Wild Potatoes (Solanum section Petota)

Overview

- There are roughly 100 species of wild potatoes; the exact number is always in flux as the taxonomy changes.

- There are two main concentrations of wild potato species: the Andes and the mountains of central Mexico.

- Wild potato tubers are typically very small, although the plants of some species are much larger than domesticated potatoes.

- Many wild potatoes have very long stolons, which can make them difficult to manage in the ground.

- Most wild potato species are not safe to eat, other than in small amounts, due to high glycoalkaloid content.

- Wild potatoes can be hybridized with domesticated potatoes to introduce new traits.

- Wild potatoes can be propagated from tubers or seeds, but seeds are more commonly available.

Introduction

This guide is a work in progress and it is likely to remain so for a long time. I edit live on the site, so please excuse parts that are broken, incomplete, or poorly written. I will fix them eventually. It takes a minimum of two years for me to grow and document species and, in most cases, I am only growing one or two accessions. I would eventually like to grow enough different accessions of each species to get a good representation of its diversity, but that could take decades at my pace. People often ask if this guide is available in print. If I get to the point where I have at least documented all the species available in the USA, I will try to compile it into a PDF or eBook, but demand for a non-scholarly work on wild potatoes is pretty low, so I think it is safe to say that there will never be a print version.

This is a guide to growing and using potato species other than the domesticated potato, Solanum tuberosum. There are several excellent monographs on wild potatoes that provide detailed taxonomic and botanical information and I will not attempt to reproduce those here. The goal for this guide is to provide information about cultivating, eating, and breeding with these species, and to provide photographs that do a reasonable job of covering the phenotypic diversity within the species.

Before we go any further, let’s make sure that you are in the right place. If you are looking for information about South American potatoes that have unusual colors and shapes (often called “primitive” potatoes), you are not looking for wild potatoes. You are looking for domesticated Andean potatoes. Wild potatoes are very interesting in their own way, but they are rarely colorful, are typically very small, and frequently bitter and dangerous to eat.

While wild potatoes are often used in potato breeding, little effort has been put into improving them individually relative to S. tuberosum. To my way of thinking, this is a great opportunity for small and hobby breeders. Anyone with interest could easily choose to adopt a wild potato species and become a specialist in its cultivation and breeding. By working on each species, it would be possible to produce improved varieties. By improving size and reducing glycoalkaloid content, for example, it might be possible to introduce new species to more widespread cultivation. Improved varieties might also be used more effectively to introduce traits through breeding with S. tuberosum. Many wild traits that have been incidentally introgressed into domesticated potatoes along with targeted wild genes have proved to be valuable and, in some cases, moreso than the originally targeted genes (Leue 1982). The greatest barrier to working with the wild species is simply figuring out where to begin and I hope that this guide will help in that regard.

Germplasm supplied by the USDA Potato Introduction Station was used in the production of these guides.

About Wild Potatoes

Description

There are approximately 100 species of wild potatoes. For the purposes of this guide, a wild potato is a member of the genus Solanum that forms tubers, which corresponds to the Solanum section Petota, with the exception of the Etuberosum group, which includes several close potato relatives that do not form tubers. The number of wild species has been significantly reduced as a result of genetic analysis. Hawkes (1990) listed 235 species, but by the time that Spooner (2014) was published, the number had been reduced to 98 true species. There is still disagreement about the species boundaries and they are not used consistently. When searching the scientific literature or genebanks, it is important to be aware of synonyms. The new taxonomy is overwhelmingly used for North American publications, but much less so in the rest of the world. New papers are still being published that use the expanded taxonomy, particularly in South America, where gene banks still supply species under the old names. With such a wide range, encompassing many nations and cultures, wild potatoes are known by many names. In the Quechua language of the central Andes, they are known most commonly as atoq papa (fox potato) or sacha papa (mountain potato) and distinguished from weedy or feral domesticated potatoes, known as araq papa (toward potatoes) or k’ipa papa (from potatoes), although there are also many regional variations and names that refer to individual species or groups of species. In Spanish, wild potatoes are widely known by names such as papa del zorro (fox potato), papa del monte (mountain potato), papa del indio (indian potato), papa de vieja (old potato), and papa cimarrona (wild potato).

