Solanum curtilobum

| Common Names | Papa rucki, Choque pitu, Ocucuri |

| Code | cur |

| Synonyms | |

| Clade | 4 |

| Series | Tuberosa |

| Ploidy | Pentaploid (5x) |

| EBN | 4 |

| Tuberization Photoperiod | Short Day |

| Self-compatibility | Yes |

| Nuclear Genome | A |

| Cytoplasmic Genome | P |

| Citation | Juzepczuk & Bukasov: Trudy vsecouz. sezda genetike 3:609. 1929 |

Description

Solanum curtilobum is perhaps better included among the cultivated species than the wild, but as species that has two-fifths wild genetics, the dividing line isn’t entirely clear. This species is treated more like a wild species in breeding programs. Of the three frost-resistant hybrid species, this is the most similar to domesticated tetraploid potatoes and the easiest to breed with.

The specific epithet means “short lobed,” which refers to the shape of the leaves. It is formed from the Latin words “curtus,” for “short,” and “lobus,” for “lobe.” While there is no completely standardized pronunciation for scientific names, the most common way to pronounce this species is probably so-LAY-num kur-ti-LOH-bum.

This species is cultivated primarily in the highest elevations of the Andes, from northern Peru to southern Bolivia, where S. tuberosum group andigenum will not survive due to frost. None of the accounts of this species that I have found indicate that it has ever been found in Colombia, but the USDA lists three accessions from Colombia, which is a puzzle. Plants look similar to Andean tetraploids and grow quite large under short day conditions, with some plants producing vines as much as seven feet long, although most are closer to three feet. Tubers most commonly have blue skin and white flesh. They do not have the kind of diversity of form found in either parent species and are typically round to oval with shallow eyes. The flowers are usually blue. Berries are smaller than those of any of the ancestral species, which I find interesting. Typically, berries are about 1/2 in diameter at maturity. This may be due to lower seed counts. Some accessions of this species are high in glycoalkaloids and are only consumed after processing into the freeze-dried form known as chuño, but the accessions available in the USA are all non-bitter and edible fresh.

There are two proposed origins of S. curtilobum. The first case is hybridization between tetraploid S. tuberosum group andigenum and S. juzepczukii (Hawkes 1962), making its genetic composition 60% S. tuberosum and 40% S. acaule. The tuberosum parent is tetraploid and 4EBN, while S. juzepczukii is triploid and 2EBN. To cross successfully, S. juzepczukii must have provided an unreduced (2n) gamete, giving the combination of a 2x S. tuberosum gamete and a 3x S. juzepczukii gamete for a 5x (pentaploid) progeny. The second case is hybridization between triploid S. tuberosum group andigenum and S. acaule (Gavrilenko 2013). In that case, the triploid andigena would have acted as the female parent with a 2n ovule and S. acaule would have fertilized with normal haploid pollen. The second case seems less likely, simply because 2n ovules are produced in lower numbers than 2n pollen.

Although it has an odd ploidy, S. curtilobum is self-compatible and is able to cross with other 4EBN potato species. These crosses typically produce near-tetraploid aneuploids; that is, tetraploids with some extra chromosomes. If these aneuploids are back-crossed to the tetraploid parent or produce seed through self-pollination, they tend to lose the extra chromosomes over several generations.

S. curtilobum has not been synthesized by crossing the putative parent species. This might be because it is hard to get the required 2n gamete from S. juzepczukii or it could be an indication that the hypothesized parents are not correct.

Resistances

Vega (1995) found that this species is a little more frost tolerant than S. tuberosum.

All three accessions that we have grown here had strong frost resistance, surviving frosts undamaged that killed 99% of domesticated potatoes.

| Condition | Type | Level of Resistance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drought | Abiotic | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Frost | Abiotic | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Meloidogyne spp. (Root Knot Nematode) | Invertebrate | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Phytophthora infestans (Late Blight) | Fungus | Somewhat resistant | Bachmann-Pfabe 2019 |

| Potato Virus X (PVX) | Virus | Somewhat resistant | Machida-Hirano 2015 |

| Ralstonia solanacearum (Bacterial Wilt) | Bacterium | Some resistance | Martin 1977 |

Glykoalkaloid content

This species is generally used to make chuño or similarly processed potatoes, typically an indication of high glycoalkaloids. Osman (1978) found TGA levels ranging from 3.8 to 29.0 mg / 100 g for this species, levels that are not particularly high, but that do span the safety limit of 20 mg / 100 g.

The accessions available in the USA are mostly non-bitter, or barely bitter, probably safe enough to eat in moderate portions. In my experience, seed grown progeny of S. curtilobum segregate strongly for bitterness, with many plants that are more bitter than the parent variety.

The Aymara recognize two groups of potatoes according to palatability: Choque potatoes are not bitter and can be eaten fresh and Luki potatoes are bitter and must be processed before eating. Most varieties of S. curtilobum are in the Choque group.

Images

Cultivation

Plants are large and some tuberize under short days, so they need wide spacing. 15 inches (45 cm) is probably a good separation for this species.

