus Y, Tropaeolum Mosaic Virus, Turnip Mosaic Virus, or as yet unidentified mashua viruses. Plants that test positive for this virus usually show a fine, light mosaic on older leaves, but a few varieties develop much more severe symptoms, like those shown in the picture. This virus was present in the varieties Blanca, Ken Aslet, and Sapu-anu, but was mostly asymptomatic except when plants were under stress. Any variety that was grown in the same area as these in the past should be assumed to be infected, whether it shows symptoms or not.

Other viruses that I have seen at least once are Cucumber Mosaic Virus, which showed strong mosaic symptoms, and that equal opportunity pathogen of Andean roots and tubers, Papaya Mosaic Virus, which was asymptomatic. Despite routine testing and growing only from a virus free foundation crop, I occasionally find a plant that is Potyvirus positive, which leads me to suspect that this virus may have other wild or weedy hosts. I have occasionally gotten positive test results for Potato Virus Y in mashua, but antisera for PVY are known to be cross-reactive with those of some other Potyviruses and such a cross reaction has been reported for Tropaeolum Mosaic Virus (TropMV), so I suspect another mashua Potyvirus is the real culprit, since it would be very surprising if PVY infection were possible but never yet reported.

There are a few viruses that might be able to transmit through seed in mashua, but they are not yet known to be present in North America. So far, I have not seen any virus infections in seedling mashuas.

| Virus | Genus | Present in USA | Frequency in Mashua (USA) | Seed Transmitted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bean Yellow Mosaic Virus (BYMV) | Potyvirus | Yes | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in mashua |

| Beet Curly Top Virus (BCTV) | Curtovirus | Yes | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in mashua |

| Broad Bean Wilt Virus (BBWV1 and BBWV2) | Fabavirus | Yes | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in mashua |

| Cherry Leaf Roll Virus (CLRV) | Nepovirus | Yes | Unknown/Not Detected | Possibly in mashua |

| Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV) | Cucumovirus | Yes | Infrequent | Possibly in mashua |

| Mashua Virus Y (MasVY) | Potyvirus | Possibly* | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in mashua |

| Papaya Mosaic Virus (PapMV) | Potexvirus | Yes | Infrequent | Unlikely in mashua |

| Pea Early Browning Virus (PEBV) | Tobravirus | No | Unknown/Not Detected | Possibly in mashua |

| Potato Virus S (PVS)** | Carlavirus | Yes | Rare | Unlikely in mashua |

| Potato Virus T (PVT) | Tepovirus | No | Unknown/Not Detected | Possibly in mashua |

| Sowbane Mosaic Virus (SoMV) | Sobemovirus | Yes | Rare | Possibly in mashua |

| Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) | Tobravirus | Yes | Unknown/Not Detected | Possibly in mashua |

| Tomato Aspermy Virus (TAV) | Cucumovirus | Yes | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in mashua |

| Tomato Black Ring Virus (TBRV) | Nepovirus | No | Unknown/Not Detected | Possibly in mashua |

| Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus (TSWV) | Tospovirus | Yes | Infrequent | Unlikely in mashua |

| Tropaeolum Mosaic Virus (TropMV) | Potyvirus | Possibly* | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in mashua |

| Turnip Mosaic Virus (TuMV) | Potyvirus | Yes | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in mashua |

| Verbena Latent Virus (VeLV) | Carlavirus | Yes | Unknown/Not Detected | Unlikely in mashua |

* Mashua varieties have tested positive for the genus and these viruses are possible culprits

** I have seen positive results for these viruses in heirloom mashua varieties. It is possible, even likely, that these are cross reactions for closely related viruses, since PVS and PVY have not been reported to infect mashua.

Defects

Mashua frequently demonstrates fasciation, which can be beautiful, but also typically lowers yield. the cause is unknown, but fasciation is sometimes an indication of virus infection. Another common defect is flowers with dual nectary spurs. this may be genetic and appears to cause no problems with seed formation.Breeding

Crop Development

Breeding objectives for North America are similar to those for oca and ulluco. As a plant that is both dependent on short days for tuber formation and vulnerable to frost, mashua cultivation is limited to climates with mild autumn weather. Varieties that form tubers in longer days will allow expansion into other regions with cool summers but early frosts. Several varieties with critical daylengths greater than 13 hours now exist and breeding this trait into new varieties appears to be relatively easily, with roughly 3% of the progeny of crosses between short day and intermediate daylength varieties having similar intermediate photoperiods. Breeding for greater tolerance to heat and drought would further expand the possible range for mashua in North America. New varieties should be trialled in warmer climates.

No discussion of mashua breeding objectives would be complete without considerations of flavor. Mashua has two flavor components that people seem to find objectionable: the aniseed flavor and the pungent, mustard flavor. Either one of these might be more acceptable given the absence of the other. Breeding to reduce the pungency, likely associated with isothiocyanate content, might also reduce the content of substances implicated as anaphrodesiacs, which could increase consumer acceptance whether or not these substances actually exist in biologically significant concentrations.

Genetics

As with most of the Andean root and tuber crops, little is known about the genetics of mashua. The trait of greatest interest in my breeding work is day neutral flowering, which is known only from the cultivar ‘Ken Aslet’. I have grown many self-pollinated seedlings of this variety and also have made crosses with short day flowering varieties. The behavior of the progeny has yet to make the mode of inheritance clear. It is important to note that flowering may not appear until the plants are grown from tubers. I initially screened plants in their seedling year and unfortunately culled many plants, some of which, I later learned, would probably have been early flowerers in their second year.