110 species are currently listed in this guide, including 9 additional nothospecies (natural hybrids between wild species) and 3 domesticated varieties that are hybrids with wild potatoes (S. ajanhuiri, S. curtilobum, and S. juzepczukii). Most likely this information is already out of date or will be soon. 91 species have detailed pages; the rest are not currently available in the USA, so I have not grown them. Wild potato species only grow natively in the Americas, where they range from southern Utah in the north to about the middle of Chile in the south. There are two main concentrations of these species: the Andes, from Venezuela to Argentina, and the highlands of central Mexico.

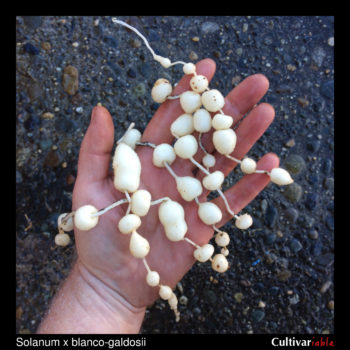

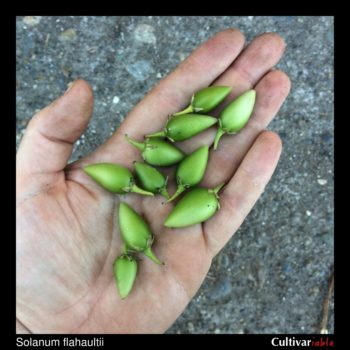

Wild potato species are not often cultivated and little is known about most of them, relative to the domesticated potatoes. They are really interesting plants and well worth growing even if you are not interested in eating or breeding them. Many have very attractive flowers and can make interesting ornamentals. Others have features that should surprise and delight even the most experienced potato grower. Wild species range from only a few inches to more than nine feet tall. While most produce small, round tubers, some form extremely unusual long, twisting, or chained tubers. One species is an epiphyte that grows in trees! Many have round berries, but some produce long, conical, or pointed berries that look more like chili peppers.

Edibility

Most sources describe the wild potato species as inedible, but that is not strictly true. Many are not considered safe to eat due to high glycoalkaloid content, but some species are just as edible as domesticated potatoes. Most species that have been tested have a fairly wide range of glycoalkaloid concentrations, so it is probably possible to select edible varieties even from species that often have unsafe levels. You can generally stay out of trouble by not eating potatoes that are bitter or sour, but some species may contain unknown toxic compounds that are not found in the domesticated potatoes. If you intend to experiment with eating wild species, proceed carefully. The individual species pages provide more detail about glycoalkaloid content and edibility, if available. I note in the guides when I have tasted tubers of a given species, but this is not a suggestion that you should taste them. Even if I have done it, it may not be safe.

To date, I have tasted the tubers of at least one accession of 62 species of wild potato. Of those, 19 species turned up at least one accession with tubers that tasted completely non-bitter to me. Another 28 turned up at least one accession that I would describe as only mildly bitter. The remaining 15 were strongly bitter. Even among species where I found non-bitter or minimally bitter plants, there are usually others that have much greater bitterness. The way that I experience bitterness also varies. Some species taste more sour than bitter and I have noticed that these are usually plants in which the primary glycoalkaloid is tomatine. Sometimes the bitterness is apparent immediately but, other times, it develops slowly. The speed of onset doesn’t seem to have much relationship with the ultimate intensity of the sensation. There are tubers that taste fine initially, even through several seconds of chewing, but then go on to produce a mouth-puckering bitterness or even burning sensation. Others hit you immediately with strong bitterness that then seems to abate. The flavor of strongly bitter tubers sticks with you. When I get a really bitter one, I can often still taste it an hour later.

Some wild potatoes tend to turn purple with exposure to sunlight, rather than green, but this is the same warning sign. This purple coloration also appears to develop at full maturity or as a stress response and often seems to be an indicator of bitterness, even in freshly dug tubers. That doesn’t mean that wild potato tubers that aren’t green or purple are safe to eat. You should always assume that wild potato tubers are high in glycoalkaloids.

Other Uses

Many wild potato species are quite ornamental, flowering heavily and for a long period of time. Species that I think are particularly worthy of attention for ornamental use include S. candolleanum, S. colombianum, S. infundibuliforme, S. paucissectum, S. raphanifolium, and S. violaceimarmoratum.

Invasiveness

Wild potatoes have small tubers and long stolons, a combination that leads to unwanted spread. There is great potential for some species to become invasive weeds in favorable climates. I have measured stolons from some species as long as eight feet, which amounts to an area of about 200 square feet. Imagine trying to dig an area that large to search out tubers the size of jelly beans! I recommend growing wild potatoes in pots to keep them contained. The good news is that you don’t really have to worry about plants spreading by seed, since the berries are relatively large and easy to collect.

