Edible Dahlia (Dahlia spp.)

Edible Dahlia (Dahlia spp.)

About Edible Dahlias

Description

Odds are that you are already familiar with dahlias and perhaps already grow them as ornamentals. Most people grow dahlias for their flowers without ever realizing that they are a possible food source as well. The only difference between edible dahlias and common garden dahlias is perception, but I use the term edible dahlias a lot, simply to aid people in finding the right information. There are many thousands of web pages about dahlias, but only a few about edible dahlias. Dahlia tubers were eaten by the indigenous peoples of Mexico since long before the arrival of Europeans. The dahlia family is complex, with many species. It is possible that all dahlia species are edible, but I am focusing on just two for which there is a clear record of human use: the common garden dahlia (D. x pinnata or D. variabilis) and D. coccinea. We don’t know conclusively what species contributed to the common garden dahlia, but the most recent hypothesis that I have read suggests that it is D. coccinea x D. sorensenii. Of course, breeders have continued to cross the garden dahlia with other dahlia species, so it may not be possible to untangle all of the contributions at this point. This is a very similar situation to the potato, which has now been crossed to so many of its wild relatives that many pedigrees can be traced back to more than one wild ancestor. There is a lot of room in the Dahlia genus for further exploration and experimentation. See the Other Species section below for more information.

Dahlia tubers come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and colors. The types that are best for eating are usually comparable in size to boiling potatoes. Some are short and rounded. Others are relatively long and thin. Many are white in color, but they range from white to tan to red to blue-gray. Yields can reach at least four pounds (1.8 kg) for a plant given a long growing season and plenty of water, but are more typically about two pounds (1 kg). I am following convention here in referring to dahlia storage roots as tubers, even though they are not technically tubers, because they do not have buds. They are also definitely not bulbs. Technically, they are storage roots, just like yacon. But, rather than tilt at that windmill, I will call them tubers henceforth.

The size of common dahlia plants ranges from small, two to three foot (60 to 90 cm) tall plants that can be grown in containers to five foot (1.5 m) tall monsters. In my experience, there is not a strong correlation between the size of the plant and tuber yield, although this probably is a result of breeding for characteristics other than tuber yield. I find the smaller dahlias to be more convenient for cultivation and tend to prefer plants that reach about three feet and maintain an orderly form. The variety Yellow Gem is very nice in this regard.

There is abundant information available about growing dahlias as ornamentals, so I am focusing on information of particular relevance to growing dahlias as edibles in this chapter. You can find tons of additional information about growing dahlias on the Internet or at your local library.

The tubers of edible dahlias are somewhat similar to yacon or jicama raw. The texture is crisp and juicy. The dominant flavor ranges from bland and starchy to mildly sweet, sometimes with an aftertaste that is either flowery or similar to radish. This is the range of flavors that I have experienced in the varieties that we have selected for use as edibles, but there is a greater range of flavors in ornamental dahlias, many of them unpleasant.

Are you interested in searching out new edible dahlias from among the thousands of ornamental varieties? Grow them out and give them a try. I’ve seen a number of rules of thumb for finding tasty dahlias: choose red varieties, choose yellow varieties, choose red or yellow varieties, choose only cactus varieties, choose only old varieties, etc. I have tasted almost three hundred different dahlia varieties and have not found any of those rules to be very useful so far, with the possible exception of older varieties. While not every old heirloom tastes good, a slightly higher percentage of those that I have tasted have had good edible qualities. If you are already growing dahlias, why not give them a taste test? If you find one that you really like, please let me know.

The common dahlia is an allopolyploid of octoploid configuration. It is genetically complex, with a great deal of built in diversity, as attested to by the wide range of ornamental varieties.

History

Dahlias are native to high elevations in Central America, where they have probably been used as a wild and semi-domesticated food plant for thousands of years. Different species have been used for different purposes: some for food, some for medicine, and some even as a source of water.

Edible dahlia tubers are still a somewhat common food in parts of Mexico, but it is debatable how much of a role they have played in the human diet in the past. They have probably been used irregularly as an emergency food following the introduction of corn (Whitley 1985). The Pima people of Arizona and Sonora included D. coccinea in their traditional diet, at least as a famine food.

The dahlia was introduced to Europe in 1788. By 1841, a dealer in England carried more than 1,200 varieties (Harshberger 1897). Experiments with dahlias as an edible crop in Europe in the 1800s were less successful, with the tubers variously described as both unpleasant tasting and tasteless (Whitley 1985).

