Solanum commersonii

| Common Names | Commerson potato, Commerson’s nightshade, Papa Purgante |

| Code | cmm |

| Synonyms | S. acroleucum, S.compactum, S. henryi, S. mechonguense, S. mercedense, S. nicaraguense, S. ohrondii, S. rionegrinum, S. sorianum, S.tenue |

| Clade | Unknown |

| Series | Commersoniana |

| Ploidy | Diploid (2x), Triploid (3x) |

| EBN | 1 |

| Tuberization Photoperiod | Long Day |

| Self-compatibility | No |

| Nuclear Genome | Unknown |

| Cytoplasmic Genome | Unknown |

| Citation | Dunal: Encycl. suppl. 3:746. 1814 |

Description

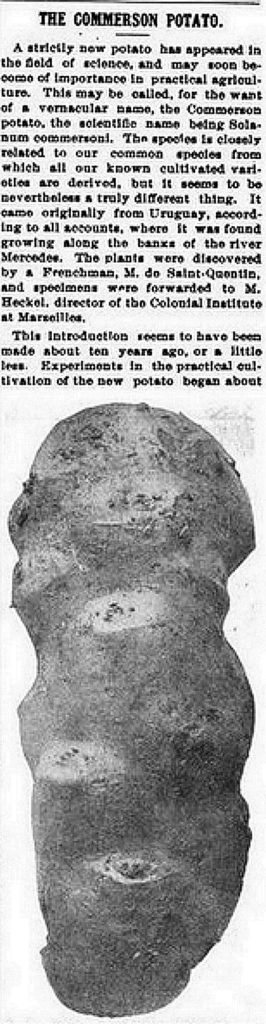

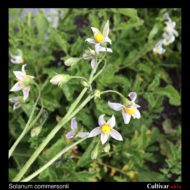

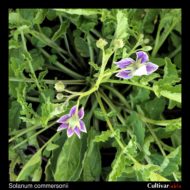

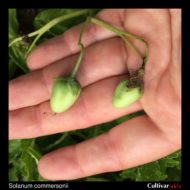

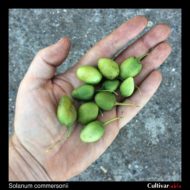

Solanum commersonii is a species of Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Brazil. Plants are low growing and often rosette like, with what I would describe as a “weedy” appearance. Flowers are small, stellate, white to purple, but usually more colorful on the back than the front. Berries are long and tapering. Tubers are usually small and while with moderately deep eyes, but tubers as large as 4.7 x 2.4 inches (12 x 6 cm) have been reported. According to Hawkes, this was the first wild potato species to be named and described and the first collected on a scientific expedition.

The specific epithet, commersonii, honors French naturalist Philibert Commerson, who collected the type specimen. While there is no completely standardized pronunciation for scientific names, the most common way to pronounce this species is probably so-LAY-num kah-mer-SOHN-ee-eye.

In its native range, S. commersonii is a widespread, weedy plant, growing in a variety of habitats from sea level to 1300 feet (400 m) (Hawkes 1969). It is noted to grow near to the sea, in rocky areas and dunes, which suggests some salt tolerance.

There are reports of this species being cultivated as an edible in France in the early twentieth century, where it produced “abundant, large, and palatable” tubers (Newman 1904). Reddick (1939) reported tubers of large, commercial size in an early evaluation of this species. A purple variety called ‘Violett’ appeared in European seed catalogs as early as 1908. According to Hawkes (1969), there may be reason for some skepticism about these claims, as S. tuberosum material was apparently mistaken for S. commersonii on more than one occasion.

S. commersonii is one of the few wild potato species for which the genome has been sequenced (Aversano 2015). Sequencing revealed that this species is dramatically less heterozygous than the domesticated potato (1.5% vs 53-59%). There are a number of possible reasons for this, including that the accession that was sequenced has been maintained in isolation and that the domesticated potato may have an unusual high level of heterozygosity as the result of modern breeding.

Resistances

This species can survive frosts down to 23 degrees F (-5 C) (Li 1977). Vega (1995) found that this species is more frost tolerant than domesticated potato and nearly as tolerant as S. acaule. Genomic analysis revealed that this species upregulates production of galactinol synthase, which has been associated in other species with the production of raffinose oligosaccharides that can protect against osmotic stress (for example, stresses caused by frost exposure) (Aversano 2015).

