True Potato Seeds (TPS)

Overview

- Potatoes can be grown from true potato seeds (TPS) which are collected from the berries of the potato plant.

- Growing potatoes from true potato seeds is fun and you can discover some very good new varieties, but it is not as reliable as growing potatoes from tubers.

- Potato is a genetically diverse crop and the seedlings do not grow true. That means that every seedling grown from TPS is genetically unique and will produce tubers with different characteristics than the parent. Every potato plant grown from seed is a new variety.

- There are thousands of potato varieties with different colors and forms found in the Andes, but these types are a challenge to grow in North America because they do not form tubers until very late in the growing season. Andean potatoes are more readily available as TPS than as tubers.

- Growing potatoes from TPS is much like growing tomatoes from seed. The plants are started indoors and then transplanted to their permanent growing location.

- Most modern potato varieties are either partly sterile, poor at forming seeds, or both. If you want to save your own TPS, you will need to start with fertile varieties or with purchased TPS, which will usually produce much more fertile varieties.

- Some potatoes grown from true potato seeds will have higher than normal levels of glycoalkaloids, which make the potatoes bitter. You should discard any bitter varieties.

- Although true potato seeds carry much less disease than tubers, some diseases do infect seeds. For this reason, you should not import TPS from other countries.

If you don’t have time to read all of this right now, you can also get the basics in the Absolute Beginner’s Guide to True Potato Seeds.

About Potatoes

Introduction

This guide is a little bit different from the rest of the growing guide because it focuses only on growing potatoes from seed, rather than comprehensive growing practices for potatoes. You could fill a library with books written on everything from the history of the potato to laboratory techniques for the manipulation of its genome. There is no sense in rehashing topics that have been covered many times already, in depth, by people who are far more authoritative than I will ever be. So, I am not going to describe the characteristics of mass market potatoes or provide instructions for growing from tubers. Instead, I am going to focus in this guide on growing potatoes from true potato seeds (TPS) and evaluating, propagating, and maintaining what you produce. I will also discuss potato classification, because learning how to grow potatoes from true potato seeds will give you access to many more types of potatoes than you have probably been exposed to before.

Few gardeners grow potatoes from true seeds. For that matter, relatively few gardeners grow potatoes at all. They have never been a particularly popular garden vegetable in the United States and there are some good reasons for that. Firstly, much of the USA is marginal potato country. While Europe is overwhelmingly a potato climate, most of the USA is better suited to growing corn as a staple crop. Just two states, Idaho and Washington, produce the vast majority of potatoes in the country, with California, Colorado, North Dakota, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Oregon, and Wisconsin producing much smaller amounts. If climate change projections are correct, many of those states are likely to be less potato friendly in the future. The rest of the country may be too warm, too dry, or too humid in the summer for good potato production. Of course, we’re talking about commercial production, not gardens. In your garden, you may be able to grow good potatoes even under conditions that would never suit commercial scale growing.

Climate is not the only reason why potatoes don’t make the list of most popular garden crops. Another factor is price. Potatoes are cheap. You probably can’t grow potatoes more cheaply than you can buy them. Even if you can, it probably isn’t as decisive a win as it can be to grow crops like tomatoes, peppers, asparagus, or berries, which tend to be more perishable and expensive. The third thing that we might factor in here is that there has not traditionally been much difference between the potatoes available to farmers and gardeners. You can pick up any seed catalog and find dozens if not hundreds of different tomato varieties, most of which you will never find at the store. But the potatoes available to gardeners tend to be just the same varieties used in large scale growing. Most people probably don’t see much point in growing the very same potatoes that they can buy so cheaply at the grocery store. It is this last factor that you can really change when growing potatoes from true seeds. Growing potatoes from TPS gives you access to greater genetic diversity. You can grow potatoes that have much different colors, shapes, and flavors than you will find at the grocery store. You can also grow potatoes that may be better suited to your particular climate than the commercial varieties that are overwhelmingly adapted for the northern states.

Although the potato is a common crop, the types that most of us are familiar with are only part of a large range of varieties with different characteristics and uses. In North America, the potato is a commodity crop, meaning that it is priced and traded almost completely by weight, destined for processing, with little regard for the characteristics of varieties. Only a small part of the crop is grown for “fresh use.” Most people can identify four broad types of potatoes: russet baking potatoes, white and red boiling potatoes, and yellow ‘Yukon Gold’ type potatoes. In fact, there are dozens of varieties represented in each category, even including the supposed ‘Yukon Gold.’ The only potato variety name that most Americans recognize has been adopted as a category name and the yellow potatoes sold as ‘Yukon Golds’ are often not that variety at all.

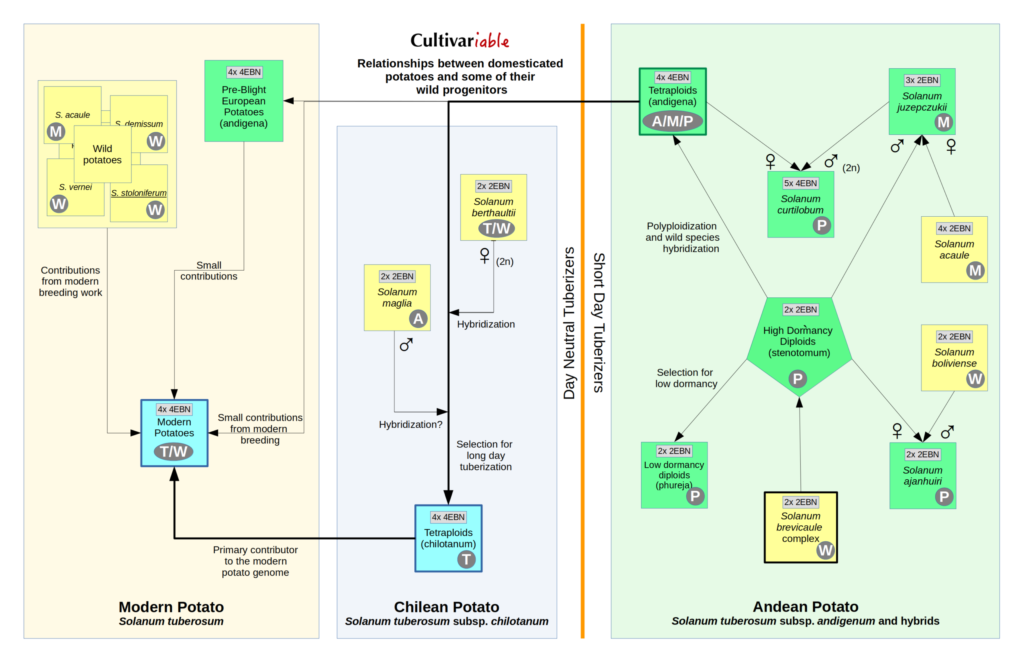

Almost every potato that you have ever seen at the grocery store comes primarily from progenitors of Chilean origin, a group of potatoes that were introduced to North America and Europe in the late 1800s, following the introduction of late blight. These Chilean potatoes, in turn, descended from a different domesticated group of Andean potatoes, which remain almost unknown in the rest of the world. Andean potatoes come in an amazing range of shapes, colors, and flavors, but the only way that most of us in North America will experience them is by growing them from true potato seeds. There are also many species of wild potatoes, most of which are rarely available as tubers. So, growing potatoes from TPS not only allows you to breed your own varieties, but also opens up the possibility of exploring the much wider range of colors, textures, and flavors that are possible with this crop.

Most people who have never grown a potato probably have given little thought to how potatoes are grown. The majority of the people I know can be divided into two camps: those who think that potatoes are planted from seeds and those who believe that there is no such thing as a potato seed. In fact, potatoes are usually planted from tubers but also can produce seeds. Potato is primarily a clonally propagated crop. We plant tubers, which are clones of the parent variety. A tuber is really just a modified stem, so when you propagate a plant from tubers, you are really doing the same thing as when you propagate a plant from stem cuttings. Potato tubers for planting are often referred to as “seed tubers,” which complicates discussion. I will not use that term in the rest of this guide; wherever you see the word “seed,” I am referring exclusively to true potato seeds. In general, you will need to use the acronym “TPS” to find additional information about growing potatoes from true potato seeds, since the seed tubers are widely referred to simply as “seed”. True potato seed is also sometimes called “botanical potato seed,” or even the rather redundant “true, botanical potato seed.”