Dahlia is probably best known as a food product for Dacopa, a product made from roasted dahlia tubers that was used as a coffee substitute. It was invented by William Mitchell, the creator of Cool Whip, Jell-O, and Tang, among other tasty horrors (Steyn 2004). It seems that the coffee market went in a more upscale direction and Dacopa disappeared, although it is always possible that it will be resurrected by clever marketing. Perhaps someday people will be lining up at Starbucks for no-caf Dacopa lattes.

Nutrition

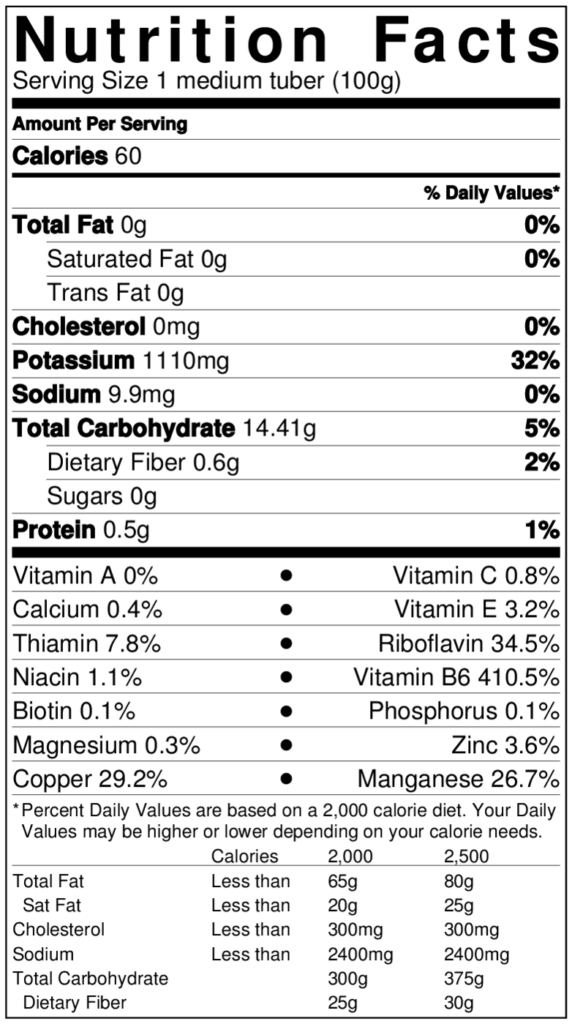

Dahlia tubers are primarily a source of the indigestible carbohydrate inulin (Whitley 1985). Inulin is the primary storage carbohydrate of Jerusalem artichoke and chicory, other members of the sunflower family. Inulin is poorly tolerated by some people and can cause significant gas and sometimes cramping, so it is best to start slowly when eating dahlias for the first time. Most people have no problems, but you’ll be happier not to have bolted down a large serving if it turns out that you are sensitive to it. I can only consume small portions of inulin rich foods and I can attest that the consequences of over consumption are not pleasant.

Edible dahlia is a good source of potassium, riboflavin, and vitamin B6. Mineral content may vary significantly depending on the soil that the plants are grown in, but it also appears to be a good source of copper and manganese. Different varieties were found to have significant differences in composition (Nsabimana 2011).

Cooking and Eating

Dahlia tubers can be eaten raw or cooked. It is best to peel them, as the flavor of the skin is often unpleasant.

The flavor of dahlia tubers changes with storage. When first harvested, they are crisp and fairly bland, with a taste something like celery. There are also often spicy or bitter flavors at this stage. With storage, some of the inulin converts to fructose and the tubers become sweeter.

Other Species

We know that edible dahlias were used as food in the past in Mexico. We know for certain that D. coccinea and D. pinnata were used as food. Unfortunately, since dahlia taxonomy is a modern invention, we don’t really know if other species were used as food or not. I suspect that most Dahlia species have edible tubers and that they were probably eaten in the past, but the evidence for this is poor. Normally, I avoid testing foods for which there is not a clear record of human use, but because this appears to be a relatively safe plant family and because hybridization between different species is so common, I have tested several other species as edibles. Be cautious if you decide to try these species. We need more experience with these species to be sure that they are safe to eat regularly or in large amounts.

