Solanum ajanhuiri

| Common Names | Papa ayanhuri, Ajahuiri, Ajawiri, Kakahuiri, Yari |

| Code | ajn |

| Synonyms | Solanum x ajanhuiri |

| Clade | 4 |

| Series | Tuberosa |

| Ploidy | Diploid (2x) |

| EBN | 2 |

| Tuberization Photoperiod | Mixed |

| Self-compatibility | No |

| Nuclear Genome | A |

| Cytoplasmic Genome | P |

| Citation | Bukasov: Trudy Vsesoyuzn. S”ezda Gen. Selekts. Semenov. Plemen. Zhivotnov.3: 603. 1929. |

Description

Solanum ajanhuiri is perhaps better included among the cultivated species than the wild, but as a wild species hybrid, the dividing line isn’t entirely clear. This species is treated more like a wild species in breeding programs.

The specific epithet, ajanhuiri, is a Latinization of the native Aymara name. While there is no completely standardized pronunciation for scientific names, the most common way to pronounce this species is probably so-LAY-num ah-han-WEER-ee. Huaman (1980) notes that this transliteration from Aymara is not accurate and that “ajawiri” is the better rendering, since there is no n sound in the Aymara pronunciation. If disregarding the original pronunciation of names or native words, you might instead use the pronunciation ah-jan-WEER-ee.

This species is cultivated primarily in the Bolivian and, less so, the Peruvian altiplano, at elevations above 12,800 feet (3900 m), where it is valuable for its early bearing and frost resistance. Plants grow about 14 to 18 inches (35 to 45 cm) tall, although some take a more wild-type rosette form. Plants can have very different forms, particularly when grown under different conditions. Plants that take on a more rosette type form outdoors can grow very tall under greenhouse conditions. Most varieties have blue skin and some have blue flesh, less commonly white skin and yellow flesh, but only white varieties are currently available in the USA. (There is a blue variety available in the USA called Sisu Azul/ECOS Purple that was thought to be S. ajanhuiri, but genotyping showed that it is identical to the S. tuberosum group Chilotanum cultivar that goes by the common names ‘Purple Peruvian,’ ‘Vitelotte,’ and ‘Elmer’s Blue,” among others.) The flowers are blue or less commonly white. Berries are round, small, less than an inch, uncommon, but still present on most plants when other domesticated diploid potatoes are in flower. Berries tend to have lower seed counts than other domesticated potatoes, but the count improves if flowers are pollinated with bulk pollen from domesticated diploids.

The origin of S. ajanhuiri is believed to be as a hybrid between diploid S. tuberosum group andigenum (S. stenotomum) and S. boliviense. This is a contrast to the other frost resistant highland species, S. juzepczukii and S. curtilobum, which arose from crosses and backcrosses between S. tuberosum group andigenum and S. acaule. Some varieties of S. ajanhuiri may have been produced by backcrosses with either of the parent species. Huaman (1975) hypothesizes that cultivars in the Yari group are closer to S. boliviense, while cultivars in the Ajawiri group are closer to diploid domesticated potatoes. An additional group, Sisu, may be made up of crosses between S. acaule and S. ajanhuiri (Johns 1987). In addition to the cultivars, wild, weedy forms of this species are common and domesticated varieties were probably selected from these populations. Together, the various groups of S. ajanhuiri comprise a hybrid swarm.

Most varieties have high dry matter content (floury texture). Unlike the other frost resistant hybrid species, S. juzepczukii and S. curtilobum, S. ajanhuiri does not have high glycoalkaloids and can generally be eaten without processing (Ochoa 1990). All varieties have strong tuber dormancy.

There is an Aymara folk song about this potato that touches on its frost and wind resistance, among other attributes.