Most people who have never grown a potato probably have given little thought to how potatoes are grown. The majority of the people I know can be divided into two camps: those who think that potatoes are planted from seeds and those who believe that there is no such thing as a potato seed. In fact, potatoes are usually planted from tubers but also can produce seeds. Potato is primarily a clonally propagated crop. We plant tubers, which are clones of the parent variety. A tuber is really just a modified stem, so when you propagate a plant from tubers, you are really doing the same thing as when you propagate a plant from stem cuttings. Potato tubers for planting are often referred to as “seed tubers,” which complicates discussion. I will not use that term in the rest of this guide; wherever you see the word “seed,” I am referring exclusively to true potato seeds. In general, you will need to use the acronym “TPS” to find additional information about growing potatoes from true potato seeds, since the seed tubers are widely referred to simply as “seed”. True potato seed is also sometimes called “botanical potato seed,” or even the rather redundant “true, botanical potato seed.”

Potatoes belong to the family Solanaceae, the same family as the tomato, pepper, eggplant, ground cherry, tobacco, petunia, and nightshade, among many others. If you have grown tomatoes and potatoes before, you have probably noticed the similarities between the two species. Unlike tomatoes, which have small flowers and large berries, potato flowers are large and the berries are small. Although they are rarely seen in hot or dry climates, potato plants produce both flowers and berries that look like small, green (or occasionally red or purple) tomatoes. Each berry contains up to about three hundred true potato seeds, although many varieties produce much smaller amounts. These berries are sometimes called “seed balls,” although that is now a pretty dated term.

The range of potato plants that even most experienced gardeners have seen is pretty small. There are roughly 50 varieties that are commonly grown in North America and they fall mostly into the category of russet baking potatoes, red and yellow boiling potatoes, and fingerlings. If you grow potatoes from true potato seeds, you will discover that potato plants can grow up to five feet tall, that some of them have partly purple foliage, that they have flowers of many different colors, and that the tubers have a range of skin and flesh colors that extends well beyond the white, yellow, and red potatoes most frequently seen in grocery stores. Growing potatoes from seed can be a source of both joy and frustration because, in addition to the wide diversity of form and flavor, you will also encounter problems that are never seen in commercial potatoes.

There are thousands of varieties of potatoes, belonging to four domesticated species. The majority of them are only grown in their native region in the Andes, where there are about 3,000 extant varieties. The potatoes used in the rest of the world have emerged from a relatively narrow genetic bottleneck as a consequence of breeding them for performance in other climates and with traits suitable for industrial agriculture. So, we normally see only a very small selection of potatoes that were bred from a relatively small number of parents and that were selected to suit the sensibilities of modern agriculture. In addition to the four domesticated species, there are approximately 100 species of wild potatoes as well, which are found from Utah in the north to Argentina in the south, with centers of diversity in Mexico and the central Andes.

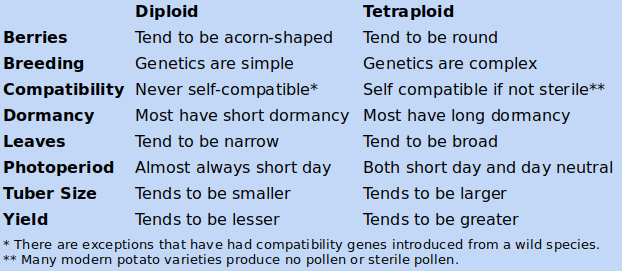

Potatoes primarily come in two different genetic arrangements: tetraploid and diploid. Outside the Andes, diploid potatoes are virtually unknown. The potato of commerce is tetraploid, bearing four copies of each chromosome, resulting in a sort of built-in hybrid vigor that typically allows them to grow larger and yield more than diploids. Potatoes are outbreeders and experience inbreeding depression. As a result, they do not grow true from seed. Every potato plant grown from TPS is genetically different. Varieties can only be maintained by replanting the tubers. Therefore, the primary use of true potato seeds is the creation of new varieties.

Almost all mass market potatoes outside the Andes are tetraploid. Tetraploid potatoes are usually larger, higher yielding, and boring. No, that’s an exaggeration. Actually, there are a great many exciting tetraploid potatoes… mostly in the Andes. The potatoes of commerce in the rest of the world are big and uniform but not nearly as fun as the wide diversity of shapes, colors, and flavors that you can grow from true potato seeds. This is a matter of opinion, of course, but even a cursory examination of Andean and modern potatoes reveals that their selection was driven by fundamentally different values. Tetraploid potatoes are further distinguished by having the ability to self-pollinate in some cases.

Diploid potatoes are almost exclusively grown in the Andes and there are no mass market diploid varieties in North America (there are a few in Europe and Japan). Even in the Andes, they comprise a fairly small percentage of varieties; most Andean potatoes are tetraploids. Diploid potatoes are small and usually have lower yields than tetraploids, but they compensate for this with a great diversity of skin and flesh colors. Many of them have flavor that is superior to commodity potatoes. In addition to the tubers, the plants are typically smaller and have narrow foliage compared to tetraploids. The seeds are usually smaller than those of tetraploids as well (Simmonds 1963). Diploid potatoes are self-incompatible, so every variety is a hybrid.

With true potato seeds, you have the opportunity to explore all of the varying traits of the potato and you can choose those that are most important to you. When you grow potatoes from true potato seeds and then select your favorites to propagate, you are engaged in plant breeding. You are forming the latest link in a chain that goes back ten thousand years or more, to the first potatoes taken from the wild.

Characteristics of True Potato Seeds

True potato seeds collected here have averaged 2,317 per gram across all domesticated and wild varieties. They range from as small as 4440 per gram to as large as 880 per gram. The size of seeds and number per berry will vary with conditions. The more compatible pollen and pollinators that are present, the greater the number of seeds per berry and the smaller the seeds will be. A potato flower can contain 1200 ovules, each of which has the potential to be pollinated and become a seed, but it is very rare to find berries that contain even 600 seeds, half of the potential maximum. The more heavily domesticated that a potato variety is, the fewer seeds that it tends to produce and the larger they tend to be, although there is a great deal of variance even within closely related varieties. Wild potatoes tend to produce more berries with higher seed counts than domesticated varieties. Among domesticated varieties, landrace diploids from South America tend to produce the highest numbers of berries and seeds and have correspondingly smaller seeds. Varieties with impaired sexual reproduction tend to produce the largest seeds, presumably as a consequence of the small number of seeds per berry.

Seeds range in color from off-white to dark brown. Seed color is influenced by the color of the embryo within the seed and staining from pigments in the berry and the maturity of the berries from which they were collected. Seeds from berries that have fully ripened tend to be larger and darker than those collected from berries that are not yet ripe. In addition to differences in color, there can be a difference of as much as 60% in seed weight between seeds extracted at the earliest viable stage (five weeks post flower drop) and seeds extracted from berries that have been allowed to naturally drop from the plant at around ten weeks.

Large Scale Commercial Experiments with TPS

Most sources of true potato seeds, like Cultivariable, cater primarily to small breeders and hobbyists. The seeds are genetically diverse and growers expect to make selections from the resulting plants to grow the following year, rather than immediately grow a crop for market. Once people become comfortable with the process of growing potatoes from seed, they often wonder why it isn’t done on a larger scale. Why don’t farmers grow entire crops from seed? While the main reason is probably just the considerable extra work involved in raising a crop from seed, uniformity is also a big challenge for commodity potato growers, who have to meet fairly strict criteria to sell a crop a top price.

There have been some experiments with tetraploid potatoes that have been inbred sufficiently to produce a fairly uniform crop. The Soviet Union did some work on this, starting in the 1970s and some of the varieties are still available in eastern Europe. In the USA, the Pan American Seed Company introduced the TPS variety ‘Explorer’ in 1981. Explorer appears to have mostly disappointed growers, producing small although relatively uniform tubers, but with unpredictable maturities. It was off the market before the decade was out. Bejo seeds has introduced a number of “F1 hybrid” varieties, including ‘Catalina’ and ‘Zolushka’ in the early 2000s and a new variety called ‘Clancy‘ in 2018. I have grown Zolushka and found basically the same results that were described for Explorer. The tubers are pretty uniform, but underperform most white potatoes that you would plant from tubers, and the plants vary considerably in form and maturity. I presume that mass market TPS varieties will continue to improve though.