The Dahlia genus is divided into four sections. The divisions are morphological rather than genetic, so there may be surprises coming for dahlia taxonomy in the future, much as there have been for potato. Nevertheless, these divisions may be useful for edible dahlia prospecting. The dahlias with a history of edible use fall into the sections Dahlia, which includes D. coccinea and D. sorensenii and many lesser known species, and Pseudodendron, the tree dahlias, which includes D. campanulata, D. excelsa, D. imperialis, and D. tenuicaulis. As far as I know, the other two sections, Entemophyllon and Epiphytum, contain no species with a history of use as edibles.

Section Dahlia

Dahlia australis

I have tasted only a few bites of this species, but it did not taste significantly different than D. pinnata and I had no ill effects.

Dahlia merckii

Flavor very similar to D. coccinea. No ill effects.

Dahlia sorensenii

Tubers were sweet and juicy. Only a small amount consumed to date. No ill effects.

Section Pseudodendron

Dahlia campanulata

Tubers are very large and do not appear to be fibrous. I haven’t tasted this species yet.

Dahlia imperialis

Tubers were a bit fibrous and the skin had a strong resiny flavor. No ill effects, but I didn’t find this species very appealing. The leaves are traditionally eaten by the Kekchi people of Guatemala (Booth 1992). They are boiled and then either consumed directly or fried in lard.

Dahlia tenuicaulis

Tubers from a mature plant were thin, barely qualifying as tubers, and were too fibrous to eat.

Cultivation

Climate Tolerance

Dahlias are native to volcanic highlands in central America and extend from the southern border of the United States to Costa Rica. Their region of greatest diversity is south of Mexico City. Most grow at altitudes higher than 7000 feet (2133 m), making them adapted for mild, humid, frost free climates.

Although dahlias grow well in mild, temperate climates, their native climate is wet in the summer and dry in the winter, the opposite of what will usually be found in North America. As a result, we must take efforts to ensure that dahlias are well watered during the summer and protected from excessive moisture during the winter.

There are a few considerations that you should observe when growing dahlias for edible tubers. Dahlias need plenty of water, but this is even more critical when growing them for food. When grown without sufficient water, tubers tend to be resinous and unpleasant tasting. You should also go easy on the fertilizer. Too much nitrogen will produce abundant top growth, but poor tuber yields.

Photoperiod

Dahlias require long days for flowering, with more than 12 hours of daylight. For tuber formation, they require short days, with less than 11 to 13 hours of daylight, depending on variety. This means that your tuber yields will be better if you can keep the plants alive as long as possible in the fall. You may want to employ some kind of frost protection in short season climates.

Soil Requirements

Dahlias like well drained, sandy soils, with a mildly acidic pH, similar to the volcanic soils that are found in their natural environment.

Dahlias do not produce high quality tubers in wet soil. Frequent shallow watering and plenty of organic matter in the soil is a good strategy to keep the plants fully hydrated without becoming waterlogged. Drip systems work very well for dahlias.

Propagule Care

Dahlia tubers are particularly vulnerable to dehydration and will do better stored in soil than exposed to the air. Keep them in a dark, cool place, in slightly damp soil. Tubers will quickly wither and become fibrous when exposed to air, but they can be rehydrated simply by potting them in some damp soil.

Planting

Tubers

Dahlia tubers are generally planted in spring, once the risk of frost has passed. Where spring weather is very wet, it is sometimes better to wait until the weather dries out or to pot the dahlias and transplant once they are growing well. For the best tuber production, dahlias should be located in full sun in an area with well drained soil.

Cut tubers free of the clump, including a piece of the stem to which they are attached. The buds are located very near to the stem and tubers cut farther back will generally not sprout. Plant two to three inches (5 to 7.5 cm) deep, preferring deeper planting for larger tubers. Orientation of the tuber doesn’t appear to matter.

In row spacing of two to three feet (60 to 90 cm) works well. Use the wider spacing for taller varieties. Tighter spacing should only be used where water is abundant. Don’t crowd dahlias when you are growing for tuber yield. Four foot (1.2 m) row spacing will usually leave a walkway, but some varieties may sprawl if not staked.

