Solanum cardiophyllum

| Common Names | Cimatli, heartleaf horsenettle, heartleaf nightshade |

| Code | cph |

| Synonyms | S. lanciforme, S. coyoacanum |

| Clade | 2 |

| Series | Pinnatisecta |

| Ploidy | Diploid (2x), Triploid (3x), Tetraploid (4x) |

| EBN | 1 |

| Tuberization Photoperiod | Long Day |

| Self-compatibility | No |

| Nuclear Genome | B |

| Cytoplasmic Genome | W |

| Citation | Lindley: J. Hort. Soc. London 3: 70, fig. pg. 71. 1848. |

Description

Solanum cardiophyllum is a North American species, found primarily in Mexico. It is also present in some parts of the SW United States, but was probably introduced. It is commonly known as cimatli (along with S. ehrenbergii), heartleaf horsenettle, or heartleaf nightshade. This is one of the few wild potato species that was commonly used as food. The Aztec and the Chichimeca ate S. cardiophyllum and the practice continues in some parts of Mexico today (Johns 1990). In fact, there was at least one farm that was growing S. cardiophyllum, S. ehrenbergii, and S. stoloniferum for market in Jalisco as recently as 2010 (Villa Vazquez 2010).

The specific epithet, cardiophyllum, means “heart leaf,” which may refer to the early leaf shape of seedlings. It is formed from the Greek words “kardia,” for “heart,” and “phyllon,” for “leaf.” While there is no completely standardized pronunciation for scientific names, the most common way to pronounce this species is probably so-LAY-num kar-dee-oh-FILE-lum.

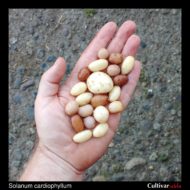

Plants can reach a little over two feet in height, although many are much smaller in the wild. Despite the name, the plant doesn’t really have heart shaped leaves, although the seedlings sometimes do. Although S. cardiophyllum has small tubers, reaching about an inch in diameter, they compensate with a rare trait in wild potatoes: palatability. In fact, the flavor is not easily distinguishable from domesticated potatoes. The level of glycoalkaloids in some accessions of this species is sometimes very low, about 2 mg/100 g (Johns 1990). That level is lower even than most domesticated varieties, although other accessions have been found to have much high and unsafe levels of glycoalkaloids (see below). Given the good edible qualities of at least some accessions, it is something of a mystery why the native Mexicans who domesticated so many other species did not improve S. cardiophyllum. Of course, it is possible that they did and we just don’t know about it. Current research is underway to determine if S. cardiophyllum might have been used by the Anasazi to improve the tuber size of S. jamesii (J. Bamberg, personal communication, 2018).

Although crossing wild potatoes to S. tuberosum is usually the goal, I think that amateur breeders might find it rewarding to work on the improvement of S. cardiophyllum itself. Even though the tubers are small, the species has many valuable traits and it might be possible to work on them more productively simply by breeding better varieties of S. cardiophyllum.

Subramanian (2017) found that at least some accessions of this species have unusually low potassium content.

Resistances

Vega (1995) found that this species is less frost tolerant than domesticated potato.

Some accessions of this species carry the Rpi-blb3 gene, conferring late blight resistance.

| Condition | Type | Level of Resistance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternaria solani (Early Blight) | Fungus | Resistant | Prasad 1980 |

| Alternaria solani (Early Blight) | Fungus | Somewhat resistant | Jansky 2008 |

| Globodera pallida (Pale Cyst Nematode) | Invertebrate | Not resistant | Bachmann-Pfabe 2019 |

| Globodera rostochiensis (Potato Cyst/Golden Nematode) | Invertebrate | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Colorado Potato Beetle) | Invertebrate | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Potato Aphid) | Invertebrate | Resistant | Alvarez 2006 |

| Meloidogyne spp. (Root Knot Nematode) | Invertebrate | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Myzus persicae (Green Peach Aphid) | Invertebrate | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Pectobacterium carotovorum (Blackleg/Soft Rot) | Bacteria | Somewhat resistant | Chung 2011 |

| Phytophthora infestans (Late Blight) | Fungus | Resistant | Gonzales 2002 |

| Phytophthora infestans (Late Blight) | Fungus | Somewhat resistant | Bachmann-Pfabe 2019 |

| Potato Virus Y (PVY) | Virus | Somewhat resistant | Cai 2011, Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Synchytrium endobioticum (Wart) | Fungus | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

Glykoalkaloid content

According to Johns (1990), S. cardiophyllum did not contain measurable amounts of solanine or chaconine, only a small amount of a glycoalkaloid tentatively identified as demissine. (I am not citing specific amounts, because at least some of the accessions of S. cardiophyllum included have since be reclassified as S. ehrenbergii and vice versa.) Some sources suggest that this species is not able to synthesize glycoalkaloids at all. Based on these report, S. cardiophyllum might serve a more digestible substitute for those who have difficulties with the common potato glycoalkaloids.

On the other hand, Sotelo (1998) found much higher and clearly unsafe TGA levels of 138.8 mg/100 g and 137.5 mg/100 g (solanine and chaconine combined and recalculated from dry to wet weight). S. cardiophyllum accessions will need to be carefully evaluated for safety, although any with levels as high as these should be terribly bitter and inedible.

Images

Cultivation

I have found this species about as easy to germinate as S. tuberosum under the same conditions.

Towill (1983) found that seeds of this species stored at 1 to 3 degrees C germinated at 84-94% after 25 years.

S. cardiophyllum is native to highland areas in Mexico. It is adapted to somewhat warmer and drier conditions than the Andean wild potatoes.

According to Villa Vasquez (2011), where S. cardiophyllum is farmed in Mexico, it is planted in November and June in tunnels or in open fields in July. The tubers are sown only 2.5 inches (5 cm) apart in rows about 20 inches (50 cm) apart. The average temperature during this period is about 72 degrees (23 C), reaching a maximum of about 90 (32 C). This is significantly earlier than the plants grow naturally and requires irrigation. The plants are forced to tuberize by withholding water. Harvest is about 3.5 pounds per square yard.

The flowering period of this species is relatively short – about 4 to 6 weeks.

This species typically has about five months of dormancy.

This species is listed as a noxious weed in California.

Breeding

While my own selections top out at about an inch in diameter, the USDA Potato Introduction Station has made some selections with tubers as long as 2 to 3 inches. This bodes well for cultivar development in this species.

Diploids of this species are sometimes self-compatible (Estrada-Luna 2002). Tetraploids are generally not self-compatible due to male sterility.

Crosses with S. tuberosum

| Female | Male | Berry Set |

Seed Set | Germ | Ploidy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cardiophyllum | S. tuberosum 4x | None | None | Jackson (1999) | ||

| S. tuberosum 4x | S. cardiophyllum | Minimal | None | Jackson (1999) |

Crosses with other species

Watanabe (1991) found that 7.8% of varieties of this species produced 2n pollen and Jackson (1999) found 1-16%, which would be effectively tetraploid and 2EBN.

| Female | Male | Berry Set |

Seed Set | Germ | Ploidy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

References

Solanum cardiophyllum at Solanaceae Source