Breeders of so-called “uniform” tetraploid TPS potatoes are up against the crop’s intrinsic genetic diversity. By the time you have done enough in-breeding, you usually have a potato is is neither robust nor very interesting. Home gardeners who are willing to go to the trouble of growing potatoes from seed probably prefer diversity to uniformity. Demand for uniform TPS appears to be limited mostly to countries that lack a certified seed system, where TPS may be the most affordable disease-free alternative to saved seed tubers. These mass market TPS varieties have done poorly so far, but it would be great if one came along and did well, as that would introduce more people to the practice of growing potatoes from seed.

There is now a lot of enthusiasm for breeding diploid TPS varieties. This is probably more feasible than breeding a uniform tetraploid, but the barriers to inbreeding in diploid potatoes have been difficult to overcome. Researchers are just starting to make progress identifying the genes that make diploid potato inbreeding most challenging, so we will probably start to see more progress. Nevertheless, I suspect that it will be a while before we see a uniform TPS variety that can compete with seed tubers. Even if we get some high quality, uniform, F1 TPS varieties, I wonder whether or not this will be a practical choice for large scale farmers in countries with an established certified seed tuber system. It is certainly a lot easier to start potatoes from tubers than seeds, particularly at scale. Perhaps these new diploids will be first targeted at home growers, which would be a very interesting development.

Potato Classification

You are probably familiar with the scientific name for potatoes, Solanum tuberosum, but this is, in fact, just one of several species of domesticated potatoes. The scientific taxonomy of cultivated potatoes has been consistently updated and refined over the past two hundred years. This is good insofar as it shows the progress of our understanding of the evolutionary relationships between varieties. It is, however, rather confusing for the amateur potato breeder, because the potato literature is filled with references to outdated systems.

The two main classification systems used in the potato literature of the past thirty years divide the different potato groups into either nine species (Hawkes 1990) or four species with subdivisions (Spooner 2014). There is ongoing debate about which system is better supported and, unfortunately, this has resulted in a schism. The Hawkes system is still widely used, particularly in South America, but the Spooner system has been adopted in North America. They are not used consistently in modern work; for example, while the USDA gene bank generally uses the most recent taxonomy, the International Potato Center (CIP), still uses the old species designations. Unfortunately, even if the world does eventually settle on a single system, nobody is going to go back and revise all of the books, research, gene bank identifications, and other material that relies upon the previous classification systems. You will benefit from familiarity with both systems of classification.

| Hawkes Classification (CIP Standard) | Spooner Classification (USDA Standard) |

| Solanum phureja (2x) | Solanum tuberosum group Andigenum (2x,3x,4x) |

| Solanum stenotomum subsp. goniocalyx (2x) | |

| Solanum stenotomum subsp. stenotomum (2x) | |

| Solanum x chaucha (3x) | |

| Solanum tuberosum subsp. andigenum (4x) | |

| Solanum tuberosum subsp. tuberosum (4x) |

Solanum tuberosum group Chilotanum |

| Solanum x ajanhuiri | Solanum ajanhuiri |

| Solanum x curtilobum | Solanum curtilobum |

| Solanum x juzepczukii | Solanum juzepczukii |

Historical Divisions of Cultivated Potatoes

Tuberosum

S. tuberosum subsp. tuberosum or S. tuberosum, Tuberosum group.

Tetraploid. The modern potato, which probably originated in coastal Chile as a result of selection among andigena type potatoes for long day tuberization. This group of potatoes was introduced to Europe about 150 years after andigena types and was bred intensively following the destruction of many of the existing andigena cultivars by late blight.

Andigena

S. tuberosum subsp. andigenum or S. tuberosum, Andigenum group.

Tetraploid, originating probably from a natural hybridization between a stenotomum potato and a wild relative (Grun 1990). Andigena potatoes are the immediate ancestor of Chilean potatoes. Their main distinction from modern and Chilean varieties is that they have short day tuberization. Size and yield are generally smaller than modern potatoes. They are considerably more diverse though, with a wide range of colors and shapes. Taste is often superior to that of modern potatoes. Unfortunately, many of them are quite vulnerable to late blight, because the late blight pathogen was not present during their evolution. This was the group of potatoes originally introduced to Europe, before late blight developed and made it infeasible to continue growing them. Only a few examples of pre-blight Andean-derived European potatoes still exist, of which the Irish variety Lumper and the English variety Myatt’s Ashleaf are the most common.

Stenotomum

S. stenotomum or S. tuberosum, Stenotomum group.

Stenotomum potatoes are diploids. Unlike the Phureja group of diploids, they have dormancy. They are grown at higher elevations in the Andes and many have some frost resistance (NRC 1989). Stenotomum tubers tend to be long, often with an irregular surface, and colors are primarily white, red, or purple. Frost resistance and dormancy make this group of potatoes particularly interesting for breeding for short season climates. Stenotomum includes what was previously known as S. goniocalyx, commonly known as papa amarilla, a group of small potatoes with yellow skin and flesh, known for their particularly rich flavor. Stenotomum is thought to be the earliest of the domesticated potatoes, from which all other Andean domesticated potatoes descended.

Phureja

S. phureja subsp. phureja or S. tuberosum, Phureja group.

Phureja potatoes are diploids. Few have any significant dormancy; very shortly after the tubers mature, they begin to sprout again. This is a useful trait in the warmer eastern side of the Andes, where they are grown between 7000 and 8500 feet. Because frosts are rare at these elevations, there can be two or three crops per year. Lack of dormancy is generally an unsuitable trait for growing in North America, where the tubers can be exhausted in storage before the weather is suitable for planting, although there are techniques that can be used to grow such potatoes successfully, particularly in relatively mild climates like the maritime Pacific Northwest.

Phureja potatoes are usually small, two to three inches (5 to 7.5 cm) in diameter at the most, but they are colorful, often have unusual shapes and deep eyes, and have excellent flavor. They also often have superior disease resistance. They can be hybridized (with a low success rate, but one still manageable by amateurs) with tetraploid Solanum tuberosum, usually producing tetraploid progeny (Grun 1990). The tetraploid progeny sometimes have good dormancy. They are grown at lower altitudes in the Andes and do not exhibit frost tolerance. Phureja potatoes are thought to have been bred from stenotomum potatoes, with the goal of eliminating dormancy (NRC 1989). Hundreds of varieties exist in the Andes.

Modern Divisions of Cultivated Potatoes

As noted earlier, modern genetic analysis is wiping away all of the historical categories. I introduced them first because there is such a huge body of literature that uses them that you will probably continue to find them more useful than modern classification for a long time to come. Modern classification lumps the four categories from the previous section into two cultivar groups under S. tuberosum: Andigenum and Chilotanum. There are also additional species recognized for the higher polyploids, but I’m sticking to the basics in this guide. See Spooner (2007) for a more detailed treatment.

Andigenum Group

This is the group of Andean potatoes and includes everything that was previously included in the Andigena, Stenotomum, and Phureja groups. This includes diploid and tetraploid varieties. Most are short day tuberizers.

For more information about Andean potatoes, check out our Andean potato guide.

Chilotanum Group

This is the group of tetraploid potatoes of Chilean origin. This includes most modern potatoes, although modern potatoes are now commonly hybridized with more distant relatives. Most of them are day neutral types.

There are other groups of cultivated potatoes and roughly 100 edible and non-edible wild relatives, but those are outside the scope of this guide.

Diploids vs. Tetraploids

There is quite a bit more to potato ploidy than I am covering here. Understanding the nuts and bolts will become a lot more important to you as you do more intentional breeding and produce your own true potato seeds from controlled crosses. But, knowledge must be built one step at a time and this section will get you through the basics.