Seeds

Dahlia seeds should be started about eight weeks before you intend to plant them out. Plant seeds about 1/4 inch deep. Optimum temperature for germination is about 70 degrees F (20 C). Some species germinate better at lower temperatures; for example, I have observed that D. coccinea and D. merckii germinate fastest at about 60 F. A transplant at four weeks, burying the seedling up to its top set of leaves, results in sturdier seedlings, but it isn’t required. Seeds of D. australis and hybrids between D. australis and garden dahlias are slow to germinate – as much as two weeks later.

You can produce mini-tubers after 8 weeks by limiting water and reducing light to 12 hours per day. This is also a good way to screen seedlings, since those that produce the largest mini-tubers appear to also form larger tubers at maturity.

Management

When growing dahlias for their flowers, it is necessary to remove spent flowers in order to keep the plant from forming seeds, which takes energy from further flower production. When growing for tuber yield, you don’t need to remove flowers until after the autumn equinox, when tuber production begins in earnest.

Little information is available on increasing dahlia tuber yields, but I have experimented with preventing flowering and achieved nearly a twenty percent increase in yield when all flower buds were pinched off. Most people will probably choose not to pinch the flowers. I usually prefer to let them bloom, despite the lower yield.

Companion Planting

Dahlia is often planted with other flowers, which is a fairly sensible arrangement. Most annual flowers will not compete with dahlia for root space.

Growing as a Perennial

In mild climates with dry winters, dahlia can be easily grown as a perennial. It will sprout from the crown in spring and tuber yield will increase in subsequent years. I’m not sure about the palatability of dahlia tubers that have been grown for more than one year, since we can’t grow them as perennials here, but I suspect that they may lose some quality. The tubers that have been used to propagate the plant are often fibrous, but the amount of energy that the new plants draw from those tubers is likely to be greater than what is taken from an intact crown.

Container Growing

Dahlia grows reasonably well in large containers, but you have to manage water carefully.

Harvest

In most of North America, dahlia plants will eventually be killed by frost. Harvest any time after the top growth dies. In exceptionally mild climates, the tubers can continue to grow right through the winter and can be harvested in spring.

With dahlia, you propagate the plant at the same time that you take your harvest. This is detailed in the propagation section. There will be some tubers that you can’t cut cleanly or that don’t have an obvious bud; you should cut those free and reserve for eating. If you don’t want to increase the number of plants that you grow, you only need to keep one tuber for propagation and you can eat the rest.

Storage

Although the tubers keep reasonably well out of the ground, they don’t remain in good condition for eating for very long. They dehydrate rapidly unless they are stored under cool, high humidity conditions. Because of this, they are best stored in soil. They also keep reasonably well under storage conditions of 38° F (3 C) and 95% humidity.

Preservation

I am not aware of any traditional or modern preservation techniques for dahlia tubers. It is probably possible to slice and dry tubers, as is done with yacon.

Propagation

Dahlias are generally propagated with tubers. All varieties are hybrids which can be maintained only by clonal propagation.

Vegetative Propagation

Dahlia is easy to propagate from tubers, seeds, and cuttings. The buds on a dahlia tuber are found near the intersection of the stem with the tuber. You must carefully cut free your propagation tubers so that they include a bud. The buds are difficult to see without practice, but if you cut right at the intersection with the stem, you should end up with a viable tuber. I recommend that you store the propagation tubers in soil, which usually keeps them in good condition and helps to preserve dormancy.

You can also propagate dahlia with cuttings. The easiest cuttings to root are those that are cut free of the tuber, but any stem cutting can be rooted in damp soil; cuttings from higher on the stem simply take more time to form roots. Take a six to eight inch (15 to 20 cm) section of stem, strip off all but the top set of leaves, and set the bottom three inches (7.5 cm) in damp soil. The cuttings are usually ready for hardening off and transplant within six weeks.

Sexual Propagation

Dahlia is a genetically complex genus, but most of the garden dahlias are allopolyploids of octoploid configuration (Bate-Smith 1955). Inheritance of some features is duplex, meaning that it is similar to that of diploids, while other traits are quadriplex and therefore have much less predictable inheritance. Heritability of flower color and form have been studied, but there is little information available about inheritance of tuber traits. Oh well, something new to learn!

If you want seed, don’t deadhead your dahlias. Let those seed pods mature. It takes at least four weeks from when the flower is spent until the pods have mature seeds. Once enough time has passed, I cut the whole flower stem, bring the pods indoors, cut the tip off the pod, and hang them upside down to dry. A dahlia pod can contain a lot of water in a wet climate and if you don’t open the pod so that the water can escape, your seeds may rot.