Classification

The taxonomic classification of wild potatoes has changed considerably over time. Prior to this century, most classification was done based on morphology and we now know that morphology can be misleading. Genetic taxonomy has now largely replaced morphological classification.

As with domesticated potatoes, there is ongoing debate about the divisions between species. In North America, we mostly use the more recent taxonomy of Spooner (2014), which reduced to the count to about 100 species. In South America, it is still more common to use an updated version of Hawkes’s (1990) taxonomy, with more than 200 species. Obviously, this situation isn’t ideal and it adds some complexity when reading the literature. It isn’t unusual to have to map out two or three levels in changes in species when reading papers published in the past 50 years.

Pronunciation

With some reluctance, I give guidance about the pronunciation of scientific names in the species profiles. There is no completely standard pronunciation for scientific names and they are often pronounced quite differently by people of different nationalities and even by people of the same nationality. Latin and ancient Greek are dead languages with no exact pronunciation. In many cases, the most common ways that we pronounce scientific names are in conflict with what we can deduce about the original pronunciation of those languages. This only becomes more complicated when scientific names refer to the names of contemporary people or places, which are not meant to be pronounced using the rules of Latin or Greek. If you recognize and know how to pronounce a person’s name within a scientific name, then you might prefer to pronounce it as would be correct for the person’s name. No one could fault you for this. But, if you don’t know how to pronounce the name or have a strong preference for consistency, you might just pronounce it as you would any other sound in our Latin/Greek amalgamation. In some cases, I give both alternatives.

All of these species belong to the genus Solanum, which is most commonly pronounced so-LAY-num. Many people also pronounce it so-LAH-num, including me. I have also heard SO-luh-num. I first heard it pronounced so-LAH-num and attempts to change my pronunciation have been inconsistent at best. This does not prevent anyone from understanding me. However you pronounce a name, do it confidently and most people will probably be too uncertain to attempt to correct you. I certainly won’t.

Series

Wild potatoes were originally grouped into several series based on morphology. While the series have been shown to correspond poorly to the genetic relationships between species in many cases, you will still need to be aware of them when reading most sources of information about wild potatoes.

Genome

Although wild potatoes share the vast majority of genes across all species, in some cases, there are enough shared changes that the genomes have diverged to the point where they no longer easily combine. There have been several different systems proposed, but the most recent and simplest describes three genomes: the A genome of domesticated potatoes and wild potatoes that were primarily included in the series Tuberosa, the B genome of North American diploid potatoes, and the P genome of some South American diploid species (P is for series Piurana, although modern genetic work has shown that potatoes in that series belong to more than one group.)

Clade

Probably the most current and best way of classifying potatoes is by clade. Spooner divided potatoes into three primary clades: a consolidated clade 1+2 of primarily 1EBN North American species, clade 3 of South American species that are not close relatives of the domesticated potato, and clade 4 of primarily South American species that are closely related to the domesticated potato.

Cultivation

Wild potatoes are adapted to specific climates and many fail to grow true to form when grown in a different climate. This is particularly true when plants are grown in greenhouses. Wild potatoes tend to grow unusually tall in greenhouses, which can result in a very different plant than you might expect. Plants from warmer regions tend to grow slowly when grown in cool climates and cool climate plants often fail to flower or set berries when grown in warmer climates. In most cases, the plants will prefer a slightly acidic to neutral soil. Most are happy in peat based potting mixes, but if your native soil is not alkaline, it should be fine as well. Most wild potatoes are native to higher elevations, where sunlight is strong, but they are also often under-story plants, where they grow in filtered sunlight, so they are fairly adaptable in this regard. The best yields will generally be achieved in full sun, unless your climate is significantly hotter than the native climate for the species that you are growing.

Most wild potatoes have very long stolons, ranging between two and four feet. It can be very hard to harvest and manage plants that distribute tubers so widely. For this reason, wild potatoes are probably most often grown in pots. If you find pots difficult to manage, as I do, an alternative is to grow the plants in the ground in buried fabric pots. Gallon size fabric pots work very well for wild potatoes and I find that the plants are much happier growing in the ground. Stolons will occasionally try to escape over the lip of the pot, so some vigilance is required to prevent unwanted volunteers.