This species is self compatible and will produce viable seed, but the seed does not produce true S. curtilobum (arguably). Instead, first generation seeds usually produce aneuploids between tetraploid and pentaploid. Subsequent self-pollinated generations converge toward tetraploidy. True S. curtilobum can only be propagated clonally. Perhaps “true” is not the right word. The seeds do not produce pentaploids, but I suppose that tetraploids of this species are still S. curtilobum.

Accessions Evaluated

The following accessions were examined to prepare this profile. I have evaluated 9/11 accessions currently available from the US Potato Genebank.

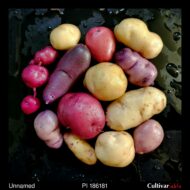

PI 186181

A true seed accession collected in Peru in 1950. This is the most strongly short day of the accessions that I have tried and will probably do best if grown well into the fall.

PI 195181

A clone of unknown origin collected in 1951. Chromosome count is 48, so this may not be S. curtilobum.

PI 225649

A true seed accession collected in 1951. Reportedly collected in Colombia, but it was probably just donated from the Colombian potato collection. Larger tubers, good long day tuberization, and interesting shapes and colors from this one.

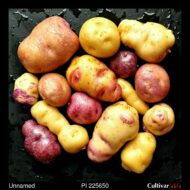

PI 225650

A true seed accession collected in 1951. Reportedly collected in Colombia, but it was probably just donated from the Colombian potato collection. A mix of long and short day tuberizers.

PI 225651

A true seed accession collected in 1951. Reportedly collected in Colombia, but it was probably just donated from the Colombian potato collection. Lots of long day tuberizers, good yields, and high tuber counts.

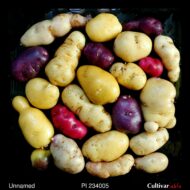

PI 234005

A true seed accession collected in Bolivia in 1956. A mix of long and short day tuberizers. Yields on the low side.

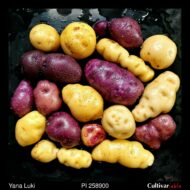

PI 258900 “Yana Luki”

A true seed accession collected in Potosi, Bolivia in 1949. Mostly long day tuberizers. High yields and high tuber counts.

PI 599282 “Waca Corota”

A clone collected in Potosí Bolivia before 1996.

PI 604206

A clone collected in Bolivia before 1993. Blue tubers. I offer this variety as “Blue Bolivian.” It was the highest summer yielding variety of the clones that I evaluated.

PI 604207 “Chiar Choque Pitu”

A clone collected in Bolivia before 1993. Blue tubers. Just shy of PI 604206 in yield and overall somewhat difficult to distinguish.

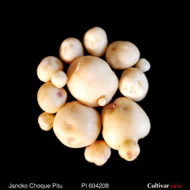

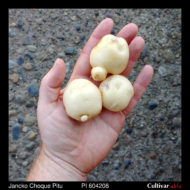

PI 604208 “Jancko Choque Pitu”

A clone collected in Bolivia before 1993. White tubers. Low yield compared to the other clonal accessions.

Breeding

I think it is kind of surprising that there hasn’t been more breeding done with S. curtilobum as a tetraploid. After a few generations of selfing or crossing between varieties, they stabilize at the tetraploid level. Pentaploid S. curtilobum has 3 copies of the andigenum genome and 2 copies of the acaule genome. During the process of tetraploid stabilization, it will lose one copy of the andigenum genome, so the tetraploid is 50% andigenum and 50% acaule. There ought to be plenty of interesting traits to explore in that mix.

S. curtilobum sets much less seed per berry than domesticated tetraploids and I would guess that this is because the uneven distribution of chromosomes doesn’t work out in a way that produces a viable seed much of the time. Seed set improves with each generation of outcrossing in my experience.

In the true pentaploid form, this species has 4EBN and it crosses readily with 4EBN domesticated tetraploids. It carries three copies of the domesticated potato genome from its tetraploid domesticated progenitors, which will have 1/2:1/2 EBN alleles, and two copies of the S. acaule genome from its wild parent. S. acaule is a tetraploid with 2EBN, which means that it must carry four copies of the genome that have 1/2:0 EBN alleles. Adding together the gametes, we would get 1/2:1/2+1/2:1/2+1/2:1/2+1/2:0+1/2:0, for a total of 4EBN. It is more interesting to speculate on the self-pollinated progeny of S. curtilobum. We should expect the progeny to gradually lose the extra, unpaired set of chromosomes, which I would expect to be one of 1/2:1/2 EBN carrying domesticated genomes. That means that, as the progeny shed chromosomes and stabilize toward tetraploidy, they would likely be 3EBN tetraploids. This may help to explain the poor seed set in this species.

Crosses with S. tuberosum

| Female | Male | Berry Set |

Seed Set | Germ | Ploidy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. curtilobum | S. tuberosum (4x) | High | Low | Yes | 4x+ | |

| S. tuberosum (4x) | S. curtilobum | Low | Low | Yes | 4x+ |

Crosses with other species

| Female | Male | Berry Set |

Seed Set | Germ | Ploidy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|