If you want seed, don’t deadhead your dahlias. Let those seed pods mature. It takes at least four weeks from when the flower is spent until the pods have mature seeds. Once enough time has passed, I cut the whole flower stem, bring the pods indoors, cut the tip off the pod, and hang them upside down to dry. A dahlia pod can contain a lot of water in a wet climate and if you don’t open the pod so that the water can escape, your seeds may rot.

If you grow both ornamental and edible varieties, you might want to hand pollinate so that your seed carries primarily the traits of the edibles. Or, you might want to let them cross for a wider range of traits. The first strategy is likely to be more efficient, but the second may produce new and interesting results. Hand pollination is easy to do with a small paintbrush. In some complex dahlias, you may need to remove petals for easier access to the stamens.

I see lots of pollinator interest in dahlias, including honey bees, bumble bees, hover flies, and other small native bees and flies. It doesn’t seem like there should be any problem with seed production in the Pacific Northwest.

Problems

As with the rest of this chapter, I am focusing on pests and diseases that are relevant to tuber production. Dahlias have many cosmetic problems which are covered in good detail in books about growing them as ornamentals. Cosmetic problems with the flowers and foliage don’t always affect the tubers.

Pests

Slugs are about the only significant dahlia pest that we see. They can do a great deal of damage to sprouting plants in the spring and will enthusiastically tunnel into tubers wherever they become exposed.

Diseases

Bacteria and Fungi

Black rot of the lower stem is common in wet climates. Control by making sure that your soil drains well and by planting in mounded soil. The cause is probably our old nemesis Erwinia carotovora which infects many of the plants in this guide. Destruction of infected plants is recommended in order to limit spreading.

Another common pathogen, Verticillium, causes wilts in dahlias, particularly at warmer temperatures. It is hard to avoid this ubiquitous soil organism. Keep soil moist but not wet and rotate between dahlias and plants that are not hosts for Verticillium to control its spread.

Viruses

Dahlias are vulnerable to a number of viruses, principally Tobacco Streak Virus, Dahlia Mosaic Virus, Dahlia Common Mosaic Virus, Cucumber Mosaic Virus, Potato Virus Y, Impatiens Necrotic Spot, and Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus. The disease is carried over in the tubers, so it is a good idea to destroy (by eating) infected plants.

Tobacco Streak Virus is common in dahlias in the Pacific Northwest and probably the rest of the country as well. If you have more than a few varieties, you’re very likely to have the virus. This one is often asymptomatic or has only very subtle symptoms. I am starting to get better at recognizing it now that I have been testing. The leaves of infected varieties tend to be a little less glossy than those of healthy plants. One of its more obvious symptoms can be a change in flower color. Varieties that normally have dark purple flowers can develop lighter red or pink flowers due to gene silencing by the virus (Deguchi 2015). TSV is transmitted through true seed of dahlia, at least occasionally.

Dahlia Mosaic Virus is a special case, as it is transmitted reliably through true seed and seed tested from three commercial sources in the US was infected with the virus (Pahalawatta 2007). In another study (Pappu 2005), 85% of samples from nine states tested positive. This virus is often, perhaps even typically, asymptomatic, so it is very common among dahlia collections. The virus is found world-wide and seed test results suggest that it may be nearly ubiquitous in this country. And there is a further complication: it may be reconstructed from pararetroviral sequences embedded in the dahlia genome that we cannot remove. If that is true, plants that test completely clean could later become infected from their own genomes. So, the question is: how concerned should we be? As a breeder, my feeling is that we should breed for varieties that are asymptomatic and not otherwise worry about it. As a seed supplier, I would like to ensure that I don’t spread the disease, but I’m not sure that is a realistic goal. As a compromise, I don’t sell tubers of varieties that I believe to be infected, but I can’t really confirm one way or another. Fighting this one may be an exercise in futility.

Potato Virus Y is a another virus that you should take note of. It is often asymptomatic in dahlia, but can be a serious virus in potatoes. For years, I couldn’t figure out where I was getting reinfection with PVY and then I read that the virus could infect dahlia. Testing revealed that two of our varieties were harboring it. You might want to keep some distance between dahlias and potatoes, as the virus is spread by aphids. Dahlias may also harbor Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid (PSTVd) asymptomatically. PSTVd infected dahlias are known to be present in Japan. It has been reported that PSTVd does not spread through pollen or seed in dahlia, but the research was so limited that I would not want to count on it.