Diploid potatoes are more straightforward for breeding because they have only two sets of chromosomes, meaning only two copies of each gene, called alleles. This makes it much easier to determine the genotypes of varieties and to plan crosses more effectively. Despite that, the vast majority of varieties in the world, and almost all of the modern varieties, are tetraploid. Tetraploids have four sets of chromosomes, so four alleles of each gene, which doubles the genetic complexity and makes it much more difficult to predict inheritance of traits. If we were encountering the crop for the first time today, with the benefits of all our accumulated knowledge, we might choose to adopt diploid potatoes as the foundation of further breeding efforts, but the introduction of the potato to Europe was not planned. It happened gradually, from a few separate introductions, and most of the early breeding was done by people whom we would now consider amateurs. They had little knowledge of the potato because that sort of knowledge simply wasn’t available. They had to learn from experience.

There are other reasons as well. As a rule, tetraploid potatoes are higher yielding and have larger tubers. While there is some overlap, the yield potential in tetraploids will probably always be greater than that of diploids. Throughout the plant kingdom, polyploids (any level of ploidy greater than diploid) usually are larger than diploids. Polyploids have more copies of each gene, so they make more proteins. This causes them to have larger cells and the larger cells tend to translate into a larger overall plant with a greater yield.

There are other reasons as well. As a rule, tetraploid potatoes are higher yielding and have larger tubers. While there is some overlap, the yield potential in tetraploids will probably always be greater than that of diploids. Throughout the plant kingdom, polyploids (any level of ploidy greater than diploid) usually are larger than diploids. Polyploids have more copies of each gene, so they make more proteins. This causes them to have larger cells and the larger cells tend to translate into a larger overall plant with a greater yield.

Another significant problem is that diploids tend to be short day tuberizers; in North America, they don’t begin to form tubers until fall. This would be a serious problem for potato growing in most areas of the country. There is some variability in this trait to select from, so this problem is often overstated, but it does complicate the breeding of diploid varieties. Many diploids also have no dormancy, which is a problem similar in scale to the short day problem. There aren’t many climates in North America where potatoes without dormancy will overwinter easily.

There is a small group of diploids, previously classified as S. stenotomum, that have dormancy. They only need to be selected for longer day length tuberization in order to have a breeding population suitable for higher latitude growing. It isn’t clear why more work hasn’t been done with these varieties. One problem is that they are not particularly diverse, with only a small number of extant varieties. Working with high dormancy diploid potatoes to select varieties that can grow well in North America would probably be a good project for amateur and freelance breeders. Once varieties are selected that tuberize in longer days, they could then be crossed with the more diverse pool of low dormancy diploids for further development.

Growing Potatoes from True Potato Seeds

You have two possible routes to starting your adventure in growing potatoes from seed: you can grow plants from tubers and use them to produce TPS or you can obtain seeds to start with. If you do not have an existing collection of tubers to work with, I recommend starting with true seeds, as it will save you time, have a far lower risk of introducing potato diseases, and should give you much greater genetic diversity to work with. You should also consider that many modern varieties are male sterile. They will set seed if pollinated by another variety, but they will also transmit the male sterility to the next generation. This is another good reason to start from seeds that have been produced by a population that does not include male sterile varieties.

Why Grow Potatoes from True Potato Seeds?

Growing potatoes from TPS adds work and complexity to what is normally one of the simpler plants to grow in the garden. Toss a few tubers in the ground and a few weeks later, you should have thriving potato plants. Growing potatoes from TPS is similar to growing tomatoes from seed, which is a task that many people outsource by buying starts. So, why go to the effort?

As a Supplement to Tubers

Have you ever thought that you would like a potato a little bit different than those available for planting? Maybe you need resistance to a particular pest or disease. Maybe you like the flavor of a variety but wish that it produced a bit better. Maybe you would like to experiment with colors and sizes that aren’t commonly available. If so, you could consider breeding your own potatoes from true potato seeds. Once you find a potato that you like, you can just keep replanting the tubers every year. Over time, you can build a collection of your own varieties, unique to your garden. When you begin to grow potatoes from TPS and selecting the ones that you like best, you are taking the first steps toward breeding your own varieties.

Instead of Tubers

Do you have problems with potato diseases, but hate buying certified tubers? Do you like to experiment more than you value a predictable harvest? Would you rather have a bowl full of tubers of all shapes, sizes, and colors, rather than uniform potatoes that look just like what you can buy at the store? If so, you might forget about planting from tubers entirely and just grow from true potato seeds every year.

Although I now keep a lot of tubers for continued breeding, for several years, I grew potatoes only from seed. It was a surprisingly successful experiment! We never lacked for potatoes to eat. Many of the plants were low yielding, but many were also high yielding, so it balanced out. Production was about the same as I achieved growing commercial potatoes from tubers. I rarely found inedible, bitter potatoes, although there were a few that tasted pretty bad. It should be noted that I live in a very potato friendly climate, so results may not be so good elsewhere, but I definitely think that this is an experiment worth trying.

Climate Tolerance

Potato plants flower and set seed most readily in cool, humid conditions. This is a commonality of Andean crops, which originated in cool, tropical highlands. In potato, higher temperatures reduce or completely suppress flowering and pollen production. The viability of whatever pollen that is produced is also reduced at higher temperatures. Some varieties will set seed even in hot, dry conditions, but the widest range of varieties will flower and fruit in maritime climates.

In many climates, it will be much easier to start with TPS produced by someone growing in more favorable conditions. Once you have seedlings with a wide range of characteristics, you are likely to find a few that set seed in your climate more readily than the commodity varieties. You can then save seeds from those plants and you will be on your way to a better adapted potato for your location.

Photoperiod

One of the great breakthroughs that allowed the potato to become one of the world’s staple crops was the development of varieties that are day length neutral. In the Andes, almost all potatoes are short day tuberizers; they don’t begin to form tubers when there are more than roughly twelve hours of daylight. This is not an impediment near the equator, where day length changes very little over the course of the year, but at higher latitudes, short day varieties don’t begin to form tubers until the end of September, by which time frosts are approaching in many areas.

When you grow mass market varieties of potato, you are guaranteed that they will be day neutral, but when you grow potatoes from true potato seeds, particularly if they are Andean varieties, it is very likely that they will turn out to be short day plants. In colder climates with a short growing season, you will probably want to discard all of the short day plants, since the odds of producing tubers are low. However, in climates with a long growing season, short day plants can actually turn out to be good performers. They often produce very large vines and, although they form tubers late in the growing season, they can leverage that huge plant to form heavy yields quickly.

Flowering is also influenced by day length. In general, long days are most suitable for potato flowering. True potato seeds also have stronger dormancy when produced under long day conditions (Taylorson 1982). For this reason, TPS produced at higher latitudes is best stored for a year or more before sowing, although there are ways to improve germination in dormant seed, discussed below.

Storage

True potato seeds are typically long lived. According to one study, they retain good germination for at least fifteen years at 70° F (20 C), showing almost no reduction in germinability (Barker 1980). My results have not been as good as those indicated by the research and I expect to see significant reductions in germination from potato seeds stored at room temperature after five years. What is the difference? Possibly temperature variation. There is a big difference between “room temperature” of 70 degrees in a temperature controlled storage facility and an average room temperature of 70 degrees in your house, which might easily range from 50 to 90 degrees over the course of the year in many climates, or even more if you store your seeds in an out of the way place like a porch or attic. My rule of thumb is that you lose 90% after 5 years and the remaining 10% over the following five years. So, if you have a lot of seed, you can probably still get seedlings after 10 years, but if you have 100 seeds or less, the odds are stacking up against you after 5 years. With certain varieties or in more favorable climates, you might still get very good germination after five years, but you shouldn’t count on it. By reducing storage temperature to 40° F (5C) or less, and preferably all the way down to 0F (-18C), potato seeds may retain acceptable germination for 50 years or more. If you want to store TPS for long periods of time, I recommend that you fully dry the seeds, package them in a resealable plastic bag with a silica desiccant packet at least 10% the weight of the seeds, and store them in your freezer.

Towill (1983) summarized data gathered at the USDA Potato Introduction Station for both domesticated and wild potatoes. Stored at a temperature of 1 to 3 C (about 34 to 37 F) after drying to 5% humidity, the seeds of domesticated species showed very little loss of germination over 27 years. Wild potatoes were less consistent, but retained good germination over similarly long periods with a few exceptions: S. berthaultii dropped from 80% to 4% over 23 years, S. andreanum from 90% to 12% over 12 years, and S. stoloniferum (as S. fendleri) dropped as much as 100% to 28% over 21 years. Some species showed increases in germination over similar periods.