Propagule Care

Seeds

Wild potato seeds can be treated just as domesticated potato seeds. They should retain reasonably good germination at room temperature for three years. If you intend to store them beyond that, they will keep better in a refrigerator or freezer.

Tubers

Most wild potato species have good dormancy and will keep similarly to domesticated potatoes. Store them in a cool, dark place and they will usually keep for at least three months. Many species have longer dormancy than the domesticated potato.

Some species, like S. limbaniense, have minimal dormancy and need to be treated similarly to low dormancy domesticated diploid potatoes. The best practice with these is either to store them very cold, as close to freezing as possible, or store them in a single layer in a well-lighted environment, which will allow them to sprout, but will keep the sprouts short and manageable until you are ready to plant.

Climate Tolerance

Wild potatoes occur over a 5000 mile range, from Utah in the north to Argentina in the south. Many species grow at very high elevations, while others are found all the way down to sea level. With this kind of variation, it is hard to generalize about climate requirements. Most species do best where summer temperatures aren’t very hot and where moderate soil moisture is present through the growing season. In addition, most species will yield best in climate with mild fall weather because tubers often develop late in the year. For more information, see the individual species profiles below.

Photoperiod

Most wild potatoes are short day tuberizers, like Andean domesticated potatoes. In the northern hemisphere, they don’t begin to form tubers until after the autumn equinox. This mostly limits their cultivation outdoors to fairly mild climates that don’t experience frost until November, although some species have good frost tolerance and can probably survive to form tubers in more challenging climates. Some species are day neutral and can form tubers at any time of year. Solanum acroscopicum, S. cardiophyllum, S, jamesii, and S. microdontum are examples of day neutral tuberizers. There are probably others, particularly among species that occur in the northern and southern extents, like northern Mexico and Argentina.

Planting

Seeds

In most cases, the ideal germination conditions for wild potato seeds are unknown or at least unpublished. I typically use the same conditions to start wild potato seeds as I do domesticated potato seeds: a daytime temperature of 65 degrees F and a nighttime temperature of 55 degrees F. These conditions work for many wild species, but that doesn’t mean that they are the best conditions. The germination of some species is inhibited by alternating temperatures (Bamberg 2018), while other species may benefit from inverse alternation, with warmer temperatures at night and cooler during the day. The USDA Potato Introduction Station recommends a constant temperature of 68 degrees F for germination (Bamberg 2017b). Some species have prolonged, slow germination, a phenomenon known as “trickle germination.”

Dormancy is often stronger in wild potato seeds than domesticated seeds. If you intend to sow seeds in the first year after harvest, treatment with gibberellic acid is usually necessary to achieve a reasonable germination rate. Not every species is the same in this regard and there are some that are inhibited by GA3. See the growing guides for the species that you are working with for more information.

Tubers

Wild potato tubers can generally be planted 2-3 inches deep and otherwise left alone. The tubers are usually small enough that you won’t benefit from hilling them. If you find that you are getting lots of satellite plants, the stolons are running just under the surface and you might want to add a little more soil. If you chit the tubers before planting, you will get a more uniform stand. This is particularly true with species that have strong and irregular dormancy, which is the case for many of the North American species.

Propagation

Vegetative Propagation

Wild potatoes are more often propagated by seed than by tubers because there are few improved selections. Tubers must be grown every year, while seeds will store for longer periods. That said, while you are actively working with a particular species, it is easy enough to keep them going by replanting tubers, just as with domesticated potatoes. The good news is that most wild potatoes are easy to grow from tubers. They generally have good dormancy, some of them much better than domesticated potatoes. The bad news is that many of the wild species are short day tuberizers, so it will be difficult to save tubers for plants grown outdoors in cold climates.

Some species are sexually dysfunctional and can only be maintained clonally. For example, most triploids will not set seed and a small number of hybrid and diploid species like Solanum ajanhuiri are effectively sterile.

Sexual Propagation

Although there are some exceptions, most wild potatoes flower abundantly and will produce good seed crops. Typically, they are more reliable at forming berries than domesticated potatoes.

It has often been reported that self-compatible species require pollination in order to set berries. Most potato research is done in greenhouses, so the most likely reason for this is a lack of insect pollinators, particularly bumble bees, which buzz pollinate potato flowers. In the absence of pollinators, self compatible flowers can simply be buzzed with an electric toothbrush to dislodge pollen and ensure self-pollination. In my experience, plants of self-compatible species fruit heavily when grown outdoors.