Resistances

S. ajanhuiri appears to have frost resistance that is nearly the equal of S. acaule, down to at least 23 degrees F and perhaps as low as 21. PI 599280 survived several frosts here that killed most domesticated potatoes with no damage at all. Because S. ajanhuiri includes everything from first generation crosses with S. boliviense to varieties that have incorporated multiple backcrosses to diploid S. tuberosum, frost resistance is likely to vary substantially between varieties.

| Condition | Type | Level of Resistance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frost | Abiotic | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Drought | Abiotic | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Globodera rostochiensis (Potato Cyst/Golden Nematode) |

Invertebrate | Somewhat resistant | Huaman 1980 |

| Phytophthora infestans (Late Blight) | Fungus | Not resistant | Bachmann-Pfabe 2019 |

| Potato Virus A (PVA) | Virus | Resistant | Barandalla 2010 |

| Potato Virus M (PVM) | Virus | Somewhat resistant | Barandalla 2010 |

| Potato Virus S (PVS) | Virus | Resistant | Barandalla 2010 |

| Potato Virus X (PVX) | Virus | Somewhat resistant | Ochoa 1990 |

| Synchytrium endobioticum (Wart) | Fungus | Immune | Hawkes 1945 |

Glykoalkaloid content

Osman (1978) found a TGA level of 7.1 mg /100 g for a single accession of this species. Because the putative parent species S. boliviense is high in glycoalkaloids, it is probably not safe to assume that all varieties have levels this low, but S. ajanhuiri is generally considered safe to eat without processing.

Johns (1986b) tested wild, weedy collections of S. ajanhuiri and found a range of 4 to 12 mg / 100 g. In different accessions, the primary glycoalkaloids were either solamarine or commersonine and tomatine. They also tested two domesticated clones and found levels of 10.5 and 13 mg / 100 g. The domesticated clones had primary glycoalkaloid compositions of either solamarine or solanine and chaconine. So, it seems that the glycoalkaloid composition of S. ajanhuiri is rather unpredictable.

Both of the accessions available in the USA are non-bitter and presumably low in glycoalkaloids.

Images

Cultivation

I have found cultivation of this species to be essentially the same as for other domesticated Andean potatoes (S. tuberosum group andigenum). This species is reported to be a short day tuberizer, but my experience so far does not agree with that. The cultivar ‘Jancko Ajawiri’ forms tubers in the summer. Tubers are produced in about 90 days when planted in late summer, but closer to 150 days when planted in spring. At 150 days, tubers can be five to six inches in length, but they tend to sprout and become tangled.

This species is propagated almost exclusively from tubers. It is possible to get true seed, but S. ajanhuiri is self-incompatible and the most effective pollinators are domesticated diploids, which will result in a reduced genetic contribution from S. boliviense in the progeny.

All varieties are noted to be significantly male sterile, but some may produce a little fertile pollen, as seed has been obtained from crosses between different varieties of S. ajanhuiri (Huaman 1982) and pollen stainability, which usually indicates fertility, was 23% in Ajawiri cultivars and 9% in Yari cultivars (Huaman 1980). Regardless of the percentage of viable pollen though, the amount of pollen produced by varieties available in the USA is very small and is is much easier to use them as the female in crosses with domesticated diploids.

Accessions Evaluated

The following accessions were examined to prepare this profile. I have evaluated 3/4 accessions currently available from the US Potato Genebank. Two of those accessions are misidentified and are not S. ajanhuiri.

PI 255490

A tetraploid true seed accession that is clearly not S. ajanhuiri.

PI 599279 “Laram Ajawiri”

A misidentified accession, confirmed with the genebank. Not S. ajanhuiri.

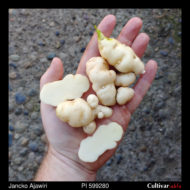

PI 599280 “Jancko Ajawiri”

A Bolivian accession. The tubers of this variety are small with deep eyes and look more like a wild potato. Excellent frost resistance. Sets berries fairly readily when pollinated with diverse domesticated diploid pollen. Tuberization appears to favor short days, although it will eventually set small tubers in longer days after four months. The Aymara word “jancko” means white and it was originally rendered in English works as “hanqho,” (La Barre 1947) so the j now used more commonly is the Spanish j, pronounced like an h in English.

PI 611096 “Yari Blanco”

To be evaluated in 2021.

Breeding

I have found that S. ajanhuiri actually sets seed pretty easily when pollinated by domesticated diploids and particularly with bulk diploid pollen. This makes sense, considering that there is evidence that some cultivars of this species represent backcrosses with domesticated diploids.

Crosses with S. tuberosum

| Female | Male | Berry Set |

Seed Set | Germ | Ploidy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. ajanhuiri | S. tuberosum 2x | High | Low | Yes | 2x |

Crosses with other species

| Female | Male | Berry Set |

Seed Set | Germ | Ploidy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. ajanhuiri | S. acaule | High | Low | Yes | 3x |