Exposing true potato seeds to high temperatures has significant effects on both dormancy and lifespan. Pallais (1995) found that seeds stored at high temperature and higher moisture content lost dormancy within four months and germinated at 88%. However, when dormancy is broken by exposure to high temperature, seed life is reduced. High temperature storage may be useful when there is a requirement to sow seed shortly after it is collected, but if there is a requirement to store seed for longer periods, it should be stored dry and cold.

Planting

In Brief

- Sow true potato seeds six to eight weeks before your last frost (at the earliest) or intended date for planting out.

- Press the seeds into the surface of your potting soil and cover by about 1/8 of an inch.

- Water thoroughly once with room temperature water and do not water again until the soil begins to dry out.

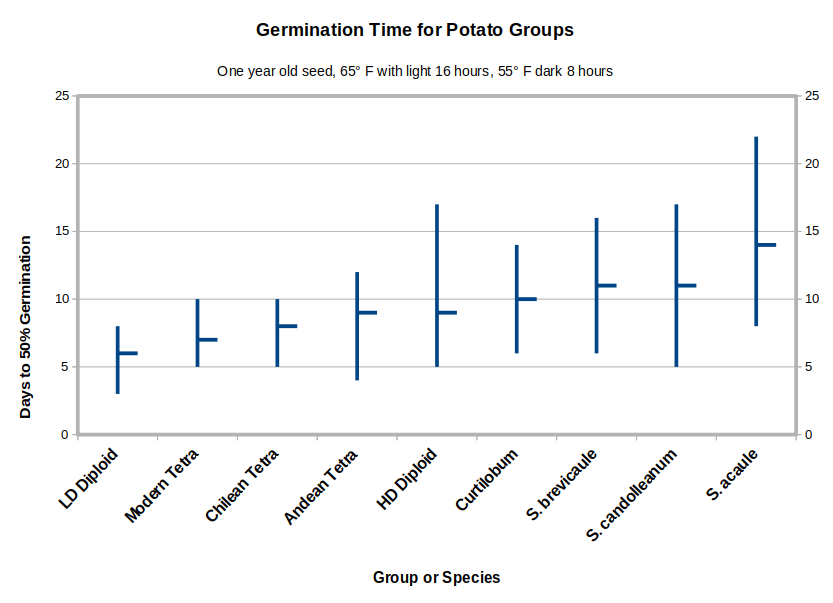

- Keep the temperature at about 65° F constant or alternate between 65° F day and 55° F night.

- Under the recommended conditions, expect to seed the first seedlings emerge in 7 to 10 days.

- Keep seedlings under strong lights for 14 to 16 hours per day.

- When seedlings are 4-6 inches tall harden off and then transplant to final location.

- Plant hardened seedlings into a hole or trench eight inches deep, backfilling to leave only the top set of leaves exposed.

- Fill the hole or trench to soil level as the seedling grows.

True potato seed is a fickle creature. Some germinate easily, in a short amount of time and with good uniformity. With others, you will be certain that the seeds were duds, only to have a seedling pop up a month later, and then another in a couple of weeks, followed by three or four in a flush, and then a long waiting period again. In some cases, the reason is genetic. In others, it is environmental. True potato seeds are covered in germination inhibitors and if the seeds are insufficiently cleaned, they can remain to interfere with your seed starting. Also, these substances break down over time, so fresher TPS often has more irregular germination than old seed.

True potato seed that is less than one year old is considered to be dormant and germination is more difficult than in older, non-dormant seed. Some varieties like conditions a little warmer and some a little colder. Some are just less domesticated and are holding onto the risk hedging strategy that is present in most seeds of wild plants; spreading germination over a long period ensures that at least some will grow under favorable conditions. Pallais (1995) found that dormant seed will germinate readily at 50 to 68 degrees F (10 to 20 C), but will only germinate at warmer temperatures once dormancy has been broken. If you can’t rely on your seed starting conditions holding in this range, then you would be better off storing fresh seed for a year before planting.

Sowing

Start true potato seeds indoors about six to eight weeks before you will be ready to plant them. If your growing conditions will be on the warmer side, six weeks should be fine and, if conditions will be on the cooler side, eight weeks is better. In that time, you should be able to produce seedlings that are about five inches (12.5 cm) tall and ready for transplant to the field. You really don’t need to rush to start TPS in most climates. If you start eight weeks before your average last frost, then some years will be colder and you will struggle to keep the seedlings in good condition until they can be transplanted. Unless you are in a very short season climate or one with scorching summers, you might as well give yourself a few weeks of leeway. I think that starting too early is one of the most common mistakes made when growing potatoes from seed. Once the seedlings are eight weeks old, you need to move fairly quickly to get them transplanted to the field as any with early maturities will begin to form tubers and further growth is limited once tuberization begins. Sowing as soon as frosts end may be important in hot summer climates, where you want the plants to be able to grow in cooler spring weather. In a cool to moderate summer climate, you can start potatoes from TPS as late as August and still produce a crop.

Press seeds into the surface of your medium (any soil or soilless medium is fine) and then cover just barely with a little bit of fine material. You don’t want much more than an eighth of an inch of soil cover. Another way to get the right depth is to sprinkle seeds on the surface of the soil and then tap the pot until the seeds disappear. Potato seed germination is inhibited by light, so it is important to cover them, but the seedlings are fairly weak and cannot push their way through a thick layer of soil. Keep the surface of the soil moist until you see seedlings beginning to emerge. At that point, you have two choices: you can prick out the seedlings and transfer them to another container or you can continue to grow them in the original containers. If you don’t transfer them, withhold water, allowing the surface of the soil to dry out before watering again. I prefer the first method because the conditions necessary for good germination and the conditions necessary for maintaining seedling health aren’t exactly the same. Most people don’t do this and still have good results, particularly if they perform two transplants (see below). Seedlings will usually perform best at temperatures between 60 and 70° F (16 to 20 C), but will tolerate a wider temperature range as they become established. Under the recommended conditions, you will generally see the first seedlings emerge in 7 to 10 days. If your conditions are a little colder, it can take longer. Germination time is controlled by many factors, so emergence can be much slower in some cases.

Keep seedlings under strong light. Potatoes evolved in the Andes, where light is intense due to the high elevation. At sea level, particularly during often cloudy spring conditions, it will be hard for them to get enough natural light. About five days after sowing, I put them under lights, so that the seedlings will have light as soon as they emerge. Standard fluorescent tubes must be kept about two to four inches (5 to 10 cm) off the tops of potato seedlings to provide sufficient light (the more bulbs per fixture, the higher they should be). Lights will increase the temperature around the plants, so you should keep a thermometer near the seedlings to check how much difference the lights make. Adjust your room temperature accordingly. More intense lights can be kept further from the seedlings. We use 8 bulb, 54 watt T5 fluorescent lamps, hung about 24 inches above the tops of the seedlings. Spacing for high intensity LED fixtures should be similar. The daily lighting period should be at least 14 hours; I prefer to use 16 hours on and 8 hours off, in most cases. In general, you can’t give potato seedlings too much light, but you can easily give them too much heat if you aren’t paying attention. When light drops below 14 hours, and particularly below 12 hours, you will start to see plants that tuberize early due to the short day photoperiod. That is generally not something that you want, since it will limit the growth of those plants.

Outdoor and Direct Sowing

True potato seeds can also be started outdoors under natural light. In northern regions with cool springs, this is best done a little later in the year. I start TPS outdoors in pots beginning in June. While you can direct sow (plant seeds directly in the ground), the total rate of seedling germination and survival is usually pretty low. Seedlings are small and fragile and losses to weather and pests tend to be very high. Seeds are better started in pots or seedling beds. A raised seedling bed will provide a little more soil warmth early on, which aids in germination. You can also run a heater cable in a seedling bed, which will help if you are trying for an early batch of seedlings in a chilly climate.