Bamberg (2017) studied the effect of fertilization on seed production and quality in 31 species of wild potatoes and found that supplemental fertilization substantially increased seed production but that the quality of the seed was not changed. So, if you need to produce large amounts of seed, fertilizing around flowering time may be helpful.

Self-Compatible Polyploids

Most of the even polyploid species are self compatible. Some, such as S. acaule, S. demissum, and S. guerreroense, are typically such efficient self-pollinators that they will not easily cross with other varieties or species without emasculation and hand pollination. They usually set a large crop of berries with no intervention. Because they are such good self-pollinators, they tend to be inbred and substantially homozygous. If you are starting from a diverse seed source and want to maintain some of that diversity, you should save seed from as many varieties as possible. You can also maintain diversity by making crosses between different accessions. This usually requires opening and emasculating the flower to prevent self-pollination.

Self-Compatible Diploids

There are only three diploid species with any known degree of self-compatibility: S. polyadenium, S. verrucosum and certain lines of S. chacoense. If you want to maintain the level of diversity in the starting population, it is best to cross as widely as possible within that population and mix the resulting seed.

Self-Incompatible Diploids

The majority of diploid wild potatoes are self-incompatible. When working with these species, you will need at least two plants that flower simultaneously in order to save seed. The good news is that you won’t have to work hard to maintain diversity with these species.

Odd Polyploids

Triploid and pentaploid species are sexually dysfunctional. Pentaploids will usually set seed, but triploids rarely will. In either case, seeds will not produce plants with the same level of ploidy as the parent, so seed is not a good way to propagate these species. Seed may still be useful for breeding.

Crop Development

Breeding with wild potato species is usually focused on moving wild genetics into the domesticated potato (S. tuberosum). It doesn’t necessarily have to be that way though. There are three major clades of wild potatoes: clade 4 (A genome) includes the domesticated potato and many 2EBN species that are directly compatible with it at the diploid level, clade 3 (P genome) includes primarily diploid 2EBN Andean species, and clade 1+2 (B genome) includes primarily diploid 1EBN North American species. Although there are many tricks for moving genes between these clades, it isn’t easy. A different way to look at the situation might be to primarily do breeding in-clade. Clade 4 species can be used in breeding with the domesticated potato. For clade 1, S. cardiophyllum and S. ehrenbergii might be a suitable nucleus for breeding. For clade 3, S. acroscopicum could be a suitable nucleus. These suggested nucleus species have traits that make them more suitable for domestication than other members of their respective clades. I’m sure that I am far from the first person to suggest such a strategy, but it may hold more appeal for small breeders who value novelty even at the expense of more marketable traits.

Species that have been used in improved cultivars of Solanum tuberosum include at least S. acaule, S. bulbocastanum, S. candolleanum, S. commersonii, S. demissum, S. maglia, S. microdontum, S. stoloniferum, and S. vernei.

Wild Potato Species Profiles

Gallery

This filterable gallery is followed by several tables that present much of the same information in a fixed format.

[pt_view id=”82a38a5tav”]Table of Species

Species that do not link to a profile are currently unavailable in the USA, or at least I have been unable to obtain them. I will add them in the future if I am able to find them. This table is sortable by column. Continent shows whether the variety is from North or South America. Series shows the morphological group assigned by Hawkes (1990). This is historical information only, as more recent genetic analyses have shown little support for prior morphological groupings. Clade shows the modern evolutionary groupings, primarily from Spooner (2014). Ploidy shows the possible levels for the species, listed in order of frequency. EBN shows the endosperm balance number for the minimum level of ploidy associated with the species (so, for example, if a species lists ploidies of 2x and 4x and an EBN of 2, that EBN is associated with the diploid (2x) level of ploidy.

| Species | Continent | Series (Hawkes) |

Clade (Spooner) | Ploidy | EBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solanum acaule | SA | Acaulia | Mixed | 4x, 6x |

2 |

| Solanum acroglossum | SA |

Piurana | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum acroscopicum | SA | Tuberosa | 3 |