Dahlias may also be infected with an endogenous pararetroviral sequence (EPRS) known as DvEPRS that originated in a caulimovirus, probably Dahlia Mosaic Virus. Essentially, part of the DMV genome became incorporated into the dahlia genome. In one study, it was detected in over 90% of samples and confirmed to be seed transmitted (Eid 2014). Under some conditions (possibly stress), when a complete EPRS exists in the host genome, the complete viral genome can be exported, causing infection with the original virus (Chabannes 2013). This might explain why Dahlia Mosaic Virus is so widespread. It is not currently possible to eliminate an EPRS from the host genome. It also isn’t completely clear to me that you would want to. Dahlia is known for its amazing variability of traits. It seems possible to me that the random incorporation of pararetroviral sequences into the genome might be responsible for some of that. It will be interesting to see how the research develops on that front.

| Virus | Genus | Endemic in North America | Frequency in Dahlia (USA) | Seed Transmitted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chrysanthemum Stunt Viroid (CSVd) | Pospiviroid | Yes | Rare | Possibly |

| Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV) | Cucumovirus | Yes | Uncommon | Probably |

| Dahlia Common Mosaic Virus (DCMV) | Caulimovirus | Yes | Common | Unknown |

| Dahlia Latent Viroid (DLVd) | Hostuviroid | Yes | Uncommon | Unknown |

| Dahlia Mosaic Virus (DMV) | Caulimovirus | Yes | Common | Yes |

| Impatiens Necrotic Spot Virus (INSV) | Tospovirus | Yes | Uncommon | No (Rarely) |

| Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid (PSTVd) | Pospiviroid | Yes | Rare | Possibly |

| Potato Virus Y (PVY) | Potyvirus | Yes | Uncommon | No |

| Tobacco Bushy Top Virus (TBTV) | Umbravirus | No | Unknown/Not Detected | Unknown |

| Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) | Tobamovirus | Yes | Uncommon | Unknown |

| Tobacco Streak Virus (TSV) | Ilarvirus | Yes | Common | Possibly |

| Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus (TSWV) | Tospovirus | Yes | Uncommon | No (Rarely) |

Defects

Dahlias should be harvested promptly once the top growth dies. In wet climates, water can infiltrate the crown through the hollow stem and cause rotting. The tubers are still edible, but you may not be able to salvage any propagation material.

Crop Development

Although the history of human use of dahlias as food is rather sketchy, it appears that they were mostly a wild or semi-domesticated food plant. Varieties were not heavily selected for use as food, or if they were, the history of this has been lost. So, in many ways, we’re starting from scratch.

Although the history of human use of dahlias as food is rather sketchy, it appears that they were mostly a wild or semi-domesticated food plant. Varieties were not heavily selected for use as food, or if they were, the history of this has been lost. So, in many ways, we’re starting from scratch.

One early decision that any breeder should make is whether they are growing dahlias as a pure food crop, where flowering is a secondary concern, or as an ornamental edible, in which both flowers and tubers are important products.

For a pure food crop, day length neutral varieties should be a priority. Although they would likely flower much less than ornamental dahlias, they could be grown and harvested earlier in the year. Tuber formation would also probably be greater with a longer season to bulk up.

Altering the balance of dahlia’s storage carbohydrates would be worthwhile. Because they are high in inulin, dahlias are unlikely to be used as a staple crop. Shifting the carbohydrate balance toward digestible sugars would not only make them sweeter and more nutritious, but also less likely to cause digestive upset when consumed in larger quantities.

21 thoughts on “Edible Dahlia (Dahlia spp.)”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

When will you have yellow gem for sale?

This fall, I hope, but there is no guarantee. This variety is infected with a virus that I have been trying to clean up.

My husband is mayan from todos santos cuchumatan in the guatemalan department of huehuetenango. They speak mam dialect and they eat the leaf. People from thete grow it in oakland ca. We live in lake county ca and have some in the yard but it doesn’t like the hot summer and our winters are a little too cold. They call it choonis. Thats my spelling of it.

Thanks Patricia – it is great to have the first hand information!

I gave a tree dahlia (Dahia imperialis) branch to a painting contractor for his wife to propagate. He told me that in his birth country (somewhere in Central America; I didn’t inquire), his grandmother eats the leaves of these plants. It’s good to have independent confirmation of his assertion.