When direct sowing, wait until the soil temperature is reliably reaching 70 degrees during the day. I recommend soaking the seeds in water for a day before you sow to ensure that they are ready to germinate. Because potato seeds are planted shallowly, they may have difficulty taking up enough water to germinate if you don’t soak them. Sow seeds on the surface of the soil and then press down with your hands. Sow very heavily – 10 to 100 times as much seed as you would use under controlled conditions. In my most successful direct sowing experiments, I used one gram of seed per 32 row feet, which translates into about 1000 seeds to get 32 mature plants. That would be much too wasteful for purchased seed, but if you are able to produce your own seed, you will probably have more than enough. If you are experiencing dry conditions or wind, it may help to cover the seeds with a board for three or four days to help them retain moisture.

Improving Germination

You can potentially improve germination of true potato seeds in the following ways:

- Imbibition (soaking the seeds)

- Temperature alternation

- Treating with gibberellic acid (GA3)

- Supplementing with activated charcoal

For improved germination, you can soak seeds in room temperature water for 24 hours before sowing. This ensures that the seeds receive enough water to imbibe properly and at a temperature where they have the necessary metabolic activity to do so. In soil, the seeds may not receive enough water, particularly if they are surface sown. Lower temperatures also reduce the rate at which the seeds take in water, so the soil may dry out before they have imbibed enough. Germination time seems to naturally vary among different groups and species, so there is a limit to how much you can improve it. Low dormancy diploids and modern tetraploids are typically very quick to germinate, while more primitive groups and wild species tend to be slower.

The optimum constant temperature for true potato seed germination is about 60° F (16 C) (Lam 1968, Gallagher 1984, others). Alternation between 12 hours of 65° F (18 C) and 12 hours of 55° F (13 C) is more effective at germinating dormant seed (Lam 1968), although some wild species germinate poorly when the temperature is not constant (Bamberg 2018). At 60° F, true potato seeds of most domesticated varieties begin to germinate within ten days. They may germinate uniformly, with most of the seedlings emerging by the twentieth day, or you might get one seedling each week for months, known as “trickle germination.” If the ambient temperature is significantly lower than the range above, I recommend starting TPS over a thermostat controlled heating pad in order to achieve uniform temperature. In general, the more uniform the daytime and nighttime temperatures, the more uniform the germination is. When the temperature drops significantly at night, germination can be slowed substantially.

Germination can also be greatly increased by exposing the seeds to gibberellic acid (GA3). A 24 hour soaking in 50 ppm GA3 can produce more than 90% germination at 60° F (Lam 1968). A 24 hour soaking in 2000 ppm GA3 will break the strongest dormancy (Simmonds 1963) and this level is recommended by the USDA Potato Introduction Station (Bamberg 2017b). (A 50 ppm solution is 50 mg of GA3 dissolved in 1 liter of water and a 2000 ppm solution is 2 grams dissolved in 1 liter of water. Converted to more common and smaller amounts, for one cup of 50 ppm solution, use 12 mg of GA3 and for 2000 ppm solution, use 474 mg. Typically, you would first dissolve the GA3 in a small amount of rubbing alcohol and then mix that into the water, because GA3 is much more soluble in alcohol than water.)

Adding activated charcoal to the growing medium may also improve germination. Bamberg (1986) also found that it substantially improved and hastened germination in domesticated true potato seeds, but had a relatively small effect on germination in wild potato species. The study was done in Petri dishes, so it isn’t clear what level of supplementation might be effective when growing in soil.

I wouldn’t hesitate to use GA3 or activated charcoal to germinate irreplaceable seed, but I think it is worth considering whether regular use of supplements might introduce dependence. When breeding plants, I try to avoid using techniques that I don’t intend to employ permanently.

The First Year

You can treat seedling potato plants like any other potato, growing them out to full size plants and taking a normal harvest. To do this, you will need to undergo at least one properly timed transplant. Because seedling potato plants don’t have a tuber to draw on for reserve energy, they tend to be a bit more delicate than tuber grown plants. You will need to pay close attention and make sure that they get enough water and don’t have too much weed competition. Once the plants are well established, they are as tough as any other potato plant. Many people claim that it is not possible to get a full yield from seedling potatoes, but I think this is the result of insufficient hardening of the seedlings, mistimed transplant, or difficult growing conditions. It took some practice, but I routinely get full yields from first year plants.

Alternatively, you can grow your TPS seedlings in small pots for the first year. The pots will limit the size of the plants and help to encourage earlier tuberization unless they are short day types. Pots require less attention to hardening and transplant timing, so they are more forgiving. You will get a small yield of mini-tubers which can be planted out in the field directly the following year with much less care than is required for seedling plants. This is a technique that I use often, particularly if I am searching for particular traits in the tubers. This allows the space-efficient screening of large numbers of seedlings. On the other hand, if you aren’t looking for easily identifiable traits in the tubers, you then have to wait an extra year before making your first selection.

Transplanting

You can transplant once or twice. There are advantages and disadvantages to both methods. Whichever way you choose, allow the soil to dry out in between watering enough that it begins to shrink away from the walls of the container, but not so much that the seedlings wilt. Water from the bottom. You should water just enough that all of it is taken up into the containers. Don’t let the plants sit in a puddle. Managing wetness is crucial in avoiding damping off. A little water stress causes potatoes to form more extensive root systems, which is a big benefit when you transplant to the field (Wagner 2011).

Initial Transplant

Doing an initial transplant is optional, but can produce superior results and usually makes your life easier when transplanting to the field. Prick out the seedlings and plant into small cells in flats. This forces the seedlings to produce compact root balls (Wagner 2011). Although you can also transplant them into undivided flats, or containers of any sort, cells avoid the problems of spreading, tangled roots that result if you sow in open flats.

You can also transplant into a seedling bed if you have a greenhouse or live in a suitably mild climate. This is my preference. I plant seedlings in a bed with a six inch spacing in all directions. The root ball is not nearly as compact as those of plants grown in containers, but because the plants are not entangled, you can easily pull out the whole, fist sized root balls for transplanting to the field.

Field Transplant

Once your seedlings are about four inches (10 cm) tall, you should begin hardening them off. You can find an unlimited number of methods for hardening off, but the main idea is that you will gradually introduce the seedlings to outdoor conditions. I like the doubling method: one hour outside the first day, two hours the next, then four, eight, and sixteen hours. After that, the plants are ready for transplant.

If you chose not to do an initial transplant, then your seedlings will be crowded together and preparing them for field transplant will take some work. This involves a lot of disentangling and usually some losses. The easiest way is to soak each container in water for about an hour and then use a hose to spray the wet soil off of the roots. You can then pull apart the seedlings and plant them in the field.

You should transplant into holes or trenches about eight inches deep and backfill so that only the top set of leaves is exposed. If your seedling reaches the top of the hole or trench, you are done. If it still has some growing to do to reach ground level, fill in as it grows, always keeping the top set of leaves exposed. Once the trench is full, the plant will have enough space to set a full yield of tubers. Alternatively, you can hill on top of flat ground, but make sure that your hilling spreads in at least a 12 inch (30 cm) radius around the plant. 18 inches (45 cm) is even better, since seed grown potatoes can have very long stolons. I find that a 12 inch (30 cm) in row spacing is about right for modern potato seedlings and 15 inches (37.5 cm) works better for short day Andean types, as they typically grow very large by the end of the growing season. Increase the spacing by half for dry farming.

If you have made it this far, you might also want to take a look at the top 10 beginner mistakes with true potato seeds.

Maturity

Potato varieties have different maturation periods, ranging from about two to six months. Most commercial varieties fall into three groups: early (first early), maturing in 10-12 weeks; mid-season (second early), maturing in 14-16 weeks; or late (maincrop), maturing in 16-24 weeks. Early and mid-season varieties have a determinate plant form; they grow to a fixed size, flower, and then begin dying back. Late varieties have an indeterminate plant form; they grow and flower for an extended period, usually becoming large, bushy, or sprawling plants. In commercial fields, late varieties are often killed with herbicide to prevent the plants from growing for too long, but small growers will usually allow them to grow until natural senescence to obtain the greatest possible yield.

Maturity also affects production of true seed. Early varieties are very poor berry producers. The problem is that they begin forming tubers so quickly and rapidly that there is direct competition with flowering. If an early variety flowers at all, it is likely to drop the flowers and form no berries. If berries are formed, they often drop before maturing. It can be a real challenge to get true seed from an early variety. The best way to get an early variety to hold berries is to limit the amount of energy that it can put into tubers. For example, you can remove the tubers as they form or you can grow the plant in a very small pot. You can also graft the variety onto a non-tuberous Solanum like a tomato. It is usually easier to get berries from mid-season varieties, although their determinate forms mean that the number of berries per plant is often low. Late varieties are, by a wide margin, the easiest types to get berries from and they often have very high yields of berries as well.