2x, 4x |

? |

| Solanum x aemulans | SA | Acaulia | 4 | 3x, 4x | 2 |

| Solanum agrimoniifolium | NA |

Conicibaccata | 3+4 | 4x | 2 |

| Solanum ajanhuiri | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum albicans | SA | Acaulia | 3+4 | 6x | 4 |

| Solanum albornozii | SA | Piurana | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum anamatophilum | SA | Cuneoalata | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum andreanum | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x, 4x | 2, 4 |

| Solanum augustii | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum ayacuchense | SA | Conicibaccata | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum berthaultii | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x, 3x | 2 |

| Solanum x blanco-galdosii | SA | Piurana | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum boliviense | SA | Megistacroloba | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum bombycinum | SA | Conicibaccata | 3+4 | 4x | ? |

| Solanum brevicaule | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x, 4x, 6x | 2, 4 |

| Solanum x brucheri | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 3x | ? |

| Solanum buesii | SA | Conicibaccata | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum bulbocastanum | NA | Bulbocastana | 1 | 2x, 3x | 1 |

| Solanum burkartii | SA | Conicibaccata | 4 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum cajamarquense | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum candolleanum | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x, 3x | 2 |

| Solanum cantense | SA | Piurana | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum cardiophyllum | NA | Pinnatisecta | 1 | 2x, 3x | 1 |

| Solanum chacoense | SA | Yungasense | 4 | 2x, 3x | 2 |

| Solanum chilliasense | SA | Piurana | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum chiquidenum | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum chomatophilum | SA | Conicibaccata | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum clarum | NA | Bulbocastana | 1 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum colombianum | SA | Conicibaccata | 3+4 | 4x | 2 |

| Solanum commersonii | SA | Commersoniana | ? | 2x, 3x | 1 |

| Solanum contumazaense | SA | Conicibaccata | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum curtilobum | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 5x | 4 |

| Solanum demissum | NA | Demissa | Mixed | 6x | 4 |

| Solanum x doddsii | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum dolichocremastrum | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum x edinense | NA | Demissa | 4 | 5x | ? |

| Solanum ehrenbergii | NA | Pinnatisecta | 1 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum flahaultii | SA | Conicibaccata | 3+4 | 4x | ? |

| Solanum gandarillasii | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum garcia-barrigae | SA | Conicibaccata | 3+4 | 4x | ? |

| Solanum gracilifrons | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum guerreroense | NA | Demissa | Mixed | 6x | 4 |

| Solanum hastiforme | SA | Megistacroloba | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum hintonii | NA | Pinnatisecta | 1 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum hjertingii | NA | Longipedicellata | 1+4 | 4x | 2 |

| Solanum hougasii | NA | Demissa | Mixed | 6x | 4 |

| Solanum huancabambense | SA | Yungasense | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum humectophilum | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum hypacrarthrum | SA | Piurana | 3 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum immite | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x, 3x | 1 |

| Solanum incasicum | SA | Tuberosa | ? | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum infundibuliforme | SA | Cuneoalata | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum iopetalum | NA | Demissa | 3+4 | 6x | 4 |

| Solanum jamesii | NA | Pinnatisecta | 1 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum juzepczukii | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 3x | 2 |

| Solanum kurtzianum | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum laxissimum | SA | Conicibaccata | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum lesteri | NA | Polyadenia | 1 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum lignicaule | SA | Lignicaulia | 4 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum limbaniense | SA | Conicibaccata | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum lobbianum | SA | Tuberosa | 3+4 | 4x | 2 |

| Solanum longiconicum | NA | Conicibaccata | 3+4 | 4x | ? |

| Solanum maglia | SA | Maglia | ? | 2x, 3x | 2 |

| Solanum malmeanum | SA | Commersoniana | ? | 2x, 3x | 1 |

| Solanum medians | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x, 3x | 2 |

| Solanum x michoacanum | NA | Pinnatisecta | 1 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum microdontum | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x, 3x | 2 |

| Solanum minutifoliolum | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum mochiquense | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum morelliforme | NA, SA |

Morelliformia | 1 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum multiinterruptum | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x, 3x | 2 |

| Solanum neocardenasii | SA | Tuberosa | Neocardenasii (2018) | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum neorossi | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum neovavilovii | SA | Conicibaccata | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum x neoweberbaueri | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 3x | ? |

| Solanum nubicola | SA | Conicibaccata | 4 | 4x | 2 |

| Solanum okadae | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum olmosense | SA | Olmosiana | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum oxycarpum | NA | Conicibaccata | 3+4 | 4x | 2 |