I’ve been growing out a bunch of dahlias from Dandy and Unwin seed mixes. I’m getting ready to plant out the tubers again this spring, and I’m wanting to taste-test as I plant to weed out the nasty ones (some that we were eating this winter weren’t so nice, some were decent). My problem is that a lot of the clusters of tubers got separated so I can’t just taste one from a cluster and plant the rest if it’s good. Can I slice a sample from the base of a tuber to taste it without making it unviable? They seem pretty prone to rotting and I’m worried that damaged tubers wouldn’t grow… Thoughts?

I don’t think you will do any harm taking portions of some of the tubers. The cuts should heal over as long as the soil isn’t very wet.

Great information, I’ve wonders about the edibility of Dahlias.

Re: inulin and digestion – one factor with this prebiotic, we need the right balance of gut flora to utilize it. And some folks still have problems with inulin

Dr William Davis is a cardiologist, and wrote Wheat Belly after his mother died from heart disease.)

He has since become very interested in gut health and the human microbiome, leading him to research on Lactobacillus reureri, which was common until mid century, but is now rare in humans. Intriguingly, it was fist discovered by a German doctor – Reuter – in Peru, where many inulin rich tubers are grown!

For the last several months I’ve been making L rureri yogurt, using tablets from Biogaia and coconut milk, plus some inulin powder and sugar per his recipe. Tastes good and free of lots of extra stuff! I’m sensitive to dairy, it can be cultured on full fat dairy, and other probiotics can be used in the culture, for those who have trouble with inulin. I commonly add some maca, bee pollen, and fresh berries while they’re in season.

Dr Davis suggests keeping this culture to L reureri, and waiting to introduce more probiotics for a week or so, to let the microbiome adjust. He suggests making /using a range of probiotics foods and drinks, and using other yogurt as desired. (Undoctored.com)

“The first strain of Lactobacillus reuteri (L. reuteri) for human use, L. reuteri DSM 17938, was isolated in 1990 from the breast milk of a Peruvian mother living in the Andes. The commercial name is L. reuteri Protectis. Other human strains from BioGaia are L. reuteri ATCC PTA 5289 and ATCC PTA 6475. L. reuteri ATCC PTA 5289 used in oral health products was isolated from the oral cavity of a Japanese woman with remarkably good dental status and L. reuteri ATCC PTA 6475 was isolated from breast milk in Finland.” Biogaia website

Thanks for your great site and offerings!

Great leads – – Thanks Nadya !

I’ve read of one Dahlia grower who tasted his collection (60-80 varieties & species), claiming the tastiest ones were the yellow & red “Sunny Boy” and the brown & white “Akita”. They might make a good addition to the breeding program.

Thanks, Caesar! That is good to know.

Lubera a Swiss company have been breeding and selling dahlias specifically for edibility, I think the calked them deli dahlia. They even give taste notes of the varieties. I really wanted to order some this year with my Christmas money, but sadly due to Brext they are no longer shipping to us here in the UK.

Are the leaves edible too please.

I am thinking about growing these with children who may eat the leaves so it doesn’t matter if they taste nice -just so they are not harmful.Thanks

Yes, every part of the dahlia plant is non-toxic, although not necessarily enjoyable to eat. Of course, safety is always relative. Some people may be allergic or have sensitivities to plants that most people do not have any trouble with.

Thanks Bill

Here in Europe a big swiss company called Lubera sells different varieties of edible dahlias in pots. They also sell small yacon plants from tissue culture.

Hi, can you tell me if the flower petals from Dahlias are also edible?

Yes, every part of the dahlia plant is edible, inasmuch as it is nontoxic. Whether or not it is tasty enough to be edible is your call.

Decades ago, in the SF bay area of California, I found roasted dahlia bulbs as a coffee substitute. It was delicious. It soon disappeared from the market, and I have never seen any since. Has anyone tried this? I would be most interested in trying it again, but I have no dahlia bulbs, and cannot grow them in Boston.

I am wondering more about use of leaves than the roots. I often add a few dahlia leaves to salads. They have a rich green color and a fairly strong flavor. I haven’t cooked them, but wonder what the nutritional profile is.

I can’t say much about the nutrition of dahlia leaves, but they are certainly edible, if rather fibrous.