First year seedlings grown from true potato seeds typically grow for a longer period than they will when propagated from tubers. This can result in a surprising number of differences. It is not unusual for a seedling to grow for a month longer than when it is later grown from tubers. If it is an early variety, it may flower and form berries easily in that first year but never again. The difference in maturity may result in larger tubers and a different intensity of color. For example, varieties with blue or red flesh may show it more strongly in the seedling year.

Harvest

For information about harvesting berries, see the Propagation section below.

As with potatoes grown from tubers, it is time to harvest after the tops die down. Once the tops die, the skins of the tubers toughen, which reduces the amount of damage that you do when digging them up. Think about how you want to evaluate them before you start harvesting. You might want to take note of things like the length of the stolons that can’t be evaluated later. Taking pictures of each plant as you harvest can be a useful record. If you want to measure yield, then you will need containers for each plant so that you can weigh them individually later.

Selection

At some point, you will need to evaluate the potatoes that you have harvested and decide which, if any, you will grow again. Some criteria are obvious: color, shape, and flavor are all fairly easy decisions. You might also want to think about maturity, dormancy, and disease resistance.

Color

If skin and flesh color are traits that are important to you, you will need to maintain separate populations by color for the best results. Potato color genetics involve a number of genes that interact to produce the different color combinations. Blue and white are likely to overwhelm other colors in a mixed population.

Maturity

Potatoes have varying maturities. Early and mid season potato plants grow to a certain size, set tubers, and then senesce uniformly. Late varieties will continue to grow for as long as conditions allow, branching and flowering over a long periods, producing very large plants and, in some cases, very large harvests of tubers. This is not a useful trait for big agriculture, since it makes it difficult to time the harvest. Large scale potato growers favor early and mid season types and so these are the types that are overwhelmingly sold as seed tubers. Where indeterminate varieties and big agriculture intersect, as is the case with the classic variety ‘Russet Burbank’, the solution usually involves killing the crop with herbicide in order to harvest while weather is still favorable. In the garden, you might prefer late varieties if you live in a climate with a long growing season, since harvest timing is not as great a concern.

Early varieties are important for both regions that have short growing seasons and regions where blight arrives in late summer. You can easily select early varieties in the seedling stage by allowing them to form tubers in the trays. The early varieties will senesce without ever being transplanted to the field and you can retain the microtubers for planting. Otherwise, they are equally easy to detect in the field as long as you start growing them early enough in the year. The first to senesce are your early varieties. Just make sure that they died back naturally and not as the result of disease!

Dormancy

You will want to track how many days your tubers last in storage before they begin to sprout. The dormancy period needs to be long enough that the potatoes survive until planting time.

It appears that tuber dormancy and TPS dormancy are linked (Simmonds 1964). Varieties that have little tuber dormancy will often also have little TPS dormancy and vice versa. This can be useful for high latitude potato breeders: seed lines can be sown soon after collection to evaluate for dormancy. Those that germinate quickly can be discarded under the assumption that their tubers will have poor dormancy.

Disease Resistance

The simplest approach to breeding for disease resistance is to eliminate plants that show any symptoms during the growing season. This can be very effective, but it isn’t necessarily the best place to start. A wider base of resistance genes can be formed by selecting plants in your first few breeding seasons that are vulnerable to disease, but resilient enough to survive and produce a yield. Although counterintuitive, this has the potential of producing more resistant plants in the long run (Robinson 2007). That is an extreme simplification. For more information, I recommend that you take a look at both the Amateur Potato Breeder’s Manual and Return to Resistance by Raoul Robinson.

Safety

At some point after harvest, you will be ready to give your new varieties a taste test. Some people have heard horror stories about potatoes developing toxic levels of the glycoalkaloids solanine and chaconine. Potatoes that are exposed to sunlight have increased levels of these compounds, which is why you don’t eat potatoes that have turned green. Some of the wild ancestors of the potato have much higher concentrations of these compounds even without exposure to sunlight and this trait can show up in potatoes grown from true potato seeds.

In one famous case, Lenape, a potato bred by the Wise Potato Chip Company turned out to have a level of solanine high enough to occasionally cause nausea and vomiting (Koerth-Baker 2013). Most people had no problems with it and the flavor was said to be really good. Interestingly, the bitter characteristics of the glycoalkaloids are a significant component of potato flavor, but if you go too far, the potatoes become unpleasantly bitter and unsafe to eat.

Safety is always a relative consideration. Some people eat potato tops, which are much higher in glycoalkaloids than the tubers. They appear to do so without ill effects (Phillips 1996), so there is probably considerably more tolerance for these compounds in the human diet than the estimated lethal dosage indicates. That isn’t a suggestion that you should try to find the upper limit, but will help to put the danger in context.

No domesticated potato that you grow from TPS is likely to do you serious or permanent harm when consumed in small amounts. Solanine is quite bitter, so as it rises in concentration, the odds that you will finish chewing a mouthful decline dramatically. Potatoes that taste just a little bitter may cause no reaction at all in some people, but unpleasant results in others. The typical response to a small overdose of solanine is diarrhea. A moderate overdose takes it up to nausea and vomiting. A serious overdose can result in confusion, weakness, and unconsciousness (Ruprich 2009). Symptoms may appear about four hours after consumption (Mensinga 2005).

The best practice for evaluating new varieties would seem to be starting with small amounts. I cook new varieties in the microwave and eat them plain, so that bitter flavors are not masked. I have now tasted thousands of potatoes grown from true seed, found only a few that were terribly bitter, and I have never gotten sick taste testing them. Potatoes that aren’t noticeably bitter are probably very safe, although some people are insensitive to bitter flavors. If you are one of them, you might need to get some help with your taste testing.

For more information about glycoalkaloids and safety, follow the link.

Propagation

Once you have managed to grow potato plants to sexual maturity, it is time to think about the next generation. It is time to pollinate some flowers, collect the berries, and extract the seeds from them.

Pollination

If you want to keep growing potatoes from TPS, you will need to produce more seeds. There are many ways to go about this. You can plant a group of varieties that you like and allow them to open pollinate. You can perform hand pollinations between varieties. With self compatible tetraploid varieties, you can also isolate varieties that you like and let them self pollinate.

The first thing that you will need is some potato flowers. In favorable weather conditions, flowers appear three to six weeks after emergence from tubers or two to three months after germination from seed. The most favorable conditions for flowering and berry production are daytime temperatures in the 60s F (15 to 20 C) and nighttime temperatures in the 50s F (10 to 15 C), accompanied by high humidity. Some varieties will flower in warmer, drier conditions, but very few will flower reliably when daytime temperatures rise above 85° F and berries tend to drop early in warm weather. The length of flowering is linked to the the maturity of the variety and may last as little as a week, for early varieties, to several months for late varieties. I would expect about two weeks on average with commercial varieties. Some pesticides are known to suppress flowering in potatoes, so you might want to avoid spraying plants that you plan to use for seed production.

Self-Compatibility and Male Sterility

Some potato varieties are self-compatible; they can pollinate themselves and produce seed. Other varieties are self-incompatible; they require a different variety to pollinate them. Additionally, many varieties are male sterile – their pollen cannot be used to produce seeds. Both of these reproductive barriers must be absent for successful self pollination.

Nearly all the potatoes that are commonly grown outside South America are tetraploid. Both reproductive barriers are important with tetraploids. Some tetraploid potatoes are both self compatible and have fertile pollen. These will often produce berries without any effort on your part, although they will likely produce more berries if you give them a hand. These varieties are reasonably common, but not the majority. More commonly, tetraploid potatoes are male sterile, meaning that their pollen cannot be used to pollinate either the variety itself or another variety. These varieties require pollination by a fertile variety in order to produce seed. Male sterility is inherited, so if you collect seed from a variety that is male sterile, you can generally expect that all of the progeny will be male sterile as well.