| Solanum paucissectum | SA | Piurana | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum pillahuatense | SA | Conicibaccata | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum pinnatisectum | NA | Pinnatisecta | 1 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum piurae | SA | Piurana | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum polyadenium | NA | Polyadenia | 1 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum raphanifolium | SA | Megistacroloba | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum raquialatum | SA | Ingifolia | 3 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum x rechei | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x, 3x | ? |

| Solanum rhomboideilanceolatum | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum salasianum | SA | Conicibaccata | 4 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum x sambucinum | NA | Pinnatisecta | 1 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum scabrifolium | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum schenkii | NA | Demissa | Mixed | 6x | 4 |

| Solanum simplicissimum | SA | Simplicissima (Ochoa) |

3 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum sogarandinum | SA | Megistacroloba | 4 | 2x, 3x | 2 |

| Solanum stenophyllidium | NA | Pinnatisecta | 1 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum stipuloideum | SA | Circaefolia | Neocardenasii (2018) | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum stoloniferum | NA | Longipedicellata | Mixed | 4x | 2 |

| Solanum tarnii | NA | Pinnatisecta | 1 | 2x | ? |

| Solanum trifidum | NA | Pinnatisecta | 1 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum trinitense | NA | Conicibaccata | 3 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum x vallis-mexici | NA | Longipedicellata | ? | 3x | ? |

| Solanum venturii | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum vernei | SA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum verrucosum | NA | Tuberosa | 4 | 2x, 3x, 4x | 2 |

| Solanum violaceimarmoratum | SA | Conicibaccata | 4 | 2x | 2 |

| Solanum wittmackii | SA | Tuberosa | 3 | 2x | 1 |

| Solanum woodsonii | NA | Conicibaccata | 4 | 4x | 2 |

Wild Potato Species by Country

* Distribution in this country is uncertain

Notes

Maps

The distribution maps used in these guides are pretty gross approximations. They are suitable for understanding roughly where the species occurs in a given country, but you wouldn’t want to use them for any serious work. Maps are based on Google maps, for which Google retains the copyright.

Measurements

Several people have asked (some more politely than others) why I use Imperial measurements in this guide. I am based in the United States and, for better or worse, those are the measurements that we most commonly use. It is easy enough to convert back and forth. Since these guides are written in English and not specifically targeted at a scientific crowd, I have chosen to use the measurements that will probably result in the majority of readers doing the least work. I will add metric measurements at some point, as I have done for most of the guides on this site.

Potato Monographs

For more detailed taxonomic treatments, you should refer to the major monographs on wild potato species:

Index of Synonyms

[pt_view id=”fba1bb3pgw”]6 thoughts on “Wild Potatoes (Solanum section Petota)”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

A very useful guide to wild species, although it is a mystery why people would play with wild potatoes if not aiming to eventually cross them with cultivated species. There is that one may be feral potato growing wild in Maize fields from Venezuela to Bolivia closely related to S. Andigena (called Araq in some places) which is not mentioned. It is edible and harvested but not planted as it comes up like a weed on its own.

Thanks for stopping by! People grow plants for many reasons other than food and wild potatoes can be quite interesting. However, some wild potatoes seem to have potential for breeding into food crops on their own and there may be advantages to doing that. Many wild species have native names that are some variation on “araq,” but I don’t know if that translates into a particular species or hybrid in any part of the Andes.

Hey bill , I’m looking to buy some Solanum morelliforme do you have any left for sale?

Sorry, not this year. Probably in 2021.

I have grown Solanum etuberosum from seeds in Ukraine. About 50° north latitude and about 25° east longitude.

This species does not form tubers or they are underdeveloped.

I learned that this species grows in Chile, highlands, near the upper border of the forest.

USDA Hardiness Zone 7, even 6b. The plant tolerates low temperatures (-15° C even -20° C), it can be covered by snow for months (1 – 8 months).

I had no experience growing wild potatoes and didn’t get my seeds.

I grew wild potatoes for two years and then lost them.

I wanted to cross it with garden potatoes that sometimes overwinter in the ground.

Volodymyr

Hi Volodymyr. S. etuberosum is, unfortunately, not possible to cross with any wild or domesticated potato, at least as far as researchers have been able to discover so far. There have been many attempts to do so because S. etuberosum has unique blight and virus resistances that would be valuable in potatoes, but it appears that the genetic distance is just too great. All of the potatoes belong to Solanum section Petota and are at least theoretically capable of interbreeding. S. etuberosum belongs to section Etuberosum along with S. fernandezianum and S. palustre, none of which will cross successfully with members of section Petota.