Solanum violaceimarmoratum

| Common Names | |

| Code | vio |

| Synonyms | S. multiflorum, S. urubambae, S. villuspetalum |

| Clade | 4 |

| Series | Conicibaccata |

| Ploidy | Diploid (2x) |

| EBN | 2 |

| Tuberization Photoperiod | Unknown |

| Self-compatibility | No |

| Nuclear Genome | A |

| Cytoplasmic Genome | Unknown |

| Citation | Bitter: Repert. Spec. Nov. Regni Veg. 11: 389. 1912. |

Description

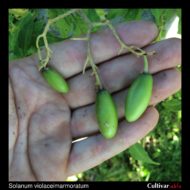

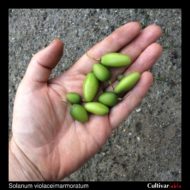

Solanum violaceimarmoratum is native to the eastern slopes of the Bolivian Andes, at elevations of roughly 6500 to 11200 feet. An unusual species, thought not to be closely related to other wild potatoes. Very tall plants, reaching nine feet in height. Stolons three feet or more. Tubers reaching two to three inches in length, more in cultivation. Some sources report that the tubers are moniliform, but I haven’t observed this. Tuber skin ranges from white to purple and flesh color white to light yellow. Tubers become dark purple with exposure to light. Purple flowers. Berries conical.

The specific epithet, violaceimarmoratum, means “purple mottled” and probably refers to the stems. It is formed from the Latin words “violaceus,” for “violet,” and “immarmoratus,” for “marbled.” While there is no completely standardized pronunciation for scientific names, the most common way to pronounce this species is probably so-LAY-num vie-oh-lay-see-mar-moh-RAH-tum.

This species can survive frosts down to 27 degrees F (-3 C) (Li 1977), about the same as the domesticated potato. Even though it grows at relatively high elevations, It has poor frost resistance compared to most wild potatoes, most likely because the eastern slopes of the Andes to which it is native are warmed by updrafts from the Amazon basin (Smillie 1983). It grows in sandy clay soils, developing best in loose, moist soils with high organic matter (Patiño 2008).

Subramanian (2017) found that at least some accessions of this species have unusually high potassium content.

This species has been tentatively classified as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List (Cadima 2014).

| Condition | Type | Level of Resistance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alfalfa Mosaic Virus (AMV) | Virus | Resistant | Horvath 1989 |

| Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV) | Virus | Resistant | Horvath 1989 |

| Frost | Abiotic | Not resistant | Li 1977, Smillie 1983 |

| Globodera pallida (Pale Cyst Nematode) | Invertebrate | Not resistant | Castelli 2003 |

| Globodera rostochiensis (Potato Cyst/Golden Nematode) | Invertebrate | Resistant | Nagaich 1980 |

| Globodera rostochiensis (Potato Cyst/Golden Nematode) | Invertebrate | Not resistant | Castelli 2003 |

| Pectobacterium carotovorum (Blackleg/Soft Rot) | Bacteria | Somewhat resistant | Chung 2011 |

| Phytophthora infestans (Late Blight) | Fungus | Resistant | Gonzales 2002 |

| Potato Virus X (PVX) | Virus | Resistant | Horvath 1989 |

| Potato Virus Y (PVY) | Virus | Not resistant | Cai 2011 |

| Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (White Mold) | Fungus | Resistant | Jansky 2006 |

Glykoalkaloid content

I have found no published information about glycoalkaloids in this species. I have tasted the tubers of some seedlings and found most of them palatable, while some produce a slight sour sensation at the back of the mouth.

Images

Cultivation

I have found seeds of this species slow and difficult to germinate using the standard conditions for S. tuberosum. Overall, I was surprised by how happy and healthy this species seems to be in our climate. Plants grow very large and persist late into the year in excellent condition. In 2018, a plant that was surrounded by other potato species that were infected with late blight showed no symptoms at all. I kept that clone for further investigation and plan to attempt crosses with domesticated diploids.

Towill (1983) found that seeds of this species stored at 1 to 3 degrees C germinated at 70% after 10 years.

Tubers have at least four months of dormancy.

Trapero-Mozos (2018) determined that this species will tolerate a temperature of 40 C after acclimation for a period of time at 25 C.

Breeding

Crosses with S. tuberosum

I have found that S. violaceimarmoratum crosses easily with diploid S. tuberosum.

Watanabe (1991) found that 2.8% of varieties of this species produced 2n pollen, which would be effectively tetraploid and 4EBN.

| Female | Male | Berry Set |

Seed Set | Ploidy | Germ | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. violaceimarmoratum | S. tuberosum | None | None | Jackson (1999) | ||

Crosses with other species

| Female | Male | Berry Set |

Seed Set | Ploidy | Germ | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. violaceimarmoratum | S. stipuloideum (as S. circaefolium and var. capsibaccatum and var circaefolium) | Low | Very Low | Yes | Ochoa 2004 | |

| S. stipuloideum (as S. circaefolium and var. capsibaccatum and var circaefolium) | S. violaceimarmoratum | Low | None | Ochoa 2004 | ||

| S. violaceimarmoratum | S. commersonii | No | No | Ochoa 2004 | ||

| S. commersonii | S. violaceimarmoratum | No | No | Ochoa 2004 | ||

| S. violaceaimarmoratum | S. laxissimum | High | High | Yes | Ochoa 2004 | |

| S. laxissimum | S. violaceaimarmoratum | High | High | Ochoa 2004 | ||

| S. violaceaimarmoratum | S. limbaniense | High | High | Yes | Ochoa 2004 | |

| S. limbaniense | S. violaceaimarmoratum | High | High | Ochoa 2004 | ||

| S. violaceaimarmoratum | S. rhomboideilanceolatum | High | High | Yes | Ochoa 2004 | |

| S. rhomboideilanceolatum | S. violaceaimarmoratum | High | High | Ochoa 2004 | ||

| S. violaceaimarmoratum | S. chomatophilum | No | No | Ochoa 2004 | ||

| S. chomatophilum | S. violaceaimarmoratum | No | No | Ochoa 2004 | ||

| S. violaceaimarmoratum | S. humectophilum | None | None | Ochoa 2004 | ||

| S. humectophilum | S. violaceaimarmoratum | Low | Low | Ochoa 2004 |