Relatives

Mashua has a number of edible wild relatives. Most people are aware that the leaves and seed pods of the common garden nasturtiums, T. minus and T. majus, are edible. There are also several edible tuberous species. In addition to those listed, T. brachyceras is said to have edible tubers, but I haven’t tried them.I have had no luck making crosses between mashua and common Tropaeolum species (which doesn’t mean that it can’t be done), but there is a cluster of close genetic relatives that might be worth trying, including T. cochabambae, T. smithii, T. argentinum, T. meyeri, T. wamingianum, and T. capillare. Unfortunately, these species are difficult to obtain. If you know of a source for any of them, please hook me up!

Tropaeolum leptophyllum

This species has good tuber size but flavor is a challenge. If you feel that the flavor of mashua is just not intense enough, this might be the plant that you have been looking for. Please see a doctor about your taste buds.

Tropaeolum sessilifolium

The tubers of this Chilean species are small but lack the odd floral taste of mashua tubers, so they might make an even better edible with some work. Yields are small, sometimes only one tuber. That would need to be improved for this plant to be much of an edible.

Tropaeolum tricolorum

The tubers of this species taste rather similar to mashua, but are smaller and more fibrous. They aren’t hopelessly small though, so this plant might have some potential as an edible.

Learn More

There aren’t many good sources of information about mashua on the web. Here are some of the best that I have found:

- Download a free PDF of Lost Crops of the Incas. It is a great introduction to Andean crops, although somewhat out of date.

- Check out Crap Crops of the Incas on Radix, a classic!

- Mashua: Tropaeolum tuberosum PDF from Bioversity International

15 thoughts on “Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum)”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

According to this study, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7057655 , “Experimental animals and controls showed equal capability in impregnating females, although animals fed T. tuberosum showed a 45% drop in their blood levels of testosterone/dihydrotestosterone.” This is the opposite of what you stated above.

Thanks for your comment C.G. I did read this study in my research, but ended up leaving it out because it used uncooked tubers and I didn’t feel like that represented how most people will use mashua. More information is usually better though, so I have updated the page to include a summary of the Johns study as well.

All these informations are really interesting.

I’ve grown tropaeolum argentinum for some years. This is a difficult species to germinate but when the plant starts it flowers freely and sets a lot of seeds.

I have some stock.

I would love to try and grow this.. what are the chances of obtaining either seed or tuber from you? Please thank you of coursed I would purchase

You have some amazing information here. I blog about unusual food plants, and ALMOST decided to skip mashua since you have done such a bang-up job. Where is your nursery located?

This is a really informative and comprehensive article about this plant apart from one thing – where the F can I get the seeds or tubers I can’t find them anywhere (UK).

I can’t find them anywhere (UK).

The UK and EU plant health authorities went on quite a rampage about the Andean tubers a few years back due to the presence of quarantine viruses in many of them. I get the impression it has become a lot more difficult to get them since then. eBay is probably the place to look, although you are taking some risk.

Would you say that the leaves and flowers taste similar to garden nasturtiums?

Yes, they are pretty similar. Mashua might be a bit more peppery.

I ordered two Suqualus Mashua tubers and planted them on March 29, 2022. How long does it take them to sprout? I’m in the Pacific Northwest, WA state, and the weather has been cooler than usual for early March, but no freezing.

Hi Joan. Suqualus has long dormancy. Mine haven’t sprouted yet either. They will probably pop up soon.

Hello Bill, Really enjoyed the in depth info on Mashua here. I found your site while checking to see if any one else is producing Seeds that come true to type and as far as I can find, your site is the only page that even mentions seeds. We only have Bumble Bees here that pollinate them. The honey bees will not touch them unless there is a huge amount of them. Any thing less then a 30ft hedge full of themn and they are just not interested. The mashua we grow has distinct sets of 3 seeds and this variety is said to have been isolated for over 2 decades. The only time it does not come true from seed is if another variety is close by and gets crossed by bees. The variety we have is Buddaree Its quite pleasant cooked or raw. I cannot find any reference to this type any where online. Originally from a farmers market 1990s Agree 110% about the Temperature range. We find soaking the stored seeds in warm water and letting it cool and stand for 24 hours prior to planting. Damp paper towel in a zip lock back 2-3 days in the fridge seems to wake the seeds up when taken out and left at 15c/59f As for cultivation Its best to eat all the smaller ones and leave the big ones. They just get bigger each year and more productive. So it seems in my experience.

Fascinating, Colin! I’ve never heard of that variety and it is wonderful that there are still more out there to discover. It is probably not really true from seed in the sense that is usually meant. Most likely, it has uniform appearance, but the seedlings could be distinguished from one another genetically. That is a difference that would likely only be important to a specialist though. My expectation, having carefully isolated and self pollinated single varieties, is that their productivity quickly declines. By having multiple plants grown from seed with slightly different genetics, you probably avoid the problem of inbreeding depression. My guess would be that it is a white variety with long tubers. The most likely heritage in that case would be the variety Sidney, which is probably part of a group of self pollinated varieties that includes the very common variety Blanco and a number of other names. Sidney has been grown in the UK for about a century, although it appears that it mostly lost its name along the way and is commonly just traded under the species name now. The only other common UK variety until fairly recently was Ken Aslet, a yellow variety with darker stripes and spots. If Buddaree is anything other than a white variety, that would be very surprising and interesting. It sounds like you have quite a mashua friendly climate and an excellent place to do some breeding, something that very few people anywhere in the world are working on.

I would love to try Mashua in my Central Texas garden. I think it might grow in Winter. I can start it in pots in my sunroom and transplant out in January or Feb for cool growing season. I’ve heard the heat can kill it, but that happens to my tomatoes too, but I still manage to get good harvests. just not in the summer.

It is pretty vulnerable to heat, but determined people manage to grow these plants in a lot of surprising places.