In a study of early blight resistance, Jansky (2008) found that S. commersonii was one of the top three most resistant species tested.

| Condition | Type | Level of Resistance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternaria solani (Early Blight) | Fungus | Somewhat resistant | Jansky 2008 |

| Frost | Abiotic | Resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Globodera pallida (Pale Cyst Nematode) | Invertebrate | Not resistant | Castelli 2003 |

| Globodera pallida (Pale Cyst Nematode) | Invertebrate | Not resistant | Bachmann-Pfabe 2019 |

| Globodera rostochiensis (Potato Cyst/Golden Nematode) | Invertebrate | Resistant | Castelli 2003 |

| Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Colorado Potato Beetle) | Invertebrate | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Meloidogyne spp. (Root Knot Nematode) | Invertebrate | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Pectobacterium carotovorum (Blackleg/Soft Rot) | Bacterium | Somewhat resistant | Chung 2011, Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Phytophthora infestans (Late Blight) | Fungus | Somewhat resistant | Gonzales 2002 |

| Phytophthora infestans (Late Blight) | Fungus | Somewhat resistant | Bachmann-Pfabe 2019 |

| Potato Virus X (PVX) | Virus | ||

| Potato Virus Y (PVY) | Virus | Not resistant | Cai 2011 |

| Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (White Mold) | Fungus | Resistant | Jansky 2006 |

| Streptomyces scabiei (Scab) | Bacterium | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Streptomyces scabiei (Scab) | Bacterium | Immune | Reddick 1939 |

| Synchytrium endobioticum (Wart) | Fungus | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) | Virus | ||

| Verticillium spp. (Verticillium Wilt) | Fungus |

Glykoalkaloid content

Carputo (2003) found a value of 48.1 mg / 100g for this species, a level more than double the safety limit, with three glycoalkaloids: dehydrodemissine, dehydrotomatine, and dehydrocommersine. Gregory (1981) found a TGA value of 23 mg/g dry weight, which should translate into roughly 230 mg / 100g fresh, a very high amount.

I have tasted a random sampling of tubers from seed grown plants of these species and found them all palatable. That seems like good luck, or perhaps some of the glycoalkaloids in this species are not as bitter as the more common solanine and chaconine. Most accounts report that the tubers are bitter and the Uruguayan name “papa purgante,” suggests that this is likely to be a defining characteristic of the species.

Images

Cultivation

Chen (1976) found that this species reaches its maximum frost resistance (about 11 degrees F, -11.7 C) following a three week period of shortening photoperiod and reducing day and night temperatures.

Bamberg (1995) found that at least some accessions of S. commersonii flower better at high temperatures than under typical temperate growing conditions. Flowering was better when greenhouse temperatures exceeded 100 degrees F for several hours during the day.

I have noticed that berries of this species are easily dislodged, even before they are mature. My normal practice is to give a little shake to each inflorescence and harvest any berries that fall off; with this species, even young berries tend to drop. It might be a good idea to tie up or otherwise support inflorescences and to shelter the plants from strong wind for greater yield. This species also produces many seedless, parthenocarpic berries, so seed yields can be surprisingly low.

Breeding

Watanabe (1991) found that 4.8% of varieties of this species produced 2n pollen and Jackson (1999) found 1-10%, which would be effectively tetraploid and 2EBN.

Crosses with S. tuberosum

| Female | Male | Berry Set |

Seed Set | Germ | Ploidy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. commersonii |

S. tuberosum 2x |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Emme 1937 | |

| S. commersonii | S. tuberosum 4x |

None | None | Jackson 1999 | ||

| S. commersonii 3x |

S. tuberosum 4x | Yes | Yes | Yes | Bukasov 1940 | |

| S. commersonii 3x | S. tuberosum 4x | Yes | Yes | Yes | Perlova 1945 | |

| S. tuberosum | S. commersonii | Minimal | None | Jackson 1999 |

Crosses with other species

Hawkes (1969) noted that, although their ranges overlap, there appear to be few wild hybrids between S. commersonii and S. chacoense.

| Female | Male | Berry Set |

Seed Set | Germ | Ploidy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. commersonii |

S. berthaultii (as S. tarijense) |

Yes | No | Hawkes 1969 | ||

| S. commersonii 3x | S. demissum | Yes | Yes | Yes | Reddick 1939, Black 1945 | |

| S. commersonii |

S. jamesii |

Yes | Yes | Reddick 1939 | ||

| S. commersonii | S. brevicaule (as S. spegazzini) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | von Olah 1938 | |

| S. commersonii | S. brevicaule (as S. spegazzini) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | 2x | Propach 1940 |

| S. commersonii |

S. chacoense |

Yes | Yes | Yes | 2x | Propach 1940 |

| S. commersonii |

S. chacoense |

No | Hawkes 1969 | |||

| S. commersonii 3x | S. x edinense |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Broili 1921 | |

| S. commersonii |

S. kurtzianum |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Perlova 1945 | |

| S. commersonii 3x | S. stoloniferum |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Vavilov 1938 | |

| S. commersonii 3x | S. stoloniferum | Yes | Yes | Yes | Emme 1937 | |

| S. commersonii | S. verrucosum | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2x | Propach 1940 |

| S. commersonii | S. wittmackii | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2x | Propach 1940 |

| S. commersonii |

S. stoloniferum (as S. fendleri) | Yes | Yes | Reddick 1939 | ||

| S. stoloniferum (as S. fendleri) | S. commersonii | Yes | Yes | Reddick 1939 |

References

Solanum commersonii at Solanaceae Source

1 thoughts on “Solanum commersonii”

Comments are closed.

I want to know what gene or genes are responsible for the tubers in these plants (potatoes and commerson’s nightshade).