Diploid domesticated potatoes are rare outside of South America (so, you probably know if you are growing them). With rare and specific exceptions, these potatoes are all self incompatible; they require cross pollination with another variety in order to form seed. On the other hand, they are rarely male sterile, so almost any diploid potato variety can be used to pollinate any other. Generally speaking, if you don’t have two different diploid varieties flowering at the same time, you shouldn’t expect to see any berries.

Methods of Pollination

The simplest, but least effective, method of pollination is to let nature take its course. If you have a lot of bumblebees, they can do a useful amount of pollination. If you have some self compatible varieties that produce a lot of pollen, even wind blowing the plants may be enough to produce some berries. Even with a lot of bees, though, I usually find that the number of berries is much lower than it can be with a little help. This is particularly true where there are any additional obstacles. If you have a lot of self-incompatible, male sterile, poor or short flowering varieties, less than ideal conditions, or few pollinators, you can make a big difference.

One of the easiest things you can do is to walk around the garden and give a little shake to any plants that are flowering. This can be just enough to dislodge a little pollen and get those flowers to self pollinate. The next step up is to get an electric toothbrush and apply it to the base of flowers for a few seconds. The vibration simulates the buzz pollination that bumblebees perform and is very effective at self pollination. Neither of these techniques will help much when a variety is self-incompatible or male sterile.

If you have those tricky self-incompatible or male-sterile varieties (and you probably do), then the best way to help them along is to collect pollen from fertile varieties and use it to pollinate their flowers. The easiest way to do this requires three tools: an electric toothbrush, a small container (preferably dark, so that you can see the whitish pollen), and a small paint brush. Hopefully, you have been able to identify at least one variety that self-pollinates. That one will have fertile pollen, so all you need to do is position the small container under the anther cone and vibrate the base of the flower for a few seconds. Pollen will fall into the container. You might have to do this with ten to twenty flowers before you obtain enough pollen to easily see. Then, all that you need to do is dip the paint brush in the pollen and apply it to the stigma (the little green bulb that sticks out of the middle of the anther cone). Ideally, you want to apply enough pollen that you can see the stigma change color from green to white.

Pollination Strategies

When hand pollinating, you have the choice of performing open pollination or controlled pollination. Open pollination is the easier choice. You simply collect pollen from one set of flowers and transfer it to another. Because you have not blocked other pollinators from reaching the flower, it is possible that the pollination you perform won’t be the only one. The flower might have been pollinated before you get to it and it might be pollinated again after. This is the nature of open pollination. A potato berry can form several hundred seeds and each seed is the result of a separate pollination. It is rare that a single application of pollen will fully pollinate a potato berry. When hand pollinating potato flowers, repeating the pollination at least once produces significantly better seed set than a single pollination (Pallais 1985). My less scientific observation is that, the more times you pollinate a flower, the better. As long as a flower still has a stigma that has not deteriorated, I keep pollinating it daily. When a variety has poor female fertility, I pollinate it three times a day.

Unless I am doing controlled pollination, I usually mix the pollen of multiple varieties and use the mixture to pollinate flowers. This is known as bulk pollination. I might mix together the pollen of any variety that is flowering on a given day or I might mix together pollen of varieties that share a trait. For example, I often pollinate blue flesh varieties with bulk pollen collected only from other blue flesh varieties. Bulk pollination will generally produce the largest number of berries, since the fertility of potato pollen varies. Pollen collected from a wider population is bound to contain more highly fertile contributions.

If you want to be certain about which variety is the pollen parent, then you need controlled pollination. Controlled pollination requires emasculating the flower: removing the stamens before their pollen matures. This procedure is beyond the scope of this guide, but you can find instructions and even videos on the Internet, particularly for tomatoes, which are similar. In brief, you open the flower just before it would first open naturally and pluck out the stamens. This prevents self-pollination. You can then pollinate the flower and bag it to prevent access by other pollinators. Of course, if you are pollinating a male sterile variety, you don’t need to worry about emasculating it. In that case, you can get reasonably assured controlled pollination by pollinating flowers on the day that they first open and then bagging them. There are a lot of disadvantages to male sterility, but also some advantages.

You can store potato pollen that you have collected for later use, which may be important if the varieties that you wish to cross flower at different times. You can store pollen at room temperature for about a week, in the refrigerator for about a month, and in the freezer for about a year without major loss of viability. For storage, put pollen in an airtight container with a packet of silica desiccant to ensure that it maintains a low moisture level. Don’t freeze pollen until it has been exposed to the desiccant for at least 48 hours.

Collection

It takes a minimum of six weeks for berries to mature (Simmonds 1963). The optimum time for berries to mature varies from one variety to another and I would generally prefer to not harvest berries that are less than eight weeks old. In warmer climates, berries can mature more quickly. If you can wait until the berries drop from the plant naturally, that is the best approach, but pests may make that difficult. In that case, harvest the berries while they are still firm and allow them to ripen in a protected place. I often shake the plant gently and collect any berries that drop off, but this can be a bad idea with some varieties that hold their berries poorly. I typically store berries in quart size plastic containers until they are fully ripe and begin to break down. They are very easy to process at that point. A quart of potato berries weighs about a pound and produces an average of 4.8 grams of seed (roughly 10,000 seeds), but different varieties here have produced a range of almost zero seeds per quart to as much as 9 grams, which is nearly 20,000 seeds.

Berries should be protected from frost. Depending on how gradually the temperatures have declined and how ripe the berries are, they may have a high enough sugar content to avoid frost damage, but this is not reliable. A freeze will generally destroy any seeds in the berries if it lasts long enough to penetrate, so don’t store berries in an unheated shed where they might freeze. In an emergency, like an early frost, it is worth collecting any berry that is at least 1/2 inch in diameter. The seeds will be small and have low viability, but you will often get some to germinate.

Extraction

Once you have harvested mature berries, you need to extract the seeds. There are a number of ways to go about this. The first step is patience. Keep the berries in a sealed container to prevent them from drying out and then wait until they are nice and soft. If you can’t easily rupture a berry by squeezing it, they aren’t ready yet. It is better to wait too long than not long enough. At room temperature storage, you have roughly six to nine months to extract the seeds before germination begins to decline. I have occasionally left berries as long as a year before extracting them and germination is usually pretty bad by then.

Once the berries are soft, the seeds will more easily separate from the flesh. For small quantities of 50 berries or less, you can merely cut berries in half and squeeze out the seeds. I recommend squeezing the contents of the berries into a quart of water and then leaving them to ferment for a week. Then just rinse the seeds and dry them for storage. This simple procedure is all that most people will ever need, but if you are contemplating extracting seed from hundreds or thousands of berries, read on.

You can see the process that I use to extract TPS here: Potato: Extracting true potato seed (TPS)

For large extractions, a blender is the most common tool. I add a quart of berries to the pitcher along with a quart of water and blend for 30 seconds. You then run the mush through an appropriately sized sieve to pass the seeds, but not the debris. This works very well, but it can damage some of the seeds, particularly if the berries are not yet fully ripe. The International Potato Center has reported that a meat grinder provides a superior result, breaking up berries with very little damage to the seeds, and another study found that using a mixer with rubber beaters produced the highest percentage of germinable seed (Gallagher 1984). I have been using a blender for years and have never found it necessary to investigate the other options.

Once the basic extraction is done, you have two choices for how to clean the seed: fermentation or detergent.

Fermentation for 4 days at 86° F (30° C) produces clean seed (Pallais 1985). The only problem with fermentation is that you often don’t completely get rid of the mucilage and the seeds have a tendency to clump when drying. You can speed things up and get more vigorous fermentation by adding some dry yeast.

Detergent generally produces TPS with less mucilage, which clumps less during drying as a result. This may be an additional layer of protection against surface contamination. I use a 10% solution of the detergent trisodium phosphate (TSP) to clean potato seeds. I add them to the solution and stir them with a magnetic stirrer for 1 hour before rinsing them clean. TSP is a food-safe additive and has been widely studied as seed cleaner. It can be purchased at hardware stores in the United States and may still be available as a laundry detergent in other countries or not available at all, as phosphate detergents are considered an environmental hazard when used at a large scale. (The tiny amount you will use for cleaning seeds is insignificant – it used to be used in laundry detergent and such widespread use was adding a lot of excess phosphate to wash water.) A 10% solution can be made by adding 1 tablespoon of TSP